Stanley Schtinter’s Last Movies traces the final films that famous people watched

Cinema, the quintessential twentieth-century artform, which became integral to the era’s politics and culture soon after its first demonstration in 1895, has an inherently haunting quality. The obvious reason for this – surely apparent to the Lumière brothers as they captured workers leaving the factory – is its ability to preserve not just the features but also movements and eventually the voices of people for posterity, with more accuracy and less sense of separation from the subject than the earlier method of photography or portrait painting. (Nearly a 100 years since the advent of ‘talkies’, silent film has this eerie property in extremis: long-since deceased actors express and gesticulate in antiquated fashions; different frame-per-minute rates sometimes render their movement strange; and the decay of its stock produces a ghostly effect, making it of interest to contemporary archive-filmmakers such as Karel Doing and Bill Morrison.)

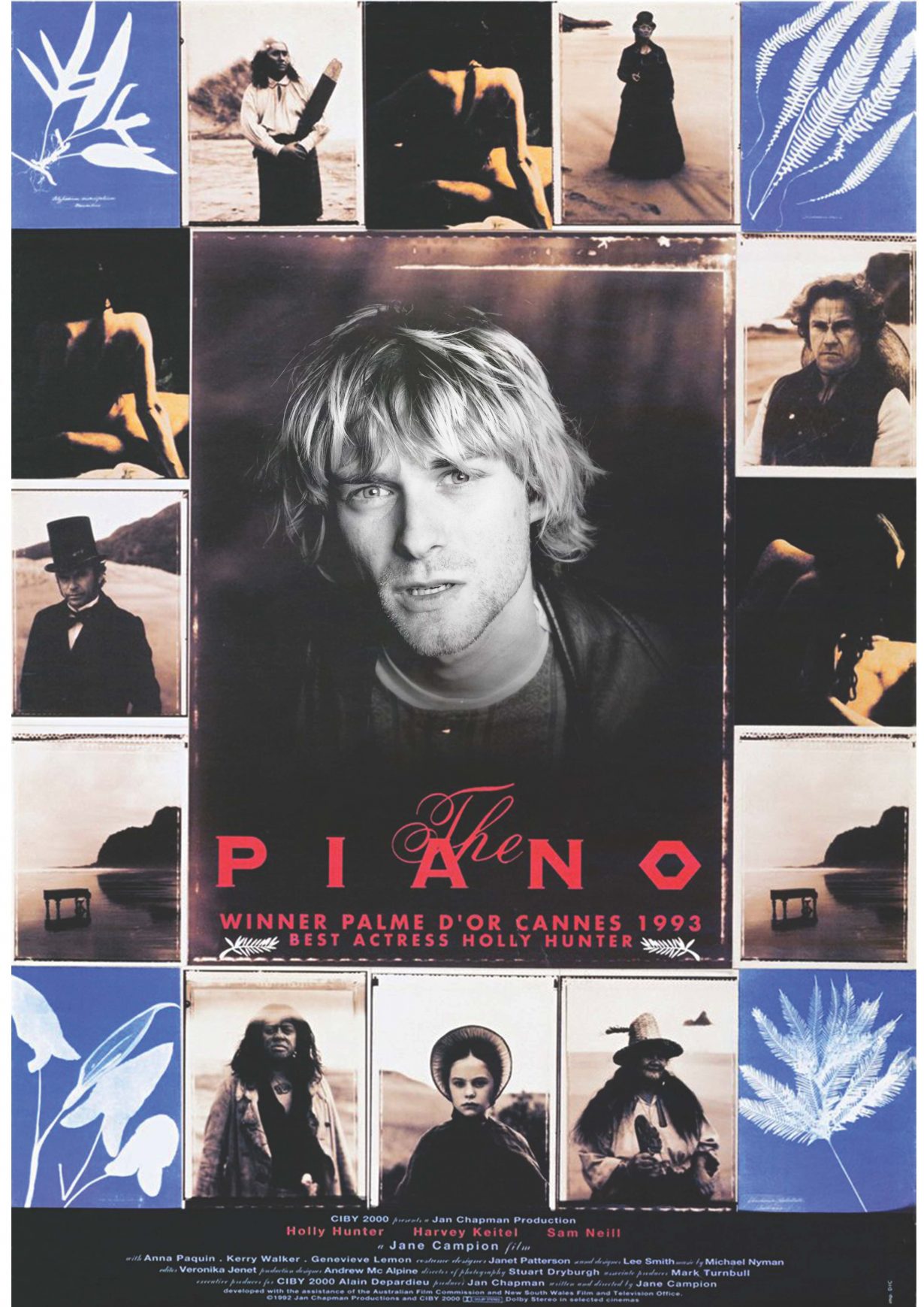

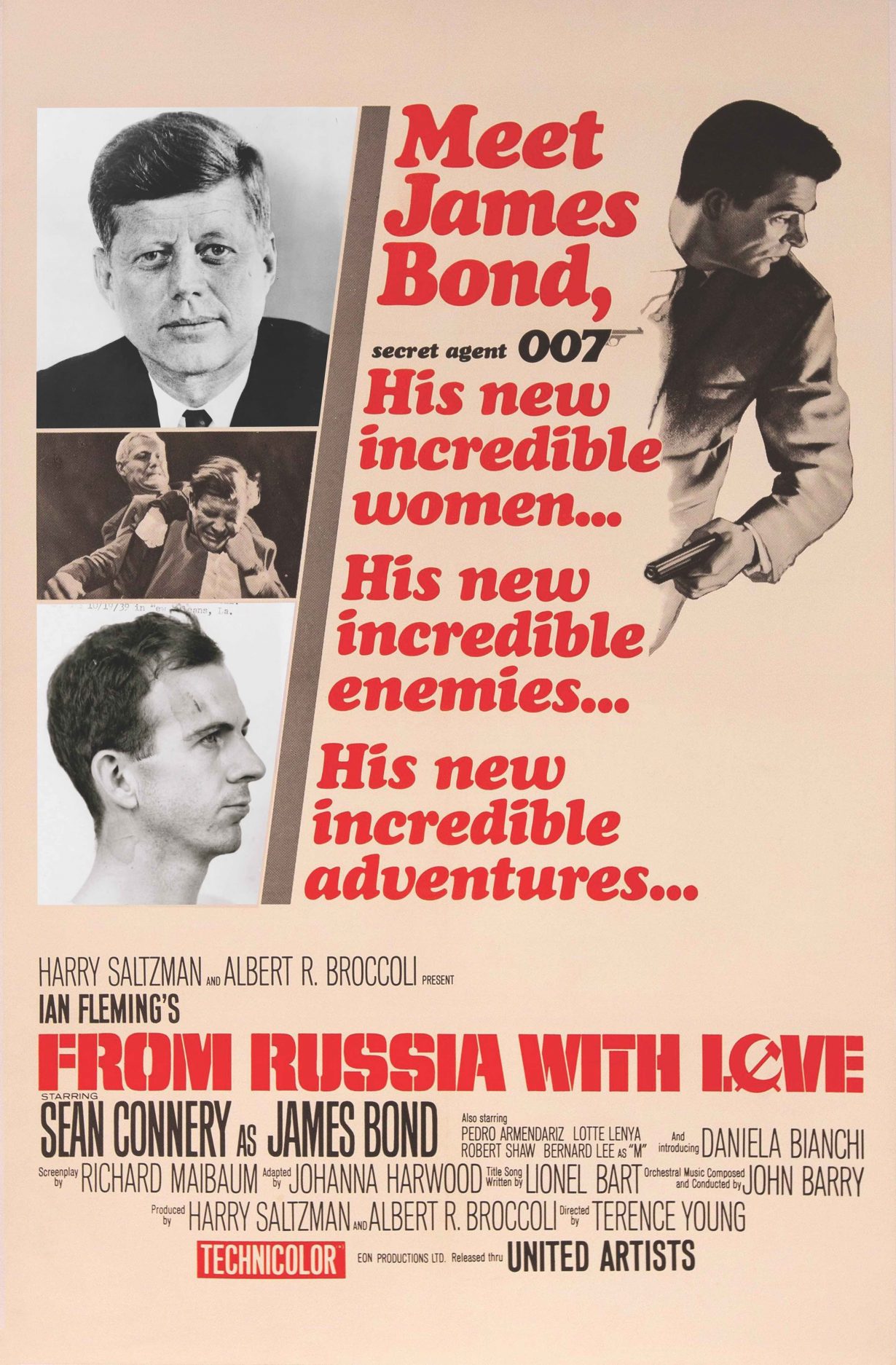

In Last Movies, artist-curator Stanley Schtinter turns the idea, that film captures the dead and turns them into ghosts, on its head. Rather than focus on deceased people onscreen, he finds out (or, occasionally, makes an informed guess at) what was the last film that various important twentieth-century political and cultural figures had watched, bringing together a potted history of the medium itself. He pulls these works into screenings at various venues – including a five-month programme at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, which opens today (22 November), and which includes a diverse range of films from Jane Campion’s The Piano (which Kurt Cobain watched in the cinema after a dinner with friends, two days before his death) to From Russia With Love (1963, which JFK watched in the Oval Office in a screening organised by his special assistant Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., the evening before his assassination). Intriguingly, he has also written a book, arranged with short chapters on various individuals from Franz Kafka to Steve Jobs, that describes the (sometimes contested) facts behind each person’s last film, showing how important the movies were to their lives.

Last Movies is wry rather than morbid, even as it deals with sad or shocking deaths – and the film-related legends that have grown around them. Schtinter notes, for example, that the last film Pier Paolo Pasolini saw was his own Oedipus Rex (1967), where he told a crowd in Stockholm that he expected to be murdered soon. Weeks later, he was. Giuseppe Pelosi, the 17-year-old convicted of killing Pasolini in November 1975, and later pardoned, ‘died in 2017 and nobody wants to know what he saw last’. This may be because, as journalist Maria Antonietta Macciocchi put it, ‘Pasolini was assassinated… by a society which could not bear his defiance (of sexual, political and artistic prohibitions)’ and no one was keen to revisit the case (or find out the last film Pelosi watched). When Italy’s anti-mafia commission did last year, it found the murder was linked to the theft of several reels of Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975),with Pelosi mediating between the director and the organised criminals who killed him. Here, Schtinter cuts through the somewhat murky end of Pasolini’s life, outlining the ultimate lack of justice around the murder with quiet anger.

My own love of arthouse cinema began when I, like countless other Joy Division obsessives, sought out Werner Herzog’s work. I had read Deborah Curtis’s Touching from a Distance (1995), her book about her marriage to Division singer Ian Curtis, with its heart-breaking account of his final hours in May 1980. It includes the legend that Curtis was watching Herzog’s pitch-black comedy Stroszek (1977), about three German down-and-outs in the US, on BBC2 before he killed himself. Much was made of Curtis’s final night by his bandmates and by Tony Wilson, the Factory Records supremo, who said ‘When forced to choose between the truth and the legend, print the legend’. The runout grooves on the vinyl issue of the posthumous compilation Still (1981) refer to ‘the chicken still dancing’: the last thing Stroszek sees, at a dismal roadside funfair, before he shoots himself in Herzog’s film.

Schtinter challenges this legend with a little detective work. Piecing together the timeline from Touching from a Distance and other accounts, Schtinter suggests this (rather too perfect) art-life parallel did not quite line up: Curtis certainly would have lived long enough for the BBC’s later broadcast of J. Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear (1962), and likely have had time to watch it, before writing a valedictory letter to Deborah and listening to one last LP. If so – and we’ll never know – I don’t think it changes much about Joy Division, a group steeped in mythology, not all of which was consciously created, by Wilson or anyone else. Yet this reconsideration is testament to Schtinter’s determined research and willingness to consider the ramifications of a long-held narrative having an inaccuracy at its core.

The highlight of Last Movies is undoubtedly the section on John F. Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald. This draws the two men into a history of film screenings at the White House that goes back to the silent era, when Woodrow Wilson inaugurated the practice by watching D. W. Griffith’s paean to the Ku Klux Klan, Birth of a Nation (1915). Kennedy had a more complex relationship with cinema than any of his predecessors (not least because he was, as The Onion put it, the nation’s ‘first handsome President’), from his father being a successful Hollywood producer to his relationship with Marilyn Monroe. It ended with his assassination on camera and the Zapruder film – the initially suppressed Super-8 footage taken by Abraham Zapruder that was used by the Warren Commission – fascinated generations of conspiracy theorists. (I loved Schtinter’s description of it as ‘an unholy grail of underground movie projections’ and even, playfully, as ‘some kind of genus for an intimate and politically charged filmmaking sometimes called “structural” and “experimental”’: a great connection to North America’s fertile avant-gardescene that emerged around the time of JFK’s death, and one I wish Schtinter explored further.)

Discussing Kennedy and Oswald, who was arrested for murder during a screening of Burt Topper’s War is Hell (1961), Schtinter looks at the serendipitous connections between cinema and several other would-be assassins. Obsessed with A Clockwork Orange, Arthur Bremer planned the killing of Richard Nixon in detail, eventually shooting pro-segregationist Governor George Wallace in 1972, when he was running for president, and leaving him paralysed. Bremer’s diaries inspired Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), with which John Hinckley Jr., in turn, became fixated, shooting Ronald Reagan to attract the attention of actress Jodie Foster.

Last Movies suggests that anyone’s final film viewing could be of world-changing importance – but even if that sounds too hyperbolic, it gives you so many angles from which to look at many different works. Does The Kid (1923) by Charlie Chaplin become sadder or funnier in the knowledge that it was the last film Kafka ever saw? I’m not sure, but it reminds us of how much humour there is in Kafka’s work (though the quote in this essay’s title is from his description in his diaries of 1913 German silent horror film The Student of Prague), how much pathos there is in Chaplin – and how every twentieth-century figure of note had a significant interest in cinema, the era’s art.

Juliet Jacques is a writer, filmmaker and footballer based in London.