Richard Bosman’s cinematic paintings confront the life of the artist, a turbulent melodrama beset with danger and instability

I’m Canadian. Like all Canadians I was raised on American entertainment media. I watched American news. I watched American television. I watched American movies. American media both entertained and educated me, showed me what the world was and how to live within it.

America, in many ways, is my very favourite movie. It’s a multi-genre epic, with a particular talent for depicting action, comedy, romance and horror.

When I first encountered Richard Bosman’s work, it seemed as if I’d found an artist whose paintings were the storyboard for this most incredible of films; someone who understood just how noir America is, with its historical cast of sleazy characters, cynical scenarios and emphasis on personal over communal prosperity. Or at least that’s how some psychogeographic component of Canada, crippled by both an inferiority and superiority complex, characterises our southern neighbours, whom we’re both fascinated by and judgemental of.

Many immigrants to North America learn English by watching soap operas. Soap operas compress language into its most fundamental, juicy elements, by using melodrama to tell personal and dynastic stories. When learning a new language, words related to survival are the ones you must grasp first; words like danger, love, help, fire, police and emergency; all components of a noir, melodramatic vocabulary.

Bosman was born in 1944, in Chennai, India, was raised in Egypt and Australia, and settled in the United States in 1969. This information, when I received it, was instructive, and makes further sense after you learn that much of Bosman’s early work was inspired by, and based on appropriated images from, Hong Kong comic books from New York’s Chinatown: detective stories, and tales of the fictional Judge Dee, a magistrate from the Tang Dynasty. In this way Bosman is operating within a Möbius strip of translation and language acquisition by way of motifs and types imbued with drama, action and romance. It reminded me of how my Chinese doctor in Vancouver learned English by watching the classic American soap opera As the World Turns (1956–2010).

In an email exchange, Bosman cited noir films and the works of Joseph Conrad as further inspiration. Early on, he introduced into his paintings a character called The Blind Detective, who is literally that: a gumshoe in a trench coat, replete with dark glasses, a cane and a pistol, attempting, somewhat haplessly, to solve crimes he’s clearly ill-equipped to investigate. In The Stabbing of The Blind Detective (1981), Bosman’s hero points his gun at a handcuffed, blindfolded woman, unaware he’s about to be knifed in the back by a sinister hand intruding on the leftward edge of the canvas. In The Blind Detective in the Hall of Mirrors (2012), the protagonist, pistol and cane at the ready, is confronted by seven reflections of himself, none of which he can see, ostensibly trying to catch a criminal he’s simply outmatched by. In The Blind Detective on Thin Ice (2012), the same figure walks across a frozen pond, directly towards a sign cautioning him to cease walking, which he of course cannot see. Beyond being beautifully painted – Bosman’s seemingly casual, expressive brushwork belies a deep aptitude for realism – these paintings are funny while also being poignant and sad.

Over the course of his career Bosman would move from a faux-naive style into a more loosely rendered, realist figuration. His themes, in turn, migrated away from crime (or piled further hardships on top of crime) but not from calamity and disaster. One series of paintings presents the interior of a car, the rearview mirror the central point of the image, often showing the driver holding a gun, or engaged in other crime-related or life-and-death scenarios. This sort of perspective is only ever seen elsewhere in film, and film motifs have indeed become increasingly apparent in Bosman’s work.

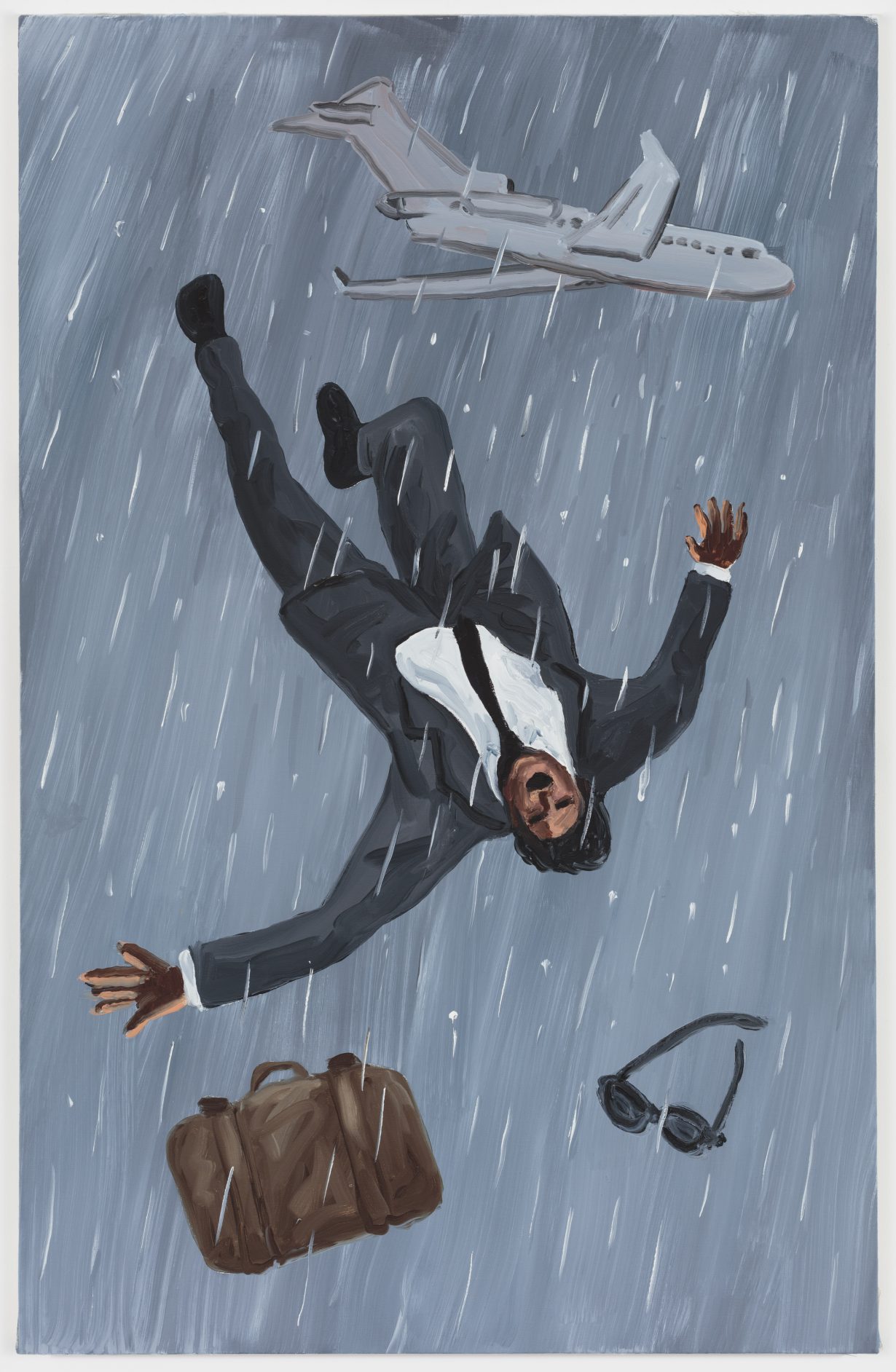

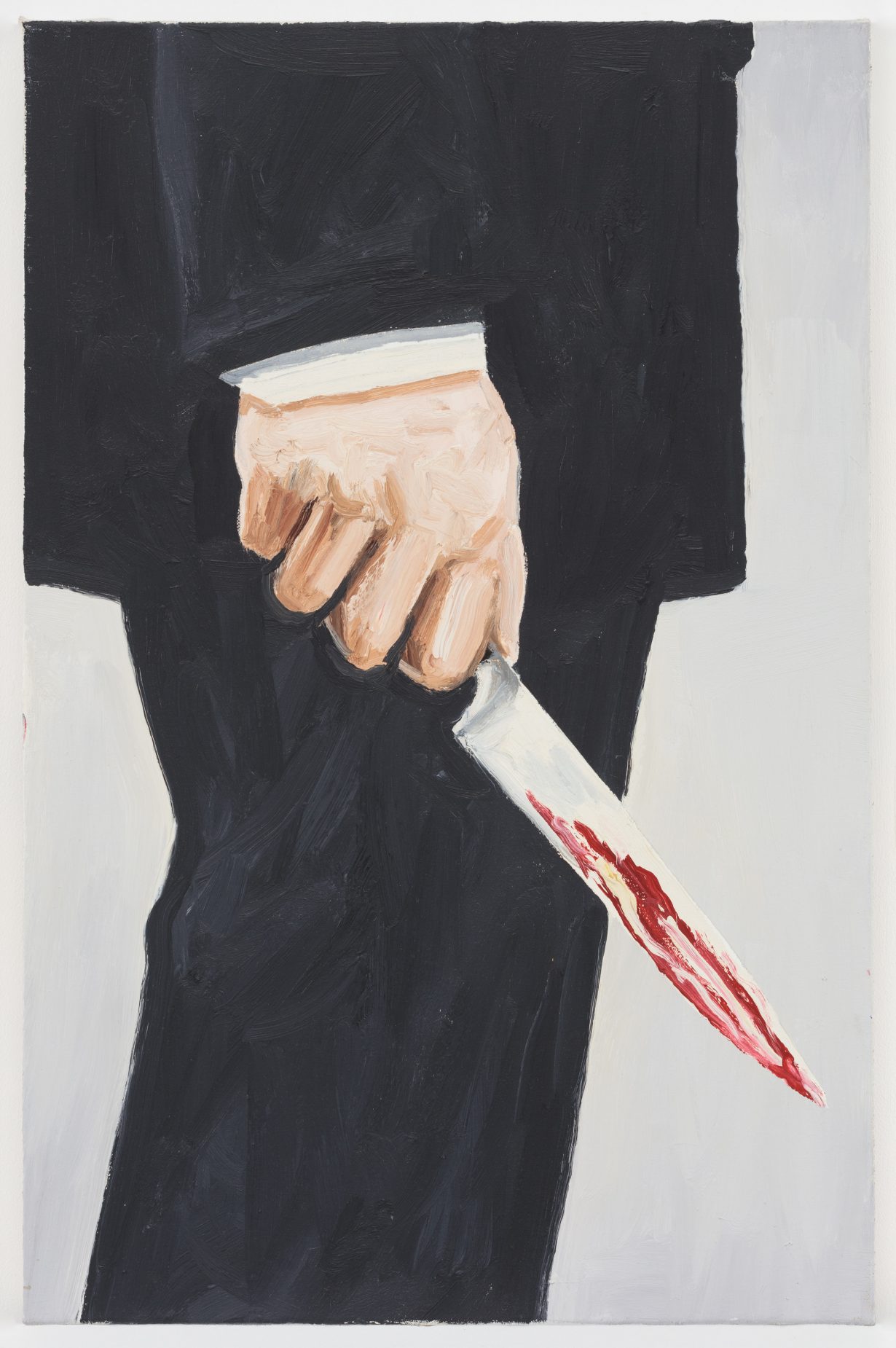

Over the last two decades, not only film but the sea disasters of Conrad’s stories, and notions of man versus nature (and domesticity), have also increasingly informed his paintings and prints. A sampling of the range: DB Cooper’s Gamble (2019) depicts the famed skyjacking bank robber plummeting through the sky, away from the plane he’s just leapt from. Knife (2015) is a beautifully composed, somewhat Taishō-era-Japanese-print painting of the central third of a man in a business suit, grasping a bloody knife in his right hand. Bad Kitty (2019) is a woodcut print of a woman’s hands, holding aloft a black cat whose paws are dripping with blood. Dryer Fire (2017) is a monotype of a frightening domestic scene, wherein a clothes dryer has burst into flames. Similarly in Oven Fire of that same year, an oven is engulfed in flames.

Bosman, as the tabulation above might suggest, paints many subjects, many scenes and many moods, but those that seem absent from his body of work are peace of mind, serenity, safety and relaxation. In this way, informed perhaps by the fact that I myself make and exhibit paintings, I’ve come to view his work as all related to the life of the artist. People cling to boats in rough water; figures grasp at branches on the sides of cliffs; they, like The Blind Detective, stumble around in a world of confusion, searching for meaning and safety. The life of the artist is a turbulent one, beset with danger and instability. The human battle to conquer, or survive, the elements is not dissimilar to the artist’s battle to conquer, or survive, an encounter with a blank canvas. Bosman has made multiple paintings of people climbing out of crashed cars in snowstorms, and while it may seem melodramatic, there’s a certain relatability there; artmaking can sometimes feel like trying to make sense of, and recover from, an unexpected disaster. By using these melodramatic motifs and campy portrayals of life lived on the margins, he is, in a way, just painting the biography of a working artist.

This connection in turn is made clear, and beautiful, by the selection of works in Bosman’s summer show at New York’s Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, guest-curated by Matthew Higgs, the long-standing director of White Columns. Spanning the years 2009 to 2016, the 19 paintings in the exhibition are explicitly all about other artists: depictions of their studios, their living quarters and their ‘doors’; paintings of doors named after artists, standard doors seen in homes that look as if they’ve been painted by the artists whose names are attached to them in the titles. So Yves Klein Door (2016) is door-sized (183 × 81 cm) and depicts exactingly the handprints, breast- and belly marks familiar from Klein’s famous Anthropometry (1958–62) paintings. Piet Mondrian Door (2016) is angular and austere, while Basquiat Door (2016) replicates the telltale crossed-out text and scrawled bright colours of the artist’s paintings. The paintings are at once great trompe l’oeils, homage and a beautiful way for an artist to experience what it may have been like to work like an artist whose work they admire.

What painter doesn’t want, at some point, to try making a Barnett Newman painting? Bosman permits himself to do so in Barnett Newman Studio (2010–11). The left side of the slim vertical painting depicts a fan, stool and telephone in the artist’s studio; the right depicts a zip painting in progress. Rothko’s Studio (2011) is an almost photoreal painting of a ladder and the putative back of a Rothko painting (the back of a painting being a somewhat mystic concern among painters), while two other canvases in the exhibition plainly just depict the backs of paintings themselves: one a Marsden Hartley and the other unattributed, both beautiful ways to deal with abstraction and the occulted. Filling out the show, meanwhile, are paintings of James Ensor and Philip Guston’s studios; whether they’re based on fact or imagination doesn’t matter.

Slipping into someone else’s shoes might, in the circumstances of Bosman’s practice, constitute a kind of relief, or it might be another form of conflict. Probably the latter, for having only discovered his work five years ago, and having exhibited paintings myself for close to 25 of my 48 years, what I find most compelling in his pictures is the sense of unrelenting struggle. This resonates in a deep, psychic and physiological sense – the blank canvas as adversary, the career as monumental pugilism. All told, Bosman seems criminally under-known. Hopefully this new exhibition will shine a light on his work, and validate that which he’s depicted so poetically, and humorously, over these many decades; man’s almost unceasing struggle to combat anything and everything: from crime to climate, kitchenware to contemporary life.