We live in the era of sad men going full throttle

If you’re planning on releasing a film soaked in gritty yet sentimental nostalgia, helmed by a violent yet vulnerable man locked in battle with powerful, seemingly unbeatable outside forces, yet also with his inner demons, while also trying to woo a woman way out of his league, then you’d better make sure it has at least one motorbike scene in it. Preferably a handful, at breakneck speed.

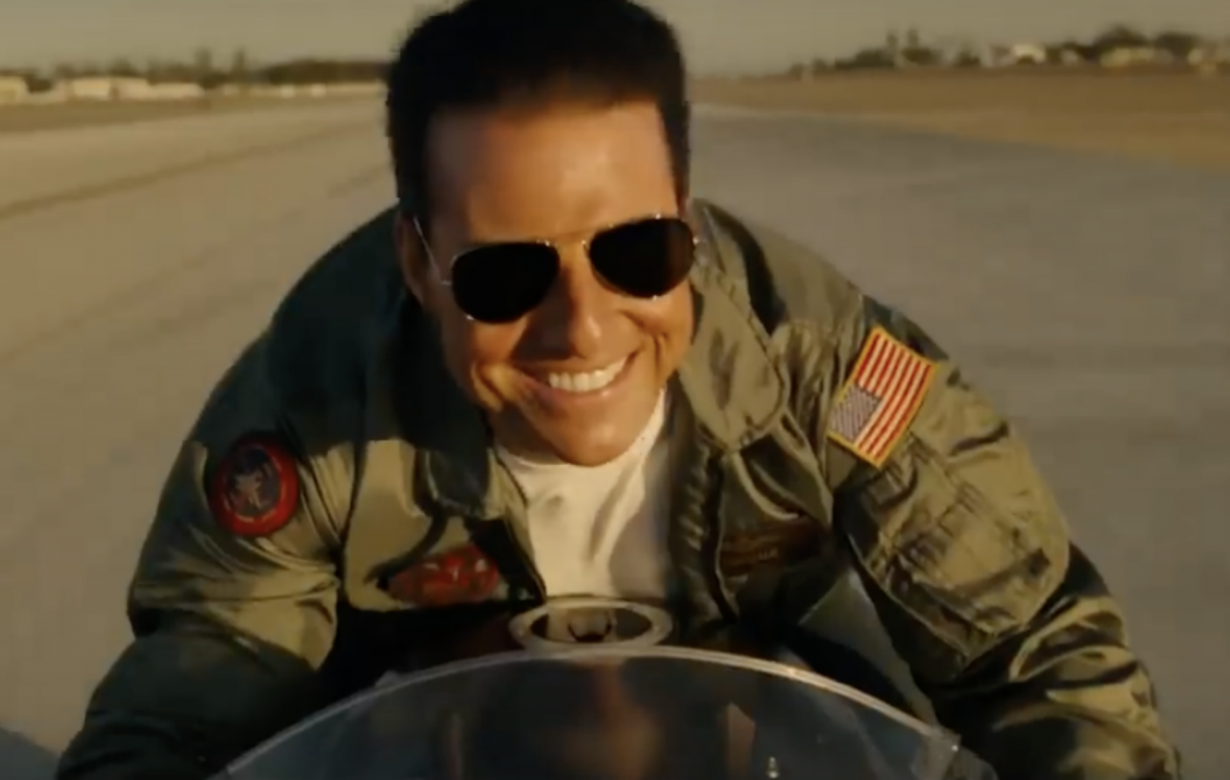

Motorbikes are having a moment. Late last year there was Daniel Craig’s gritty yet vulnerable Bond making an impossibly massive leap up a hillside to land unscathed in an Italian market square in No Time to Die (2021). Then there was Keanu Reeves’s spiritually enfeebled Neo catching a ride with Carrie-Anne Moss’s perpetually-badass Trinity in The Matrix Resurrections (2021). There was Robert Pattinson’s emo Bruce Wayne chasing Zoë Kravitz’s tail (The Batman, 2022). And now, there’s the speed-freak to beat them all: Tom Cruise’s Maverick is back in the saddle, occasionally with Jennifer Connelly along for the ride as a smoking-hot single mom. Let the lesson be learned: if you’re a flawed hard man with a barely-concealed tender heart, you’d better grab your leathers. This is the era of sad men going full throttle.

I know what you’re thinking. Maverick is cocky and back in the cockpit. Why are you making this about sadness and motorbikes when Top Gun is about sweaty men driving much bigger, faster, and more powerful machines? Well, aside from the fact that the 1986 Top Gun scene in which Maverick races his motorbike against a fighter jet along a runway like a one-man Kawasaki commercial has become so iconic that any call-back bike moment in Top Gun: Maverick (2022) is inevitably coated with nostalgia’s comforting gloss, it’s important because the motorbike scenes reveal what these big budget sequels and reboots really are. Midlife crisis movies.

Maybe the fact I included Robert Pattinson’s Batman is throwing you off here. It’s true that he’s a babe in arms compared to the other ageing action men of this cohort – the Nirvana-listening, guyliner-wearing, bat-cave-dwelling chiselled teenage upstart to Craig, Reeves and Cruise’s world-weary fifty-somethings. But even this proves my point because we all know Bruce Wayne is old really. We’ve seen him decade in, decade out, reboot upon reboot, donning his cape from roughly his 30s to his late 40s, then disappearing for a bit before being traded in for a younger model. As with Bond, Batman’s previous incarnations linger in the public consciousness and on the red carpet, always still in some sense Batman, always ageing. This year, Christian Bale is 48, Ben Affleck is 49, George Clooney (god bless his Batman) is 61, Val Kilmer is 62 and Michael Keaton is 70. All of their versions hang around Pattinson like shadows. And so, we watch Bruce again, in his late 20s to early 30s, acting like an angsty teenager – acting every bit the youngster someone older might look at with a mix of wistful fondness and vague scorn – in the full knowledge of what comes next. He’ll fight and fight to save the world and he’ll get old, and, despite all those fights, everything will be the same again. And then he’ll be young again; invented anew so he can do all the same things all over again.

Of course, all remakes and reboots are supposed to invent things anew, while also keeping them fundamentally the same. But this recent clutch of seemingly-incessant sequels – these midlife crisis movies – spin on a particular kind of reinvention: a familiar, virile, hyper-masculine hero-character softened around the edges. A dream of youth from a faraway perspective; a nostalgia that is also haunting.

Look closer at this old-new/new-old Maverick. He’s in his fifties, and suddenly he’s aware of mortality. Except it’s not his own he’s really worried about. Indeed, as the opening scene which sees the rule-bending, over-confident captain proving he can hit 10 times the speed of sound in an unauthorised test run suggests, Maverick-rebooted often appears so keen to put himself in harm’s way that at times his death drive seems to rival that of Daniel Craig’s Bond. Instead, the mortality he’s concerned with is that of the young naval pilots he now finds in his charge; whose lives he finds in his hands.

Many scenes in Top Gun: Maverick are call-backs to the 1986 original. The movie opens with aircrafts taking off, back-lit by the sun, as the instantly familiar notes of ‘Danger Zone’ kick in. The narcissistic navy warriors’ impossible abs glisten as they strain for balls on the beach (homoerotic volleyball updated to homoerotic football). A raucous bar scene ends with a rousing rendition of ‘Great Balls of Fire,’ only this time it’s not Goose on the keys but his son, Rooster (Miles Teller). Yet the most interesting moment of near-mirroring is the scene that follows, when Maverick is formally introduced to his new students. In the same way Maverick cringed in 1986 at the realisation he barged into the ladies’ loos to proposition his instructor, now Hangman and Rooster cringe at their realisation that they chucked their instructor out of a bar, after rinsing ‘pops’ for free drinks.

Now it’s Maverick’s turn to be undervalued, not recognised as a source of knowledge and authority – and, of course, not because of his gender, but his age. It’s a moment that cuts to the heart of the film, and its obsession with ageing, power, and seniority. 1986’s Maverick needed to get to grips with treating women like people and become less of a dick, and now, the new film says, it’s the new-gen Top Gun pilots that need to learn a bit of respect. The old dog knows his way around a dogfight. It’s the young bucks that need to learn new tricks.

Obviously, what any responsible lefty should be talking about when considering Top Gun is military propaganda, American imperialism, the glorification of war, et cetera. It would surely be remiss not to mention that, at the time of the original Top Gun’s release, the US navy had recruitment booths in theatres to attract riled-up punters. The tactic worked: in the year after its release, naval aviation saw a 500 percent boost to recruitment interest.

But, as this suggests, to talk about these things is to talk about machismo. Top Gun once was all about the arrogance of youth – alpha male strutting and competition that look a lot like a sexual display to anyone watching from the outside. Top Gun: Maverick is still about youth, but seen at a distance. As Rooster sings ‘Great Balls of Fire’, Maverick stands outside, looking in. He’s haunted by the memory of his lost friend – suddenly so present in the gestures and physicality of his son. If only he could impart his hard-won knowledge on these hot-headed kids, the movie suggests.

These midlife crisis movies could be seen to offer a different kind of machismo: a softer, more protective, empathetic and emotional type. Yet it’s also hard to shake the feeling that the whole thing is just wish-fulfilment for moviegoers convinced that their youth was cinema’s golden age – the same lads that might have drifted over to the navy recruitment booths a few decades ago. Let’s show the kids what it was like in our day. Let’s show them we’ve still got it, and we’re wiser as well as older now too. Watching these middle-aged action men approach that crisis point, get lauded for their performances, and prove they’ve still got it, it’s also hard to shake the knowledge that Kelly McGillis and Meg Ryan weren’t asked to return. Some ageing processes still aren’t given the Hollywood treatment.