The life of Hitler’s favourite filmmaker offers a blueprint for understanding the rise of fascist aesthetics today

It’s 1976, and in a studio in Cologne, a lushly bearded talk show presenter introduces his guests. Before him sit two women in their seventies, both with neat perms. One, Elfriede Kretschmer, is a trade unionist from Hamburg. The other, the host tells us, is someone we already know: notorious Nazi-era filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl.

As the conversation begins, it becomes clear that this interview is the broadcaster’s attempt to address a past that until now Riefenstahl has publicly sidestepped. Kretschmer, a former anti-Nazi activist, questions Riefenstahl’s assertion that she was unaware of atrocities being committed during the Third Reich. “I was saddened that a woman would make films that were against all of humanity,” says Kretschmer, referring to Riefenstahl’s 1930s propaganda films. “I’d be happy if I’d witnessed [atrocities] like you, I’d be so happy!” Riefenstahl counters, as Kretschmer shuffles irritably on her chair. “These days it’s much more difficult for those who didn’t know because no one believes them.” Riefenstahl leans back into the soft sofa with a sigh of frustration. In the background, an audience watches on in semi-darkness.

This sequence is one of several haunting pieces of archive television which punctuate Riefenstahl, a new documentary by German filmmaker Andres Veiel. Riefenstahl’s life has been filmed before, most notably in Ray Müller’s The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (1993), which featured extensive interviews with the then 90-year-old filmmaker. A decade earlier, Nina Gladitz’s investigative television documentary Time of Darkness and Silence (1982) had refuted Riefenstahl’s repeated claim that she knew nothing about the crimes of the Holocaust, revealing that Riefenstahl had cast Sinti and Roma concentration camp prisoners in her film Tiefland (Lowlands) in the early 1940s. However, while both Gladitz and Müller’s films were made while Riefenstahl was still alive, Veiel’s arrives two decades after her death, and is therefore able to position itself as a comprehensive biographical portrait. Veiel also benefits from access to the filmmaker’s estate, drawing upon previously unreleased material including letters, photographs, film footage and even audio recordings of private telephone calls, alongside films and television appearances.

The result is hypnotic, unsettling and sometimes infuriating. By drawing parallels between Riefenstahl’s work as a filmmaker – a role she used to twist reality as she served Nazi ideology in her propaganda films made for the regime – and her later prominence as a public figure – presenting a counterfactual account of her life on German television – Veiel positions Riefenstahl as a kind of post-truth pioneer. Although comprised almost entirely of twentieth-century archive material, the film implicitly argues that Riefenstahl’s manipulation of her audience – both via her filmmaking, and through her postwar public appearances – provided a blueprint for future purveyors of fake news, misinformation and conspiracy theories. At the same time, Veiel must balance this argument about Riefenstahl’s ongoing relevance with the risk of further burnishing her notoriety. Any film potentially feeds into the morbid fascination which surrounds Riefenstahl in the German public imagination, fed by her glamour and striking beauty but also her novelty, both as a prominent woman associated with Nazism and a rare example of a successful female filmmaker of the interwar period.

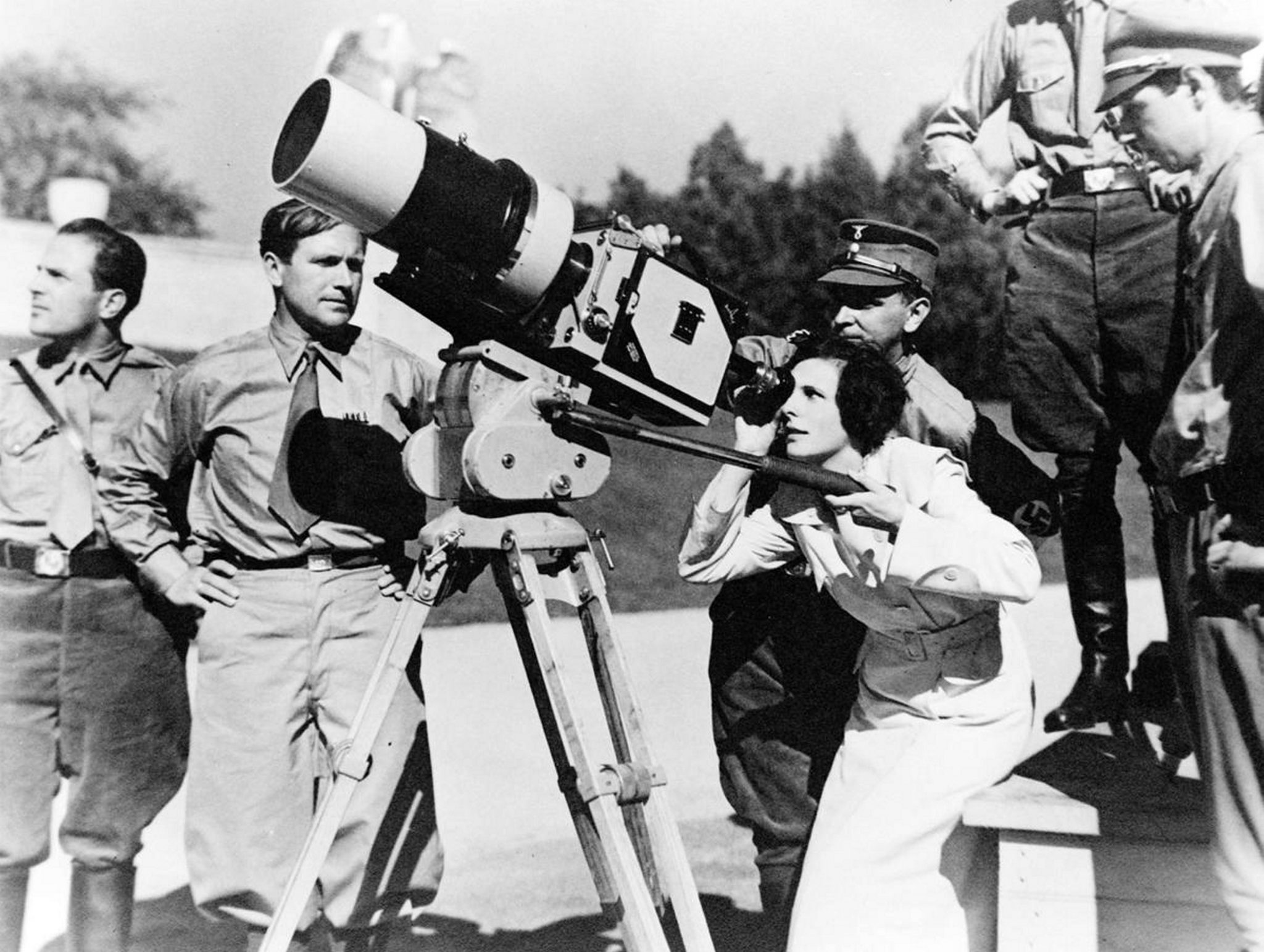

The bare facts of Riefenstahl’s life are undeniably compelling. Born in Berlin in 1902, she rose to fame in the 1920s, starring in a series of Alpine-set adventure movies. In the 1930s, she moved into directing and became internationally famous thanks to two films, described at the time as documentaries: Triumph of the Will, which centres on the 1934 Nazi Congress in Nuremberg, and Olympia, about the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Both films were celebrated as masterpieces, not just in Germany but across Europe, screening to critical admiration at the Venice Film Festival. They were also potent works of propaganda commissioned directly by Hitler, in which Riefenstahl channelled vast budgets, cutting-edge technology and her own formidable artistic talent in service of Nazi ideology. After the Second World War, Riefenstahl was tried four times by the postwar denazification courts, but was declared to be a sympathiser, a ‘fellow traveller’, rather than an active participant in Nazi crimes, so faced no further punishment.

She managed to complete Tiefland, released after many delays in 1954, but her film career stalled, the association with Hitler proving too offputting for investors. Instead, she carved a modestly successful second career as a photographer, and spent the rest of her life (until her death in 2003, aged 101) distancing herself from her Nazi benefactors and painting herself as a naïve artist in the wrong place at the wrong time. Towards the end of her life, it looked like that rehabilitation had partially succeeded; in 1998, the elderly Riefenstahl was a guest of honour at Time magazine’s 75th anniversary party, where she received a standing ovation. She never publicly admitted to knowledge of Nazi crimes during the war years, nor acknowledged that her role as a propaganda filmmaker had contributed to the party’s power.

The clips from that 1976 talk show stick in the mind because they encapsulate, in a single exchange, the disquieting dynamics which have long shaped Riefenstahl’s public image. When Riefenstahl, elegantly dressed and pleading ignorance, talks of her shock at discovering Nazi crimes after the war, she frames this experience through her own victimhood. “I, and many others, will never be able to heal and recover,” Riefenstahl declares. “That’s why I have always avoided doing these talk shows. This is the first one I’ve agreed to do in many years, because these wounds have still not healed.” At these words the studio audience break into applause.

Throughout the second half of her long life, Riefenstahl would publicly perform misunderstood victimhood (far from avoiding talk shows, she turned them into a steady earner – Veiel’s film includes a recording of a private phone conversation with Nazi architect Albert Speer in which Riefenstahl shares advice on negotiating interviews, declaring that she doesn’t get out of bed for less than 5000 marks). Riefenstahl relentlessly filed lawsuits against those who accused her of wartime complicity, and it was only after her death in 2003 that her own estate yielded evidence that Riefenstahl indeed was aware of Nazi atrocities, and that she had been personally closer to the regime, than she had ever publicly admitted. Drafts of her memoirs demonstrate how Riefenstahl had repeatedly rewritten accounts of her meetings with Hitler and Goebbels, apparently unsure of how much to reveal. “I had many adventures with Goebbels!” she tells her publisher in one recorded phone conversation, while in another, an outtake from Müller’s documentary, she again alludes to personal encounters with the propaganda minister, before flying into a rage and insisting the conversation is taken off the record.

After the war, Riefenstahl would insist her relationships with high-ranking Nazis had been distant and minimal, but this seems to be contradicted by warm references to Hitler in her correspondence. “My Führer, you know how to bring to others better than anyone else,” she writes in a letter thanking Hitler for sending her flowers on her birthday. Another letter, written by an adjutant to Riefenstahl’s former husband, a high-ranking Nazi officer, describes in detail how she witnessed (and, possibly, inadvertently caused) a massacre of Jewish prisoners while shooting a newsreel in Poland. The film also reiterates Gladitz’s allegation that Riefenstahl knowingly cast concentration camp prisoners, many of whom later died at Auschwitz. Making-of footage depicts Riefenstahl laughing and playing with Sinti and Roma child extras on the set of Tieflands. She would later claim, impossibly, that she had personally met all these extras after the war, a lie contradicted by death records from the camps. “Really who is more likely to commit perjury,” she exclaims when confronted by survivor testimony contradicting her claims during the Gladitz court case, “me, or the gypsies?”

While the elderly Riefenstahl, with her blonde curls and pencil-thin eyebrows, appears as a relic from another era, her innovative methods of image-making as a means of propaganda resonates with the ways in which the far-right today employ new technology as a tool for manipulating the public imagination. For Triumph of the Will (1935), Riefenstahl used a pioneering blend of tracking shots, aerial photography, telephoto lenses and cranes to capture the Nuremberg rallies with maximum impact. Olympia (1938) pushed these techniques further, harnessing underwater photography, extreme angles and slow motion to present stylised sequences of athletic bodies pushed to their limits. With Nazi funds, Riefenstahl was able to produce a documentary on an unprecedented scale, developing a new fascist visual lexicon: awe-inspiring crowds, towering leaders, startling images of physical beauty (all the better to bolster eugenicist rhetoric). Riefenstahl’s eager adoption of new technology seems to anticipate the speed with which the makers of far-right media have continued to be at the forefront of the adaptation of new communication technologies, from the eager adoption of deep fakes and AI by the Trump campaign during the 2024 US election, and by Russia during the war in Ukraine, to the far right German party Alternative für Deutschland’s (AfD) mastery of TikTok (a key factor in the party’s recent electoral progress). Just as Riefenstahl’s films distilled complex political ideas into simplistic mythic narratives, so contemporary viral culture thrives on reducing nuanced realities to emotive images. Whether those images are true or false was already, now and in Riefenstahl’s time, beside the point.

After that 1976 talk show, Riefenstahl was inundated with hundreds of messages from supporters. The intensity of this response reflected a wider transformation in German public attitudes towards the country’s recent history. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, there had been little public discourse in West Germany on the Holocaust, with the need to rebuild the country leading to a hasty denazification process which left many former Nazis still in prominent positions. From the mid-1960s onwards, this attitude of denial started to shift, fuelled by generational tensions, student protests and landmark court cases prosecuting Nazi crimes, such as the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, which were widely covered by the media. The principles of open discussion and acceptance of culpability which underpin modern German memory culture were beginning to emerge. Riefenstahl’s television appearance offered a reflection of the new public appetite to talk more publicly about national complicity, but it also tapped into a growing backlash to this new approach. For many viewers, Riefenstahl’s insistence on her innocence echoed their own position. A series of chilling recorded calls between Riefenstahl and these supporters give a sense of the tone of these interactions. “Who was ever more honest than Leni Riefenstahl?” asks one furious caller. Another advises Riefenstahl to “have detachment when it comes to today’s chaotic times… It won’t take that long, one or two generations. Then we will return to morality, decency and virtue.”

Several generations later in present-day Germany, that same memory culture is again the target of intense criticism. For the AfD, rejecting the Schuldkult (‘guilt cult’) has become crucial campaign rhetoric, while many on the left criticise the instrumentalisation of memory culture in support of Zionism and against pro-Palestine activists. The AfD, an organisation which was recently designated as a ‘confirmed right-wing extremist’ force by German intelligence services, now constitutes the country’s leading opposition party. In Veiel’s film, there is a moment in which we are shown an extract from Triumph of the Will, in which crowds gather in front of a giant sign reading ‘Alles für Deutschland’ (‘Everything for Germany’). Watching this sequence I was reminded that at the AfD party conference this January, the party’s leader Alice Weidel had been greeted approvingly by a crowd chanting ‘Alice für Deutschland’, a direct reference to this now banned Nazi-era slogan. It seems clear that German public attitudes to memory culture are shifting once again, and in this process images and ideas immortalised by Riefenstahl’s films are once again floating to the surface. In this battleground, Veiel’s film serves as a reminder that the fight to acknowledge Germany’s dark history was never won. Just as the fascist aesthetics that Riefenstahl pioneered remain highly influential, so the culture of denial remains potent and alive.

Rachel Pronger is a writer and curator based in Berlin. She is the co-founder of archive activist feminist collective Invisible Women