The confrontational artist has let visitors shoot him with thousands of paintballs, surgically attached a camera to his head for a year, and produced a videogame called Virtual Jihadi

Wafaa Bilal’s Indulge Me is the first retrospective of an artist whose work has long held up a mirror on empathy and its limits. Indulge Me surveys two decades of disarmingly intimate and unexpectedly dreamlike confrontations engineered by Bilal, an interdisciplinary artist who lived in Iraq when the country was ruled by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party and began his art career in the US around the time American President George W. Bush launched the ‘War on Terror’ in 2001.

In the first gallery, viewers are confronted by a facsimile of the set for the artist’s 2007 project Domestic Tension, a paint-splattered cell equipped with a bed, a chair, a computer and an automated paintball gun that appears to have been fired thousands of times. For the original

2007 project, Bilal lived in the makeshift cell – a converted room in Chicago’s former Flatfile Gallery – for 30 days, livestreaming his time there as he allowed viewers to shoot him with a similar internet-controlled gun. Consequently, Bilal was shot hundreds of times by online viewers from over 130 countries.

Domestic Tension reads as a work of unbearable intimacy, a claustrophobic and masochistic expression of grief in response to the death of the artist’s brother as the result of an American drone strike. The facsimile, however, is empty, and though footage of the 2007 project plays on the walls at the MCA, Bilal’s absence changes our relationship to the work. After all, as he was livestreaming in 2007, Bilal continually spoke with and developed relationships with audience members, spectators and shooters alike. The footage seems to memorialise these interactions, which occurred at a time when many Westerners, especially Americans, still shared an almost utopian vision of the Internet as a ‘global village’. Since then, netizens have become atomised, mutually distrustful and hyperaware of their relationships to suffering inflicted by proxy – and consequently more risk-averse, closed off to mess and culpability – a transformation that has rendered us more like the dissociated drone operators of modern warfare than we’d like to admit.

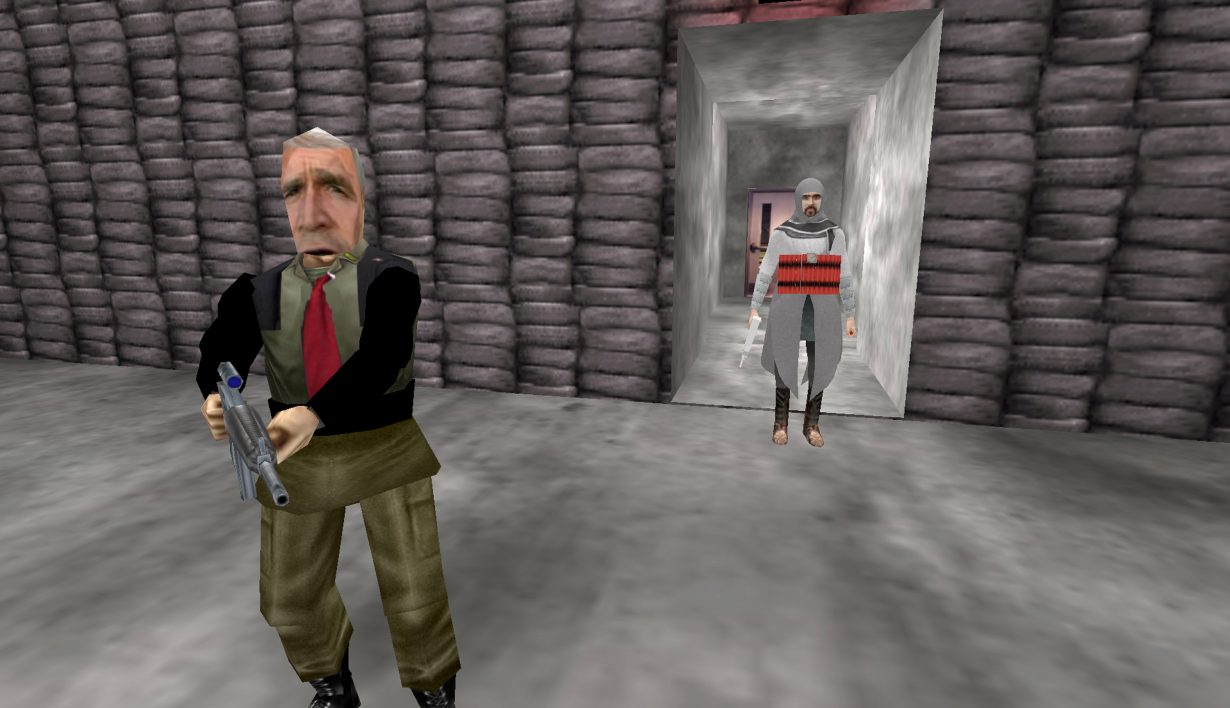

Such a queasy realisation begets an uneasy intimacy. There’s a friction inherent to the act of watching Bilal’s work, which asks us to confront how we look and what we see when we see the artist. This is evident in the largescale screening of footage from 3rdi (2010–11), a performance in which a camera was surgically grafted to the back of the artist’s head for a year, and Bilal’s computer game Virtual Jihadi (2008), displayed under the flickering lights of an installation recalling an early 2000s Baghdadi internet café. 3rdi shows the eyes of others following Bilal’s movements, literalising the surreal experience of everyday Islamophobia. Although we are also spectators, we can distance ourselves from – and even judge – those caught on Bilal’s camera. In Virtual Jihadi, we play as shooters tasked with killing American soldiers. Like drone operators, we sit alone, frantically pressing the space bar and enter button. Blood is rendered in 8-bit animation, and though soldiers can return fire, ‘death’ is only an end screen. The effect is disquieting, even if in the eighteen years since Bilal created the work the rise in live-streamed violence and mass killings in schools or other public places has only further desensitised us.

There’s a dreamlike – or nightmarish – quality to Bilal’s work, born of these intimacies that seem impossible and circular, of memories that resist linear designs but exist as imperfect, changing and elastic collections of starts, stops and loops. Bilal takes us on a journey formed by crossings and in-between spaces where he reveals something about the volatility and fragility of empathy.

Indulge Me at Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, through 19 October

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.