Stephanie Syjuco’s book asks a simple question: ‘How do you talk back to the archive?’

Consider the lie embedded in a century-old photograph. Four Filipino men, dressed in ‘tribal’ costumes with spears in hand, pose for a portrait in front of a straw hut. They were among 1,200 people brought to the United States for the racist spectacle of the Philippine Village at the 1904 St Louis World’s Fair – meant to entertain and educate its American audience. The dehumanising display, and its photographic record, helped incorporate the newly acquired territory of the Philippines into an expanding imperial vision.

Manila-born, Oakland-based artist Stephanie Syjuco encountered the photographs of Philippine Village in 2019, while trawling the collections of the Missouri Historical Society and St Louis Public Library. The Unruly Archive brings together Syjuco’s work with archival collections in the United States from the last half decade, which scrutinises the ways in which they have systematically excluded and misinterpreted the history of the Philippines, and asks a simple question: ‘What does it mean to not see yourself clearly?’

Through digital and physical interventions, Syjuco disrupts the colonial archive’s asymmetrical history. In her series Block Out the Sun (2019), which draws from the World’s Fair archive, the four men reappear, this time obfuscated by the artist’s hands, which cover most of the staged scene, particularly their faces. Syjuco’s intervention both shows and doesn’t show, turning our attention away from the archival image and towards what the viewer might bring to it. ‘I do not make work about Filipino identity,’ she writes. ‘I make work about the white gaze.’

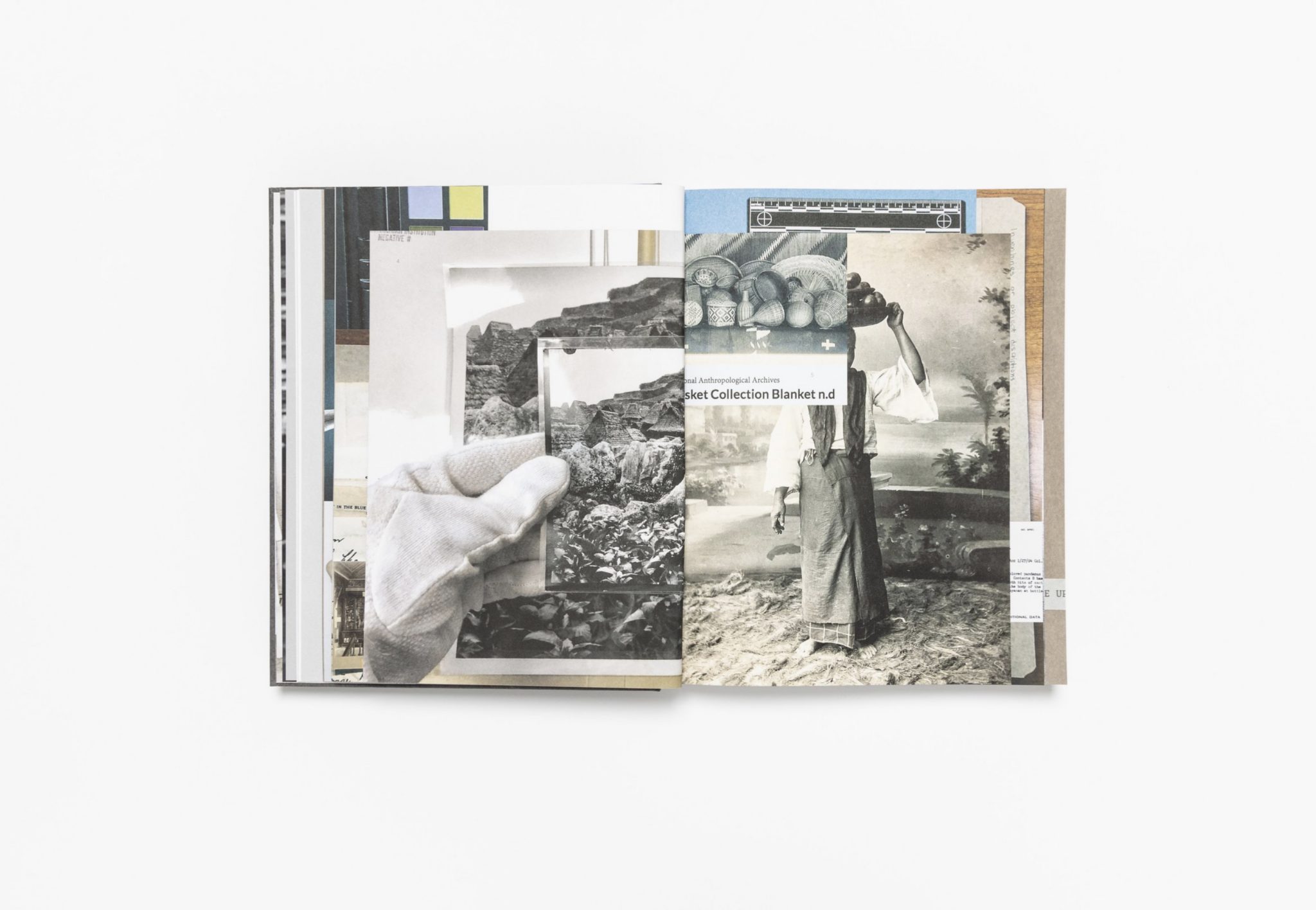

Across more than 300 pages that alternate between archival images and text contributions, The Unruly Archive braids content and form. Pages are cut unevenly, images are often deliberately cropped, outsized and low-resolution to mimic the unruliness and overabundance of archival research, with the original unabbreviated captions reproduced alongside. In this sense, the book simulates a search; ‘a type of forensics’, as Syjuco writes. It deploys the visual aesthetic of its source archives to critique what was or was not permitted into their historical record, and by whom.

An exemplar of this investigative approach is seen early on in the book. A series of three collages, titled Pileups (2021), engage with the collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in Washington, DC. Each work appears first in full and then deconstructed over subsequent pages with various elements – portraits of unnamed Filipinos, photographs of guns and cultural artefacts, botanical imagery – singled out, resized and captioned. Underscoring the layered and often visually overwhelming nature of these materials, Syjuco’s ‘unruly’ approach attempts to undermine the colonial archive’s relationship to precise and governable data. Her strategic cluttering reinstates a sense of complexity against the Smithsonian archive’s flatness.

For a book that deals with so much from the past, The Unruly Archive casts an equally sharp eye to the future. Among its most resonant tactics is the space given to other artists working with archives. Syjuco invites them to meditate on another simple question: ‘How do you talk back to the archive?’ Among the responders, Wendy Red Star reckons with her Apsáalooke inheritance and the museumification of Native material histories; Minne Atairu imagines an alternate history for the looted Benin Bronzes using artificial intelligence; L. J. Roberts exhumes forgotten Stonewall revolutionaries from the microfiche archives of the New York Public Library; and Gelare Khoshgozaran positions talking back as ‘a response to the archive as a location of power’. The Unruly Archive remains animated by a larger faith in the value of looking back, carefully and historically. Syjuco considers archives as places of both violence and power, while reminding us of the contingency of their construction. In searching for her own cultural identity within these collections, she finds a system that wasn’t built to see her fully at all. As a response, the artist reclaims these materials from their institutional coffers – both with attention to the past and in service of future readers. ‘Forwards through the archive,’ Syjuco reminds us, ‘not backwards’.

The Unruly Archive by Stephanie Syjuco. Radius Books, $65/ £51 (hardcover)