From New York to New Delhi, a hugely influential print tradition of hunk and gay erotica is finally seeing the light

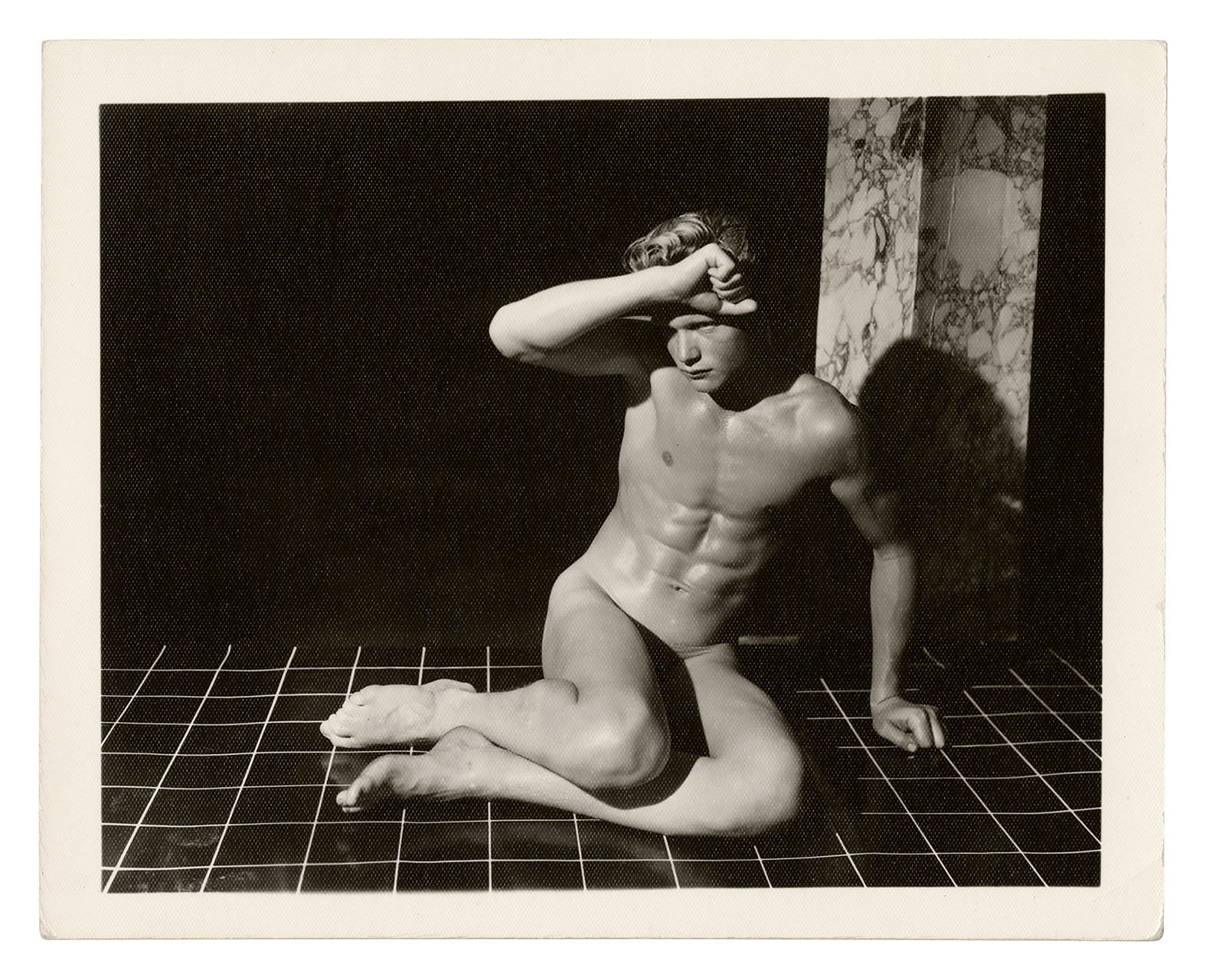

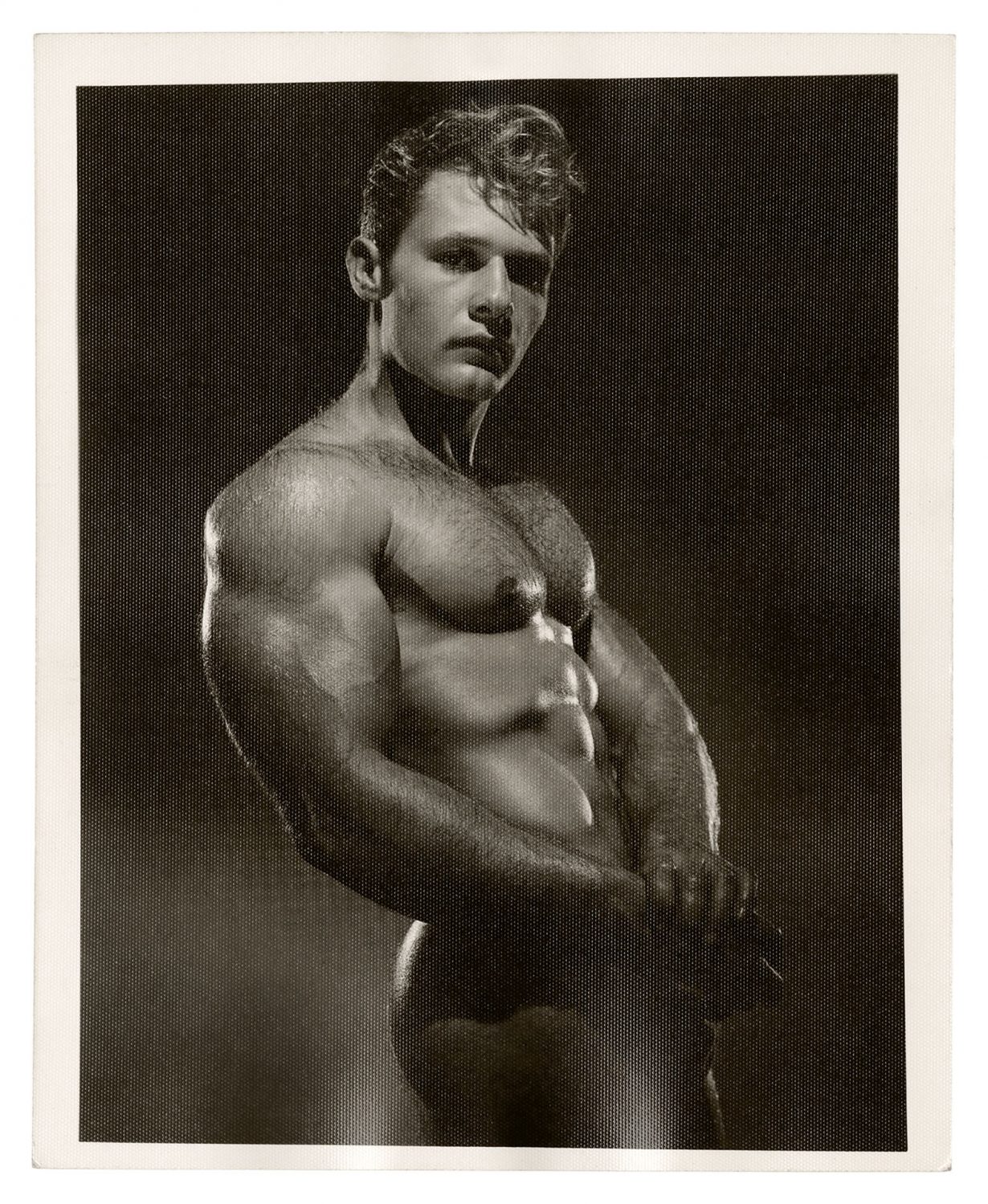

Visual representations of gay sexual desire have long been pushed underground and suppressed. Yet it is often from the margins that communities can come together and express a shared identity, often hidden in plain sight. In the early 1950s, writer and curator Vince Aletti came upon a photograph in a magazine of two near-naked teenagers, one slung over the other’s shoulder. Aletti was eight years old. It was this early encounter with imagery imbued with a latent homoeroticism that shaped the trajectory of his later work as a prolific collector of printed materials, in particular his acquisition of stacks of American physique magazines from the late 1930s to the late 60s. These were published by photographers like Bob Mizer who had realised the pangs of gay desire stirred by mainstream muscle mags and men’s health publications featuring so-called hunks, and began publishing their own iterations of magazines explicitly intended for queer consumption, filling them with studio photographs of ripped and mostly nude men. Images from Aletti’s collection have now been brought together in Physique, a weighty compendium that sheds light on the prohibitions and covert desires of the pre-Stonewall era America, as well as the many creative means of evading censorship.

On the other side of the world, meanwhile, India saw a similar phenomenon in the proliferation of printed materials during the 1980s and 90s. Here too, gay men would find themselves surrounded by swathes of heterosexual advertising and glossy publications like Cosmopolitan and Debonair glorifying the male form, while longing for something that ventured beyond the mainstream. It was publications like Bombay Dost, India’s first LGBTQ magazine, that were able to direct readers to organisations like Counsel Club, the first support group for gay men in India, founded in Calcutta. Started in August 1993, Counsel Club invited letters via a post-box number and discreetly conducted one-on-one advice sessions in the city’s parks and cafes. The club’s own house journal Pravartak was started on the self-initiative of twenty-three-year-old Pawan Dhall, who wanted to keep the conversation about being gay and living with HIV alive in Calcutta. They were typed in the dead of the night and stapled,” Dhall tells me. “I was inspired by how friends would bring out a newspaper when we were in school, and distribute it among friends and family.”

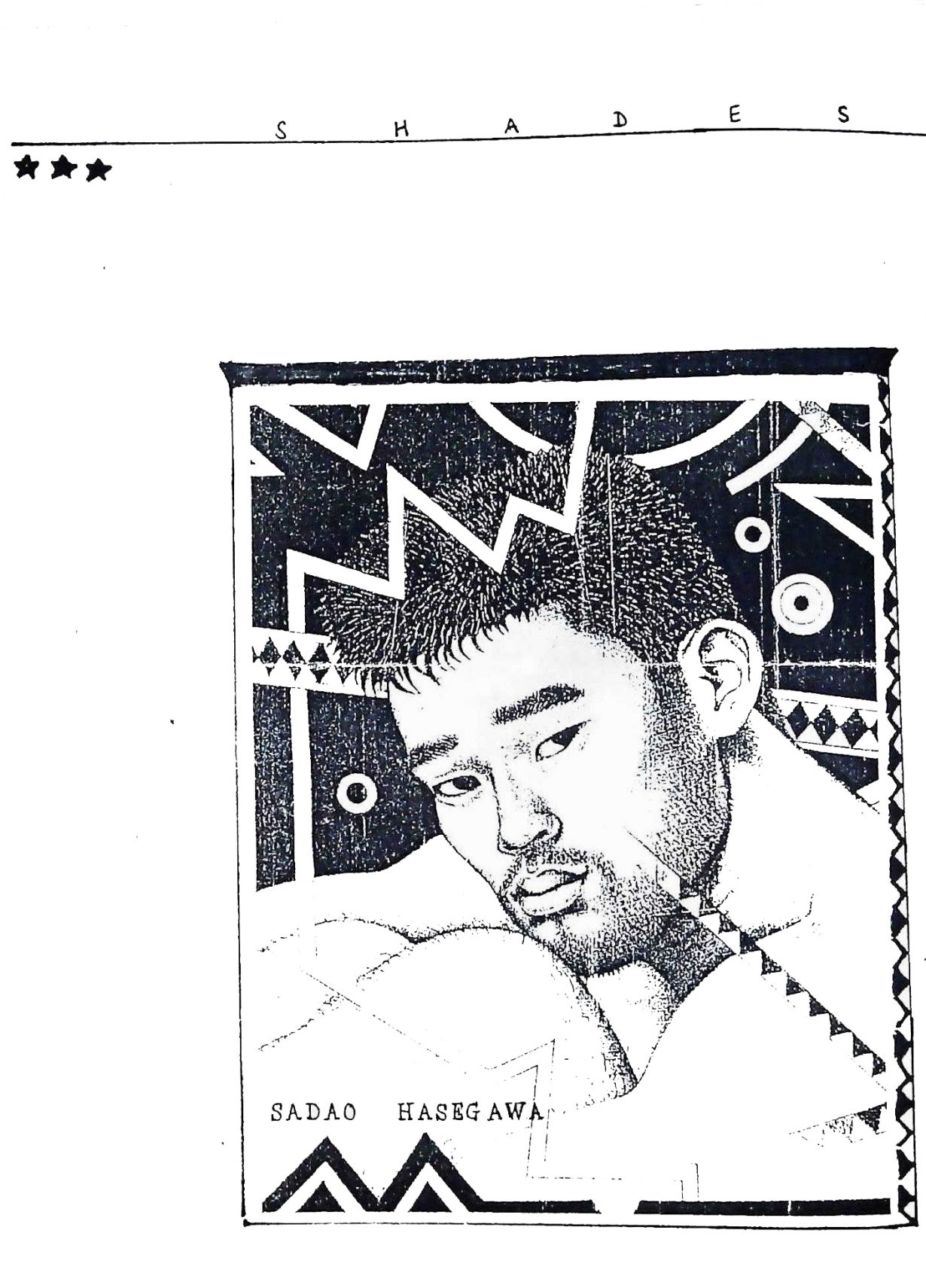

The popular appeal of mainstream photographs of musclemen, seemingly within both the straight and gay communities, drove a brisk business for American photography studios who worked with beefcake models for sports and explicitly LGBTQ publications alike, producing many of the images collected by Aletti. While in Calcutta, Pravartak frequently reprinted queer-coded illustrations from national newspapers. Its first issue carried a full-page print by Japanese graphic artist Sadao Hasegawa of a hunk, his eyelids heavy with desire. The magazine invited often invited readers to write in, with the resulting ‘animated enquiries’ (including queries on everything from access to spaces for having sex to personal outpourings of grief and loneliness) offering “a microcosm of an India that was sexually active, liberal, inquisitive, orthodox and repressed,” Pawan tells me. Imitating the heterosexual marriage Classified column in dailies, Pravartak offered their own take on the ‘Classified’ column, typically employed in a heterosexual marriage context, facilitating new means for those in the local gay community to meet each other. ‘Desperately seeks hunky middle-aged fellas for fun friendship’, wrote an unidentified twenty-year-old in Pravartak.

It was through forums such as these that gay men could begin to understand their sexual preferences as a form of political identity in the face of repression and, importantly, a space for community and solidarity. “People used Pravartak to come out, strategically leaving a copy of the publication or Bombay Dost in their room for their mother or father to see,” Pawan says. As Canadian critic Thomas Waugh writes in Hard to Imagine: Gay Male erotica in Photography and Film from their Beginning to Stonewall (1996), it was photochemical media and printed ephemera that enabled many in the gay community to grow up feeling less alone with their sexuality. Yet the circulation of such material also placed both publishers and readers, as well as organisers of community and activist groups for whom the circulation of printed material was crucial to their communications, at risk of police scrutiny. In 2001, members of the New Delhi-based NAZ Foundation for HIV/AIDS prevention work were accused under Section 292 for the sale of obscene books, and subsequently jailed for 47 days.

Domestic printers were often preferable for keeping production within the intimate confines of the home, but their rougher print quality also helped to minimise the risk of models being recognised. “There was always a fear of being outed because of Pravartak’s existence,” Pawan recalls. Rather than using the mail order system, “people would write to us saying don’t send us copies, we’ll collect it personally or send you a separate address.” While in the US, the landmark Manual Enterprises, Inc. Vs Day judgement of 1962 – notable for ruling that photographs of nude men are not obscene – paved the way for the broad circulation of male pornographic magazines without fear of legal repercussions.

It wasn’t until 2018 that the Supreme Court of India finally successfully challenged Section 377 – a British colonial Penal Code first introduced in 1860 that criminalised all homosexual activity alongside oral and anal sex as ‘unnatural intercourse’ – and ruled that the application of the law to consensual homosexual sex between adults was unconstitutional, ‘irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary’. During the decades when India’s gay community was criminalised, and as HIV spread rapidly across the country, the state was forced to depend on grassroots community groups like Counsel Club to spread awareness to gay men about practicing safe sex and giving them condoms, while simultaneously forcing them to the margins. Through no choice of their own, these periodicals and organisations found themselves operating as activist groups from the very beginning. Such public health messaging was also in operation in American physique magazines like Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial, which carried commentary on sexual health or political issues like civil rights alongside hunky photographs and carefully-coded editorial content on sex.

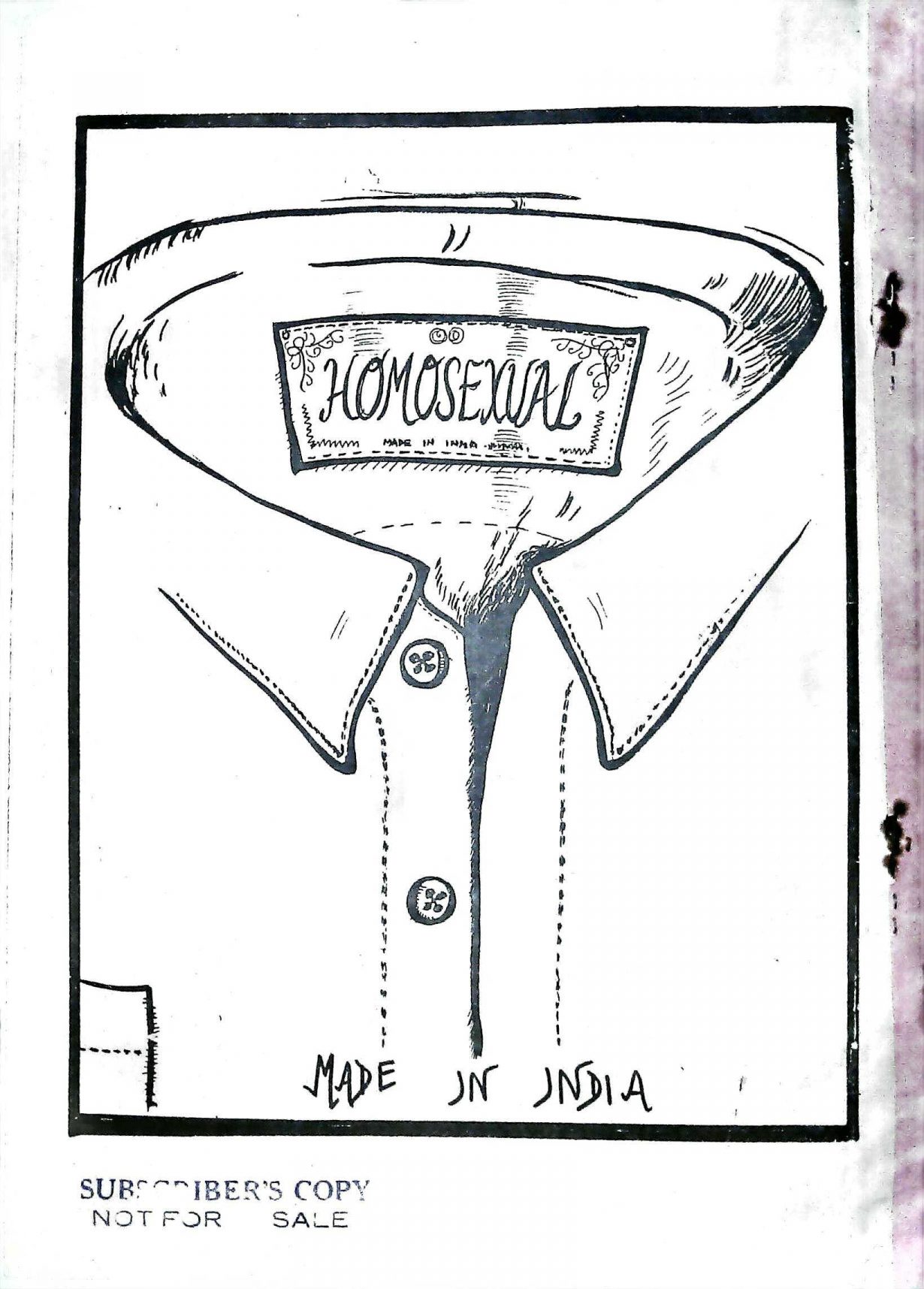

Former HIV and human rights adviser at the British Council in India, Veena Lakhumalani, who was closely involved with the formation of Counsel Club during the 1990s, recalls the blatant denial of the West Bengal police over the state’s gay population, going so far as to claim that Bengalis could never be gay. It was the nation state’s obsession with promoting indigenous identity as inherently heterosexual (and decrying anything that deviated from this as foreign) that led to a sketch of a men’s shirt in Issue 3 of Pravartak; the brand label reads ‘Homosexual’, while below it is sewn ‘Made in India’. It is a phrase that takes on newly charged dimensions just three decades later, used by the right-wing Narendra Modi government to promote indigenous industries, all the while hounding religious and sexual minorities. In 2023, the Supreme Court declined to legally recognise same-sex marriage, stating that it was a decision to be made by Parliament, which now makes it seem like an unachievable dream. Like the men writing in to Pravartak in search of a partner, the depiction of the homoerotic male form by studio photographers, whether in the US or elsewhere, reflects that same dream of a shared life spent neither hidden in the shadows nor on the activist frontlines fighting for representation. It is visually represented in images of a lover lounging on the sofa reading a newspaper, or demonstrating the ability to buy a portable television set for their shared home. Not a fantasy but something altogether more real, and more ordinary: momentarily imagining the possibilities of the personal beyond the political.

Upasana Das is a freelance writer with bylines in Vogue India, the New York Times and Dazed