What can the centenary edition of The Indian Tomb tell us about our own times?

Three quarters of the way through his celebrated fourteenth-century account of his travels around the world, the Maghrebi scholar Ibn Battuta takes a time out from his description of how he made his ‘escape’ from the service of the rather capricious Sultan of Delhi (who had sometimes been generous with the Moroccan, and at other times a bit scary) – first by giving away his possessions (slaves and all) and hiding out, away from society, as a disciple of a reclusive, ascetic and cibophobic imam, and then (because who wants to live like that for ever?) by getting himself appointed (by the quixotic sultan) to an embassy to China (a job that came with new slaves, new clothes and new horses), during the course of which he was kidnapped and robbed by bandits – to digress on the subject of India’s yogis. ‘The men of this sect do marvellous things,’ he enthuses. ‘One of them will spend months without eating or drinking, and many of them have holes dug for them under the earth which are then built in on top of them, leaving only space for the air to enter.’ He goes on to marvel at the fact that he once met a yogi who had spent 25 days sitting on top of a platform, at the fact that yogis can ‘see what is happening at a distance’ and that the most powerful yogis of all don’t just cheat death, they deal it too. They can simply look at a man and he’ll drop dead. Minus his heart. Meanwhile, a yogi who has renounced speech and food but manages to make coconuts materialise out of thin air is obviously a Muslim in disguise. Battuta can’t get enough of those guys (he’s a bit suspicious of the girls, however, claiming that they’re the ones who tend to specialise in the death dealing, heart-stealing business). Almost six centuries later, neither could novelist Thea von Harbou and her husband, and screenwriting collaborator, the celebrated director Fritz Lang.

While von Harbou and Lang are best known for collaborating on the German Expressionist classic Metropolis (1927), which is based on the former’s novel, they met and began what was then an affair during an earlier cinematic adaptation of one of her works, The Indian Tomb (written in 1918). That adaptation ended up being the basis of a four-hour, two-part silent movie, directed by Joe May (once he had kicked Lang out of the director’s chair) and released in 1921. Having been largely forgotten until the latter part of the twentieth century, it is now rereleased in a centenary edition. And it begins with a yogi being dug out of his hole in the ground.

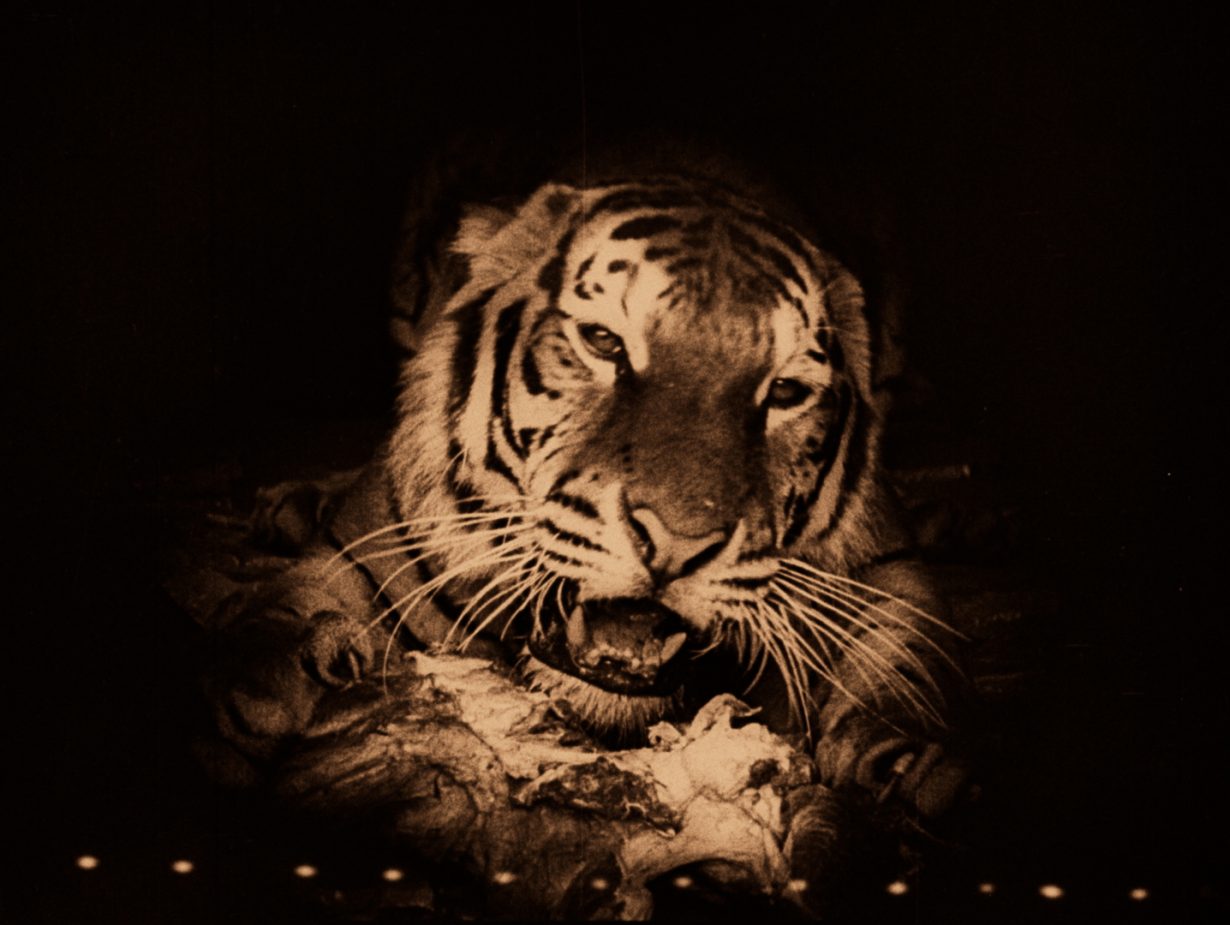

With its cast of browned-up Germans and a Hindu iconography that seems to incorporate aspects of Buddhism and Islam, with costume that fuses aspects of the Near and Far East (it’s like the movie was shot inside the V&A or British Museum), with gargantuan yet strangely spartan temple sets, ceremonial elephants, man-eating tigers, erotic dances and the odd snake in a basket, you don’t need me to tell you that the film is ‘rich in exotic mysticism’ (as its distributors do). Of course, you might equally figure that as crude orientalism; or, if you’re inclined another way, as merely reflecting the European attitude and world-view of the times. Where the Indian prince digs up a yogi when he wants to know how to get something done, his European counterparts (we’ll come to the characters later) consult an engraving, or one of their friends’ libraries. When the European gets to India, he strides out on a clifftop looking across the valley in the manner of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1817); meanwhile the Indians live in a fog of temple incense and hookahs. But let’s not question von Harbou’s commitment to Indian studies: her marriage to Lang would later end shortly after he (himself a serial philanderer) caught her in bed with an Indian student 17 years her junior (she went on to marry him in 1933, secretly, because the Nazi Party wasn’t into dark-skinned men).

Still, you’ll be wanting to know about The Indian Tomb’s plot. By some sort of rule of the undead, the yogi is bound to serve the person who dug them up. In the case of this film that’s the Indian prince. In order to save himself some time and trouble, the prince makes the yogi magic himself over to somewhere that might be Germany or Britain in order to persuade (by trickery if necessary) the German or British architect Herbert Rowland to build a tomb for the prince’s one true love. Rowland himself has been fantasising about building a grander and more beautiful mausoleum than the Taj Mahal, an engraving of which he stares longingly at. He’s got a fiancée too. But she’s not important now. Professional desires come first. Rowland has to leave immediately to begin work on his dream job. This time the yogi and the architect travel by car and by yacht. Presumably because the yogi is using all his magic to make sure that the fiancée doesn’t reach, speak to or hear from Rowland before he has been willingly spirited away to India. It’s unclear why, other than to enforce the Faustian nature of the architect-prince bargain, such secrecy is necessary, but later it will be explained that Rowland needs to ditch his European attachments (fiancée included) in order that he might absorb ‘the blood and soul’ of India to make his tomb the most magnificent in the world. Which seems reasonable enough (although the architecture of the Indian sets featured in the film, somewhat Angkor Wat-like in detail and scale, would suggest that, when it came to magnificence, a local architect would have been a better bet). Rowland then finds out that the tomb

is going to house a princess who’s alive rather than dead. Although she might be soon because the prince is determined to have his revenge on her for having an affair with an Englishman. The prince has a pit of tigers in case he needs to dispose of someone; the Englishman likes disposing of tigers for sport. Rowland’s not sure what to do. Meanwhile his fiancée manages to track him down to the prince’s palace. She and Rowland are nevertheless kept apart. Prisoners at either ends of the palace. Rowland catches leprosy while looking for her and wandering into the prince’s leper colony-cum-torture chamber. Later, he’ll be cured by the yogi. Who, himself, will slowly morph from a ghoulish, zombielike henchman to an embodiment of the prince’s conscience. Before disappearing into thin air. The Englishman will be fed to the tigers. It won’t end well for the princess either. But I don’t want to spoil it for you.

Perhaps what comes across most strongly when watching The Indian Tomb is not the extent to which it is a product of its time, but the extent to which, as much as it’s the product of all places, it’s the product of all times – 1341 (that’s when Battuta was running away from the Sultan of Delhi and into the arms of the infidel bandits), 1818, 1921… And hey, let’s not leave ourselves out of all this, we’re the ones to whom this is being marketed as an exotic cultural treat. Even Lego’s token ‘Indian’ figure (the Eastern kind of Indian, not the one whose accessories include a tomahawk, a headdress and a squaw) comes with turban, a snake and a pipe.