The much-hyped novelist’s latest work, which stars two art critics, is a jumbled mess

A novel that seemingly tries to be subversive for the sake of it, Sheila Heti’s Pure Colour is a philosophical fable without a philosophy, a glossy and depthless rumination on mysticism, a narrative that has cast aside the shackles of realist literary convention but also engagement. It’s one of the worst books I’ve read in some time, and though hyperbolic, there’s plenty more overwrought statements to be found in the novel.

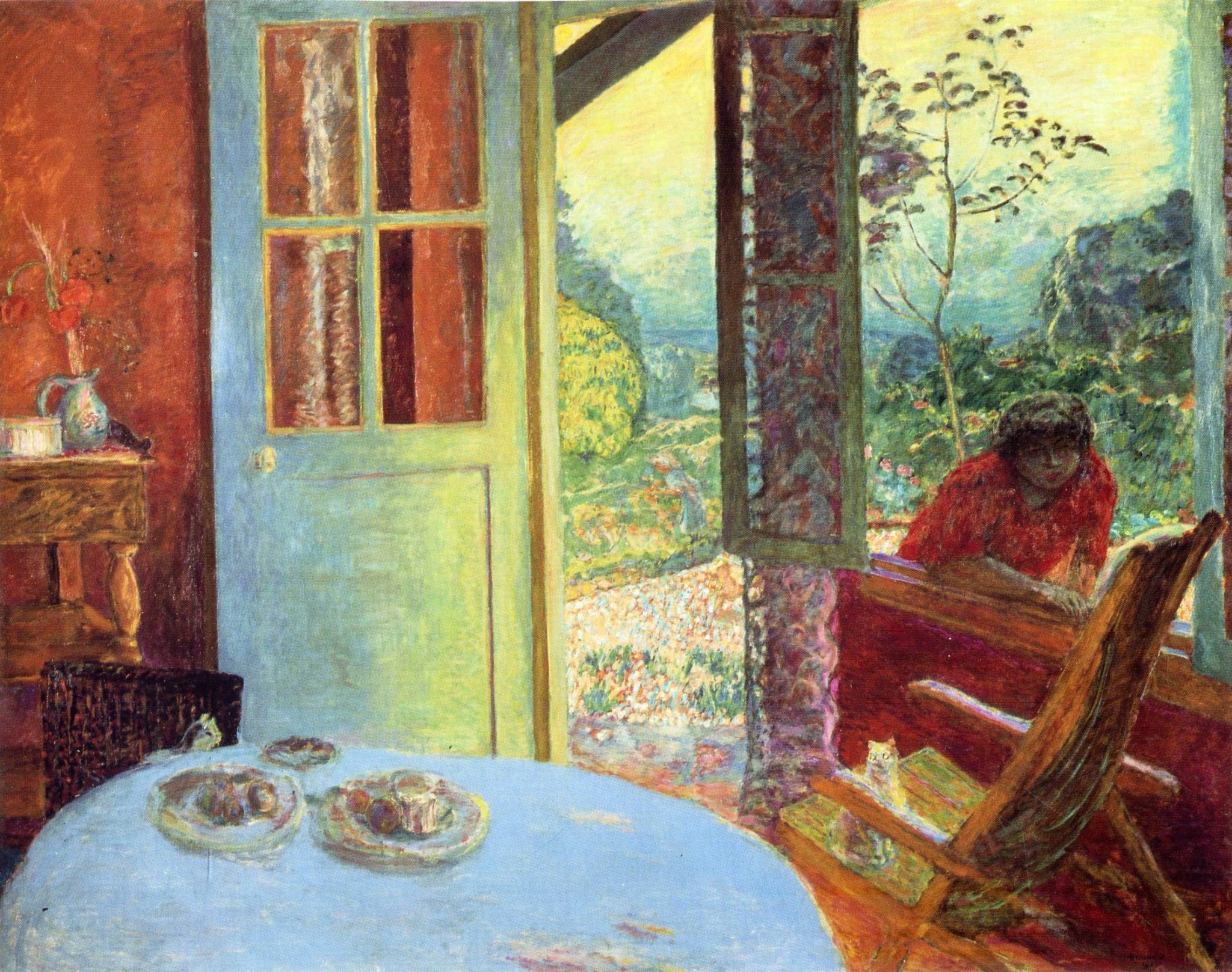

Titled after the documentary In Search of Pure Colour: Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) (1984), Heti’s book takes inspiration from the painter’s permeable, unfinished compositions in various ways. Its conceptual premise is that God, an artist, is tired of the first draft of the world and is looking towards the second – a transition facilitated by the incoming ecological apocalypse. This also conveniently posits Pure Colour as a fragmentary first draft, a construction too fragile for the overtly judgmental critics of the Twitter age that it rails against, instead situating its narrative in some fabular, preinternet Toronto. Its protagonist, Mira, her love interest, Annie, and her dying father are all flat characters allegorised according to bird, bear and fish personality types. Mira and Annie are aspiring art critics who both attend the American Academy of American Critics, yet are fated to diverge from each other due to the fact that Mira is a bird obsessed with beauty (shining lamps and jewels, just as Bonnard is with luminous interiors), and Annie is a fish obsessed with collectivity. Art and art criticism in the novel loosely signify faith of sorts: bird, bear or fish types are also art critics – Platonic-style vessels through which a truth about God may be revealed.

As Mira’s grief at her father’s eventual death unfolds, she becomes mystically transfigured into a leaf, a form she is stuck in for some time. If this sounds rambling, that’s because it is – shifting continually between an omniscient first-person narrator musing about the contemporary fallen world, a stark third person revolving around Mira, and a collective ‘We’. Through these various admixtures of points-of-view, Pure Colour gradually gestures towards an ill-defined cosmology that could generously be read as performatively rerevising itself as it unfolds, or ungenerously as a kind of late-night rant in a bar. If mystical experience in essence is beyond language, then perhaps Heti’s style is trying to point to this abstraction, but what comes across is more a jumble of mysticism-lite: the transmigration of souls, the presence of the divine in the mundane, divine birth, and union with the divine all fly around like untethered thematic kites, showing their positive green sides while their darker obverses are ignored. No theodicy or cosmodicy here – unlike, for example, in For The Time Being (1999), Annie Dillard’s mystical reckonings with the nature of evil and suffering, or more contemporarily, the complexity found in Olga Tokarczuk’s recent The Books of Jacob (2021).

Pure Colour is staged as a more impersonal drama than the autofictive style Heti has been associated with, as in her previously lauded Motherhood (2018). I don’t think we’re meant to care for its allegorised, flat characters, but neither then do we care for its spiritual questions, which at times read like aphoristic Instagram posts, and are presented in a dialogic style that I can only describe as extremely online. Which is ironic – given the novel’s turn away from the internet – but I think its central preoccupation is what the right kind of connectivity might be, rather than metaphysics. In vaguely exploring this, the thinness or first-draftness of Pure Colour’s contents and style shuts out any connection to the reader – can this really be merited as a conceptual breakthrough? Writing that imparts knowledge formulates what it knows by letting its problems drift into our somatic registers of experience, through the sensorial and affective. Heti does not do this: we finish empty and unmoved – or in this case, unenlightened.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti, Harvill Secker, £16.99 (hardcover)