Vivono (‘they live’) is an at once lyrical and luminous engagement with a history of pain

HIV-AIDS: two sets of capitals that make the heart sink – or at least, that would seem to be the only possible emotional response to an exhibition that deals with a history of pain, mourning and suffering. Contrary to expectations, Vivono (‘they live’) turns out to be both lyrical – in part because of the abundant presence of poetry, blended with visual artworks – and luminous. The exhibition spaces are bright and airy, and both the language and the works on show are alive in the way they inhabit the galleries, alternating different rhythms and levels of concentration.

On a monumental projection screen is Vivono (2025), a film by Roberto Ortu, in which contemporary artists and activists read a small anthology of poems by those who lived with or wrote about HIV-AIDS. The latter were people who experienced an epidemic that extinguished the protesting and revolutionary euphoria of the 1970s and ushered in the 1980s, representing a tragedy not only of health but of collective and political dimensions. HIV-AIDS struck gay and bisexual men hardest, but the real catastrophe was a government and culture whose hatred and indifference let the virus tear through entire communities. It is a crisis that deeply marked the lives and struggles of LGBTQ+ movements, not only through viral transmission but also through stigma, institutional silence and an inadequate healthcare response shaped by homophobia. Just behind the screen, one glimpses a poem by Massimiliano Chiamenti that reads ‘Splatter my heart, honey… /please!’; and a little further on, Gea Casolaro hides the acrostic ‘AIDS’ in the title Amore un’insidia s’annida (‘Love a danger is lurking’), a poem printed on a mirror. The exhibition is full of poetry: printed on paper, projected on walls, whispered through audio.

From the second room onward, works intermingle with a small crowd of noticeboards filled with documents that make clear one of the exhibition’s main intentions: to make us aware of how little we know about the years between the first recorded cases of AIDS in Italy, in 1982, and the introduction of lifesaving combinations of antiretroviral drugs in 1996 – just a year after the highest number of AIDS-related deaths in Italy was recorded. Each board gathers archival materials around a specific theme, like ‘Virus’, ‘Stigma’, ‘Time’, ‘Shit’, ‘Isolation’, ‘Community’, ‘Feelings’, all assembled for the exhibition by a group of HIV-AIDS activists. In these first rooms, the archival materials blend seamlessly with artworks that serve as testimonies from those who created art out of a fear of vanishing. There is Bruno Zanichelli with figurative paintings such as Senza titolo (Scatola rossa) (1988), where a red box occupies the centre of a turbulent sea, whose dry, essential graphic line recalls illustration. He painted in acrylic over the course of his brief career with the urgency of someone watching their existence become thinner and thinner. And there is Vittorio Scarpati, who, using pen and markers, filled the pages of a notebook with comiclike drawings depicting himself in a hospital surrounded by animals and angels – the only way he could communicate once pneumonia had stolen his voice.

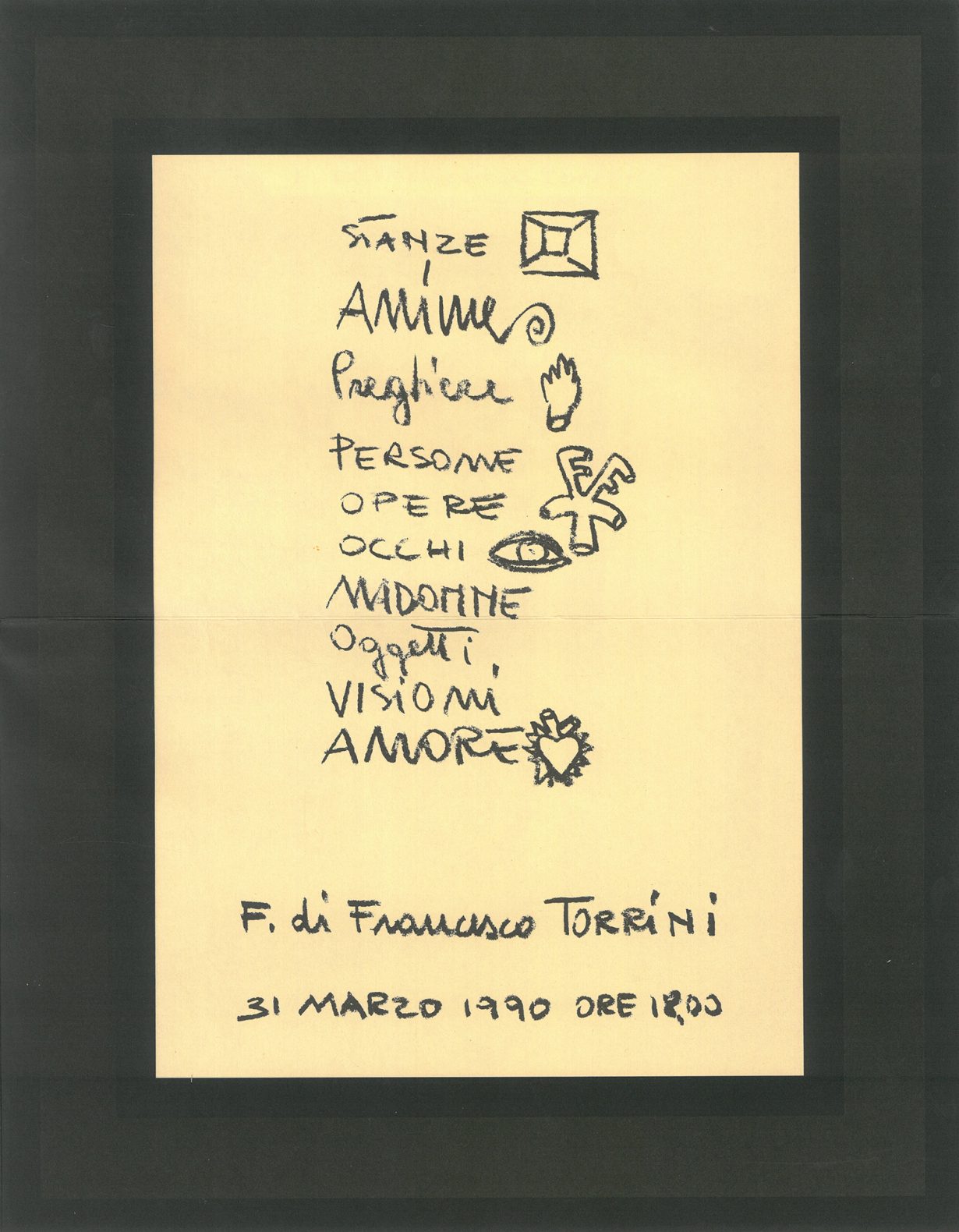

By the third room, the anxious, dutiful impulse to record everything and read every document gives way to a more relaxed attitude. This coincides with a contraction in the exhibition design – as if the show were in a spasm or flexing like a muscle – with three monographic rooms, each dedicated to an artist whose work shares an approach that intertwines body, word and image. The first, dedicated to Francesco Torrini, recreates the setup of a room in his home for a domestic exhibition, Stanze (‘Rooms’), held in 1990. His coloured pencil drawings recall the language of ex-votos: hearts, chests, many eyes, ancient symbols of protection and exorcism. The second, dedicated to Patrizia Vicinelli, seems pulled inward by a centripetal force, coagulating at the centre of the room in four cabinets whose mirrored surfaces face inward. These contain poems written on sheets of paper and, within their hollow interiors, seats where one can listen to the artist’s voice whispering her verses, where time, once again relentless, seems to bite at her ankles. In I have No Time (1978) she writes: ‘Time reaches her, finished time’. And later ‘the hours up to that point had silent run HAD RUN OUT, she knew she was risking, every minute, the painful ending, the fulfilment, and she still tried to postpone it’. The final room contracts further into the form of a living room, complete with sofas, dedicated to activist Nino Gennaro, whose poems, fragmented, sharp and self-ironic, are projected onto the walls. One, written on a t-shirt, goes like this: ‘Either you are happy or you are complicit’. Another, on a sheet of paper, begins like this: ‘make your home places of listening for the children of the world’.

The exhibition’s design functions like a temperature gradient traversing the space, shifting from a more rarefied, documentary atmosphere to one more domestic and intimate. This contraction seems to acknowledge a moment of community within those brief years between 1982 and 1996, a period of upheaval often described in historical literature as one of anthropological mutation, marked by the end of collective narratives and disillusionment. Yet here it is recognised as a time when a community, forced to relinquish the public dimension of body politics that had filled the squares of the 1970s, found new forms of intimacy and solidarity, within affection and queer family. The result is an exhibition that presents itself as a living space, one that is raw and emotionally exposed.

Vivono: Art and Feelings, HIV-AIDS in Italy. 1982–1996 at Centro Pecci, Prato, through 10 May

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.