How the late artist’s work demonstrates that you’re not alone

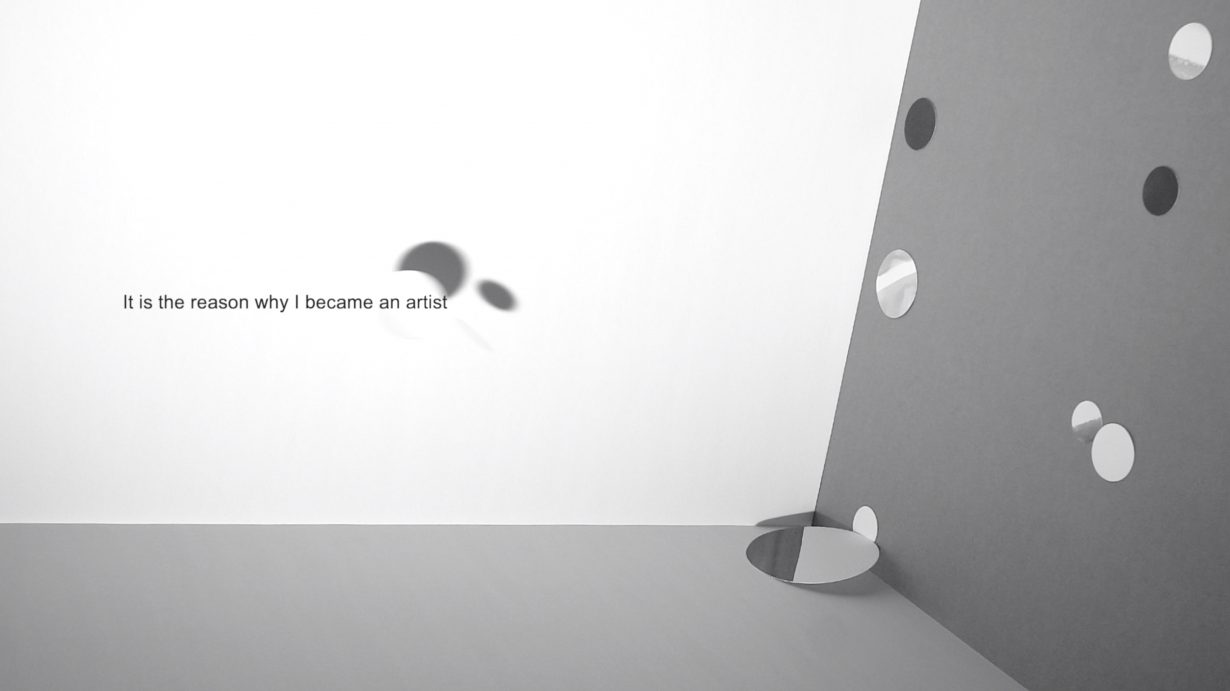

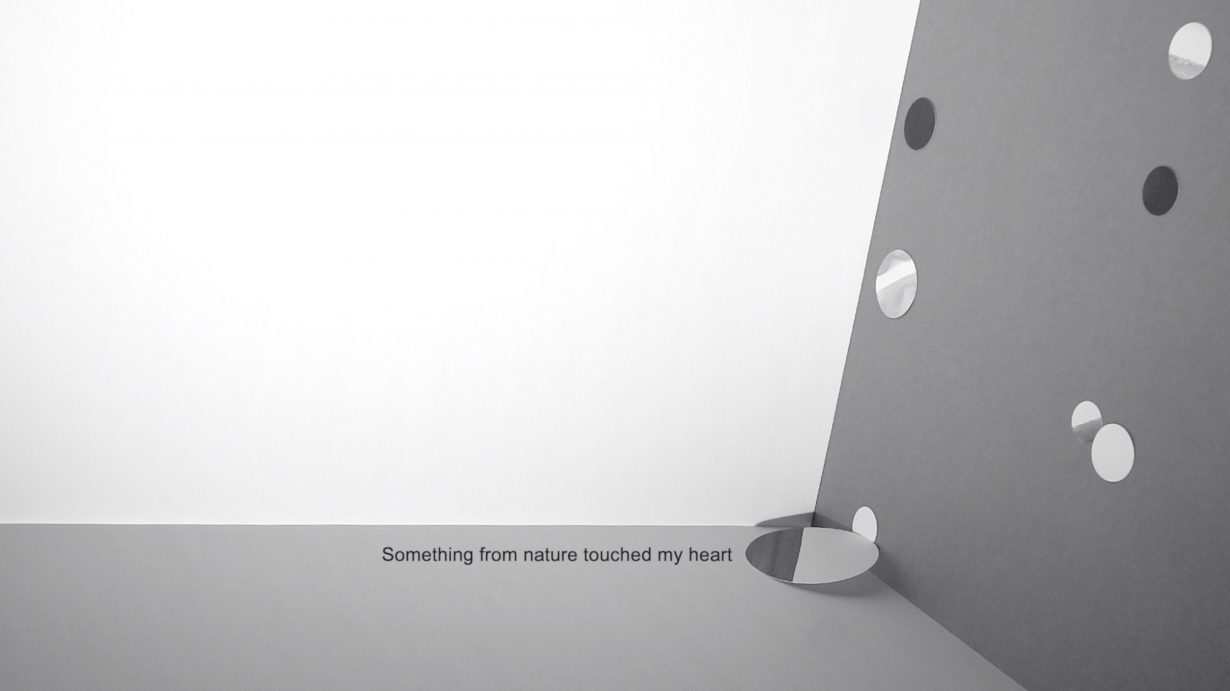

In a room, circular pieces of cardboard are falling in slow-motion onto the floor, bouncing off lightly before landing, so that you can see the sides are painted in different shades of grey, white and black. This is Taiwanese artist Wang Ya-Hui’s 2021 video The Smell of Rice Field. It’s silent, but it finds Wang in an unusually confessional mode. She has rotated the angle of the video by 90 degrees, so that the cardboard pieces fall from left to right – a move that invokes the movement of wind rather than gravity. The softly falling circles, as well as the split second of anticipation to see which way each circle lands, conspire to induce a state of hypnotic attention. Flashing line by line is a text written by Wang about her experience of being assigned to teach in a school in the countryside after university. At that time, she’d been experiencing episodes of depression, but after spending time in a rural environment, ‘surrounded by mountains and rice fields’, she felt her mind clear up, ‘like a bottle of clean water with the dust settling to the bottom’. ‘Something from nature touched my heart,’ she writes, ‘and now looking back, it was the reason why I became an artist.’

This feeling of tranquil sedimentation and calm authority can typically be found in Wang’s two-decade oeuvre, which spans photography, video and installation. Wang died in 2023 at the age of fifty. Despite her sizeable body of work, she is more well-known in her native Taiwan, where she established her name by winning the Taipei Art Award in 2002 when still a master’s student, with her first computer-animated videowork Falling (2002). It depicted everyday items floating above a table, with objects randomly smashing violently down to the ground. Since then, she has been a key figure in the local video-art scene, participating in the Taipei Biennial thrice (including posthumously in the latest edition in 2023), as well as internationally in places like the Hors Pistes Film Festival at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (2008) and the Shanghai Biennale (2006).

Originally on track to study law at university, Wang had no formal training in art when she decided to enrol in the Fine Arts department at National Taiwan Normal University. There she mostly painted. Later, while pursuing a master’s degree in New Media Art at Taipei National University of the Arts, she started making short films and video art. Her early work was whimsical and tricksterish, and focused on playful visual illusions. The video installation Gap (2002) features a projected image of a wall. At regular intervals, one side of that wall swings slightly open, like a secret door, revealing a sliver of an external landscape, like a busy street or a park. In the video When I Look at the Moon (2007), a moon darts around erratically in the night sky above a quiet street – an incredible sight, almost like a ufo sighting, yet one to which the odd passerby is oblivious. It’s only when this dancing moon disappears into the right edge of the video’s frame, and a beam of light breaks against a lamppost in the foreground, that you realise the whole thing is a lighting trick. The moon is actually a white balloon, attached to a string, onto which Wang shines a high-beam torch and tugs around from the ground. Eventually she cuts the string and the balloon floats higher and higher, disappearing into the dark. A separate photograph of the same title, showing the artist holding the stringed balloon reveals the technical setup. The playful visual rhyme, balloon-moon, makes the work even more charming.

Another iconic early work is Visitor (2007), in which Wang presents, with poignant detachment, the house belonging to her grandparents, in which she spent her childhood. The film opens with a shot of clouds in the sky and, through a series of jump cuts and subtle CGI, one small cloud is shown passing through the front door of the rundown two storey house and gliding serenely through the rooms. This wispy white puff, about the size of a football, floats past gleaming darkwood furniture, plastic stools, yellow walls, a barometer, palm grease around light switches, a Chinese landscape painted directly onto a wooden door. In the master bedroom, we encounter two separate beds with orange velvet coverlets, and in front of them, two separate chairs, heavy as thrones. Eventually, the cloud drifts out of a window, past the house’s corrugated zinc roofs, over the river and into the sky again – finishing its leisurely tour of the mundane world.

In her 2017 essay, ‘Five Dialogues’, Wang articulated her own creative philosophy and aspirations, writing about five creators whose work had influenced her. Among them were the writings of minimalist Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, whose sentences make her ‘think that the most moving things are often pointing out the simplest facts, but this pointing out must come from a place of vision and deep feeling’. A part of her work brings mundane objects together, in as unaltered a state as possible, to allow the materials to speak for themselves, a gesture reminiscent of the Mono-ha movement. The video Notebook (2020) was inspired by Wang’s personal practice of jotting down ideas and impressions on random pieces of notebook paper. In the videowork, differently coloured, lined and gridded papers are shown gliding over each other horizontally and vertically, creating a series of screenwipe effects. At the top right corner of the screen is a constant rhombus shaped patch of light, as if someone had opened a window to let the sun in. The smooth and steady parade of these blank notebook pages imbues a grave dignity in them. Meanwhile, in the kinetic sculpture I am a branch (2012), she picked up fallen tree branches from a construction site and arranged them, upright, in a row. A motor, attached to the bottom of each branch embedded in a low plinth, rotates them slowly one after the other, so we see the unique form of each pirouetting broken branch, whether smooth or gnarly, curved or straight.

In her later work, she would turn to time as her great theme. In her exhibition essay for her 2019 solo exhibition, A Brief History of Time, at Taipei’s Eslite Gallery, Wang wrote: ‘I view time as part of the very texture of things, not as an external measurement.’ In early works like The Visitor, the historied environment indirectly speaks to this thought, but later on, time as embodied in the flow of abstract forms becomes the subject of her work. For the video installation The Book of Time #1 (2019), she layered light effects to create a mesmerising and rhythmic unfolding of shapes: first, she shone a beam of light onto a standing piece of cardboard shaped like an open book, creating shifting lines and planes. These effects were recorded on video, which is then projected onto a wall and other objects, like notebooks and bits of folded cardboard, are arranged in front of the wall, creating yet more overlapping planes of light and shadow. As a result, we experience time as it unfolds spatially and rhythmically, a slow dance of extensions and retractions, conjunctions and separations. Time is inseparable from her ever-evolving lines, planes and angles, constantly extending, breaking and joining.

Many of Wang’s works operate in a realm of abstract form and movement. But the patterns of arising and passing through in her work resonate poignantly with the cycles of life and death, which Wang’s last work, the video installation – – [one and one] (2022), makes more explicit. Two small towels are hung on a wall, while moving rectangles of light and shadow are projected onto them. The rectangles move downwards, and the visual effect suggests that the towels are moving upwards. Sometimes, emerging from dark to light, the towels resemble little buds bursting out of the soil; when the dark passes over them, they are buried in the earth. In a tall and narrow rectangle of light, the towels seem to be ascending jubilantly. Of course, all this time, the towels are completely still. one and one is described by Wang in her notes as being about ‘a dialogue over time’. Indeed, the work does present an ebb and flow of time poetically, but the fact that the towels are a pair suggests a rebuttal of sorts. That despite constant change, there is steadfast companionship that remains resolute even through thick and thin, life and death; that something indefinable remains.