The current explosion of atomic-themed culture tells us something profound about ourselves

‘Another atom bomb test’, says war photographer Augie Steenbeck nonchalantly as he gazes across a desert at a distant smoke plume in Wes Anderson’s film Asteroid City (2023). The line is textbook Anderson glibness, but it also hints at the prevalence of nuclear imagery in the 1950s, when the film is set. At the time, Cold War tensions were acute and the nuclear arms race in full throttle. Images of nuclear tests, usually featuring the billowing form of a mushroom cloud, were prevalent in the media. Existential dread was the new normal. But there’s another reason for the character’s apathy: his wife had just passed away. Death en masse can lose its sting after the death of a loved one.

Since the early atomic tests at Los Alamos, culture has served as a kind of Geiger counter for nuclear fears. In January this year the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reset the Doomsday Clock – a theoretical estimate of how close humanity is to nuclear extinction – to 90 seconds to midnight, the shortest it has ever been. Our heightened collective gloom is evident in the radioactive references that have permeated film and television in the past year: the mushroom cloud has risen across Anderson’s pop-pastel sci-fi and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer; Tom Cruise raced against the clock to prevent a nuclear terrorist attack in the latest Mission: Impossible; Japanese television series The Days (2023) soberly recounted the 2011 accident at a nuclear power plant in Fukushima. What’s clear is that artistic depictions of nuclear technology continue to tug at our greatest anxieties about our precarious present, from war to ecological crisis.

As Asteroid City’s main character exemplifies, atomic themes can articulate inner experience in beguiling ways. The aforementioned litany of atomic subjects in culture reveals that, as atomic anxiety continues to bubble in global politics – in standoffs between Trump and North Korea, in the Russian invasion of Ukraine; threats and escalation by the Iranian government – nuclear power as a metaphor for ourselves feels unavoidable. The possibility of a human-made global wipeout is one of the most psychologically disturbing realities that humans have had to grapple with. It makes sense, then, that cultural expressions of nuclear angst should also become windows into the individual psyche. Salvador Dalí was one of the first artists to draw a link between the bomb’s perspective-shifting effects and the subconscious. His Three Sphinxes of Bikini (1947), inspired by a series of underwater nuclear tests undertaken at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, shows a dream-like scene of a tree, a head and a nuclear test all fantastically morphing into a nebulous cloud. In Oppenheimer, a connection between the bomb and Freudian psychoanalysis is made when the movie’s subject, theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, observes that the library of his lover, the psychiatrist Jean Tatlock, is filled with books by the Austrian. Tatlock immediately fishes out a book from her collection for him to read from while they make love. The same text, from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita, is later repeated in a voiceover during the detonation at Los Alamos, taking us back to that exchange and thus implicating the event as a manifestation of psychosexual desire. This plays into a wider narrative in the film that connects the devastating power of nuclear science with our darker human impulses as the increasingly guilt-ridden Oppenheimer realises he has given humankind a weapon that they cannot help but use.

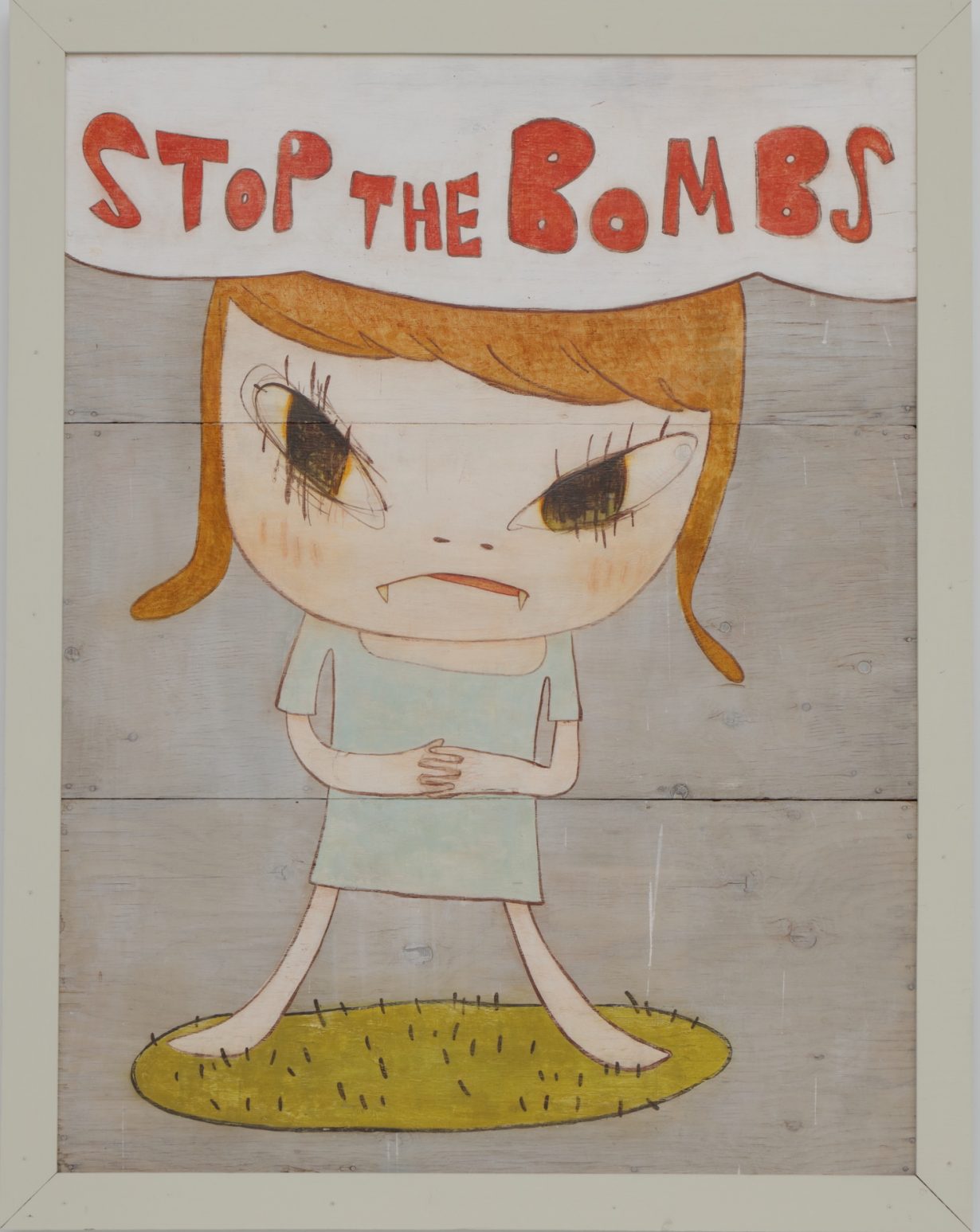

Critics have discussed the allure of atomic themes in art, film and literature in psychological terms in the past. In her 1965 essay ‘The Imagination of Disaster’, Susan Sontag identifies the film industry’s obsessive replaying of end-of-the-world scenarios as a kind of coping mechanism, writing that ‘one of the things that fantasy can do is to normalise what is psychologically unbearable, thereby inuring us to it’. This was particularly the case in postwar Japan, where, Sontag observed, disaster films were repeatedly used to exorcise the trauma of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Some contemporary Japanese artists reverse this escapism by contrasting sunny, sweet forms with dark themes. Anthropomorphised mushrooms and smiling flowers persist as cartoonish warnings in the art of Takashi Murakami. Yoshitomo Nara uses cute, naive subjects in a similar vein; some of his recent portraits of moody children show them alongside anti-nuclear slogans (Stop the Bombs and No War, both 2019). Nara’s use of children is unsettling on multiple levels: their glowering expressions not only equate the capriciousness of youth to an unstable atomic reaction, but are also a worrying reminder of certain tantrum-prone world leaders who love threatening to ‘push the button’.

The 2011 disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant left a deep impression on artists both in Japan and abroad. As the reactors exploded, they released the highest amount of radioactivity into the environment since Chernobyl, leading to the evacuation of more than 160,000 people from their homes, 96,000 of whom were farmers. Artistic responses to the event often explore the effects of radiation on our relationship with the natural world and our sense of self. French artist Pierre Huyghe captures this alienation in his film Untitled (Human Mask) (2014), set in a deserted Fukushima restaurant where there are no humans at all, only a monkey wearing a dress and the mask of a young girl. In a group show exploring the artistic legacies of Fukushima titled Picturing the Invisible – which travelled between the Director’s Gallery at the Royal Geographical Society (2021), the Technical University of Munich (2022) and the Heong Gallery at Downing College Cambridge in 2023 – British photographer Giles Price used thermal imaging to saturate the area’s cattle fields in vivid greens, blues and reds in his series Restricted Residence (2020), strikingly showing how radiation transforms our perception of nature.

Like the death of a loved one, nuclear fallout changes the way we see the world forever. It’s what makes the subject so poised to articulate grief on both a collective and individual scale. In Nick Blackburn’s memoir The Reactor (2022), he writes how he watched videos of the reactor explosion at Chernobyl and saw a parallel between the disaster and him mourning the loss of father: ‘Radioactive atoms want to become stable again so they release energy until they get back to a balanced state’. That Blackburn watches the event on YouTube is telling of the way we consume images of disaster today. In an age of blockbusters, 24-hour news, streaming services and social media, the threat of nuclear extinction is constantly fed back to us in a never-ending loop of catastrophe. Perhaps that’s why we can’t stop seeing ourselves in it.

Kristina Foster is a writer and editor based in Berlin. She covers art and culture for The Financial Times.