The co-curator of the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture reflects on how the rituals of immigrant communities can shape cities and their design

‘There is a reason, after all, that some people wish to colonize the moon, and others dance before it as an ancient friend’, James Baldwin noted in No Name in the Street, his 1972 reflection on the Black experience in Europe and America of the 1960s and early 70s. Baldwin refocuses his metaphorical telescope on what it means to live in and among others: other people, other objects, other ways of being. This trilogy neatly sums up mine and my co-curators’ – Joseph Henry, Meneesha Kellay and Sumitra Upham – definition of architecture; it runs contrary to the hegemony of a profession that still pays far too much attention to the literal building of walls, when the space and streets between them is where society unfolds and our experience of a place is shaped.

Baldwin’s ‘ancient friend’ is the guiding force behind Dancing Before the Moon, our exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia’s 18th International Architecture Exhibition. The exhibition aims to shift our collective gaze so as to centre on how Britain’s diasporic communities – through their active occupation of the spaces in-between – help to construct the supportive framework of contemporary British life. We looked to celebrate how, through everyday ritual acts like dance and worship, they shape the architecture of the world we live in.

This definition of architecture should not be read as radical. It is inevitable that our experience of a city will be informed by the activity that takes place within it. The drama that occurs once the curtain falls in a theatre or concert hall, sending the audience spilling into the streets; the euphoria that engulfs the area around a sports stadium at the strike of a ball. British society values these rituals – opera, theatre, football – and we construct grand walls around them, give them roofs to keep them dry in any weather. Where Dancing Before the Moon becomes radical is in its advocacy for non-eurocentric pastimes to be afforded the same honour as these historically white-European rituals. Instead of the rituals of Black and Brown communities in the UK taking temporary shelter in community halls perennially at risk of closure, or otherwise resorting to the street, we wish to see these rituals valued, housed and cherished.

Through the presentation of six large sculptures by emerging artists and architects, as well as a new film (also titled Dancing Before the Moon) directed by Henry, Kellay, Upham and myself, the exhibition presents an architecture that sits at this meeting point between the immaterial and the material, where (much like Baldwin wrote) a dialogue is set up between that which is inherently light – the fleeting, ephemeral and spiritual acts of performance, procession and care – and that which is inherently heavy: the neocolonial pavilion building itself, laden with the iconography and legacy of conquest, empire and trauma.

At the core of this idea is the empowering act of occupation, that by simply being in a space one can change its very nature. And so the sculptures are architectural in scale: an asteroid-marked, three-metre-tall aluminium monolith by Madhav Kidao meditates on the liminal moment between death and rebirth that exists in Hindu and Buddhist philosophies; a seven-metre-long tableau made of blue soap by Sandra Poulson depicts the artist’s delicate memory of Angolan street scenes, where the removal of dust (from people and objects) is almost a religious act. Situated in the centre of each of the pavilion’s five peripheral rooms and its entrance, these sculptures fill the void to challenge historic power dynamics whereby the contribution of the Black and Brown communities in Britain is easily forgotten and deliberately ignored. Instead, these objects are large, present and entrenched; they demand acknowledgement, respect and renegotiation.

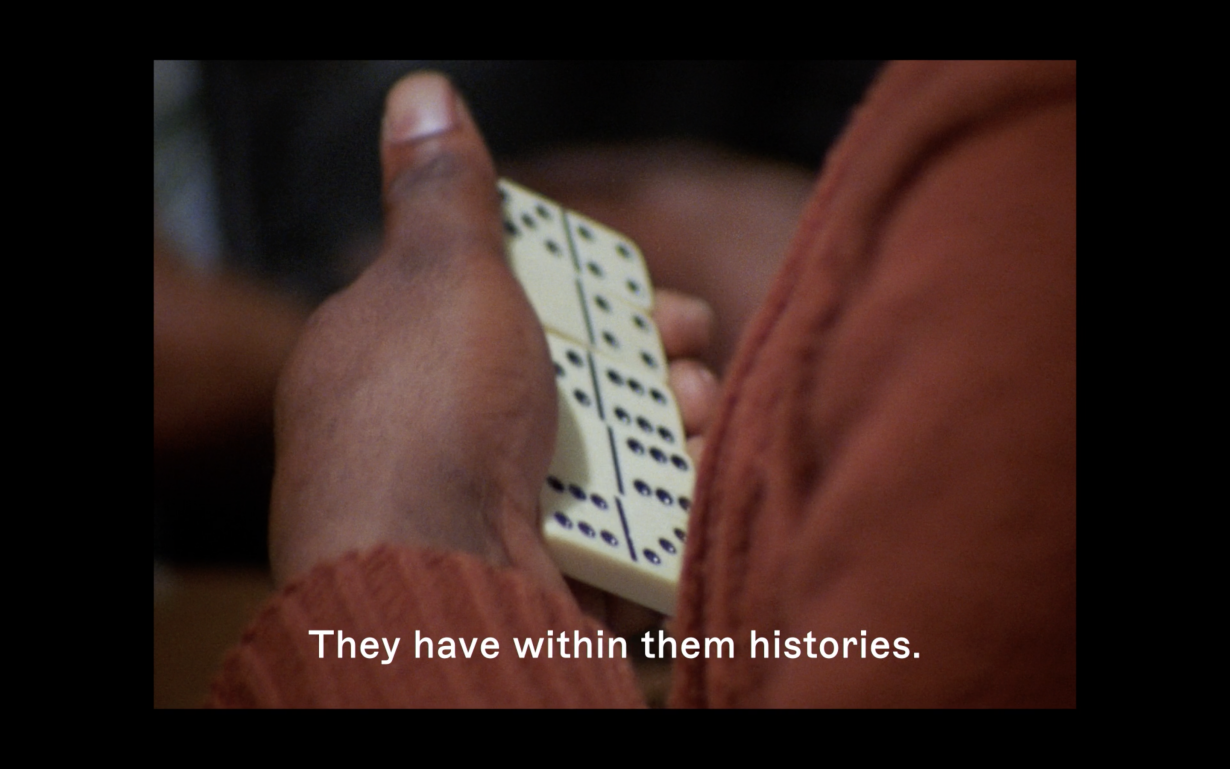

The film, located at the centre of the pavilion, binds the exhibition together. Combining rarely-seen archive footage from the British Film Institute and new footage shot around the UK, the film observes rituals performed by Black and Brown people in Britain. Archival scenes of dominoes being played in London, as depicted in Franco Rosso’s Dread Beat and Blood (1978), are intercut with similar scenes from a Nottingham pub captured this year, demonstrating how stereotypically British spaces can be transformed via a Caribbean overlay, where dedicated dominoes tables replace more traditional bar counters and Midlands accents merge with patois. Rosso’s additional depiction of the West Indian soundsystem culture of the 1970s, with its makeshift analogue glamour, is juxtaposed with observations by the artist Hark1karan and his chronicle of West London’s contemporary South Asian car-tuning culture where similarly homemade devices transform classic sports cars, in a shared love letter to dub, roots and reggae music. Like Baldwin and his commune with the moon from earth, these conversations span time as the film oscillates between past and present to locate a canon of Black artistic practice where antiphony is central.

At moments, the film’s active dialogue between history and the present reaches beyond the screen to speak to the physical works that surround it. During one sequence, found footage of a Trindadian steelpan maker tuning a single pan (Steve Shaw, Steel ‘n’ Skin, 1979) produces ripples of high-pitched sound before they coalesce to form a bundle of stars, in a reference to the vast steelpans that hang at the pavilion’s entrance, fashioned into boat-like forms . This eight-metre-long sculptural installation Thunder & Şimşek (the latter being Turkish for ‘lightning’) designed by myself is a response to my own hybrid heritage and ancestral connections to the islands of Trinidad and Cyprus, both having been shaped and scarred by British occupation. In their form and metrics, the twin vessels evoke the confinement and horror of ships used to transport enslaved people, but in their materiality they simultaneously embody positive, celebratory references – to the steelpan tradition of Trinidad (the ‘thunder’) and to the makeshift pans that form a cornerstone of outdoor cooking (the ‘simşek’) in Turkish-Cypriot communities, evoking the heat and energy of the sizzling grill around which my family in North London gathered on weekends.

While working on Dancing Before the Moon, I found friendship in the support of two West-London elders, ninety-three-year-old steelpan pioneer Cyril Khamai and Notting Hill Carnival leader Haroun Shah. Their stories of carefree invention, rooted in the twinned geographies of San Fernando, Trinidad and London, gave me the confidence to turn seemingly disparate notes of influence into new compositions – much like the steel pan musician-magician of our film, tweaking his instrument until he found the right tone. Baldwin speaks of dancing before the moon as an ‘ancient friend’, framing this distant presence as a constant neighbour in our lives. Cyril, Haroun and the ancestors presented in the film are similarly present figures. Their ways of being fill the space between walls to define a new architecture of belonging, one that is at once Black and Brown and British.

Jayden Ali is the founding director of JA Projects and lecturer on Central Saint Martins’ MA Architecture course