A series of upcoming biennials promise to explore the art of the ‘Global South’. But what does that mean? And is the term of any practical use?

The first Bienal de São Paulo, in 1951, was the product of the USA’s dominance in the postwar world. It was organised by the Museum of Modern Art São Paulo (MAMSP), the institution itself founded just five years earlier by industrialist Ciccillo Matarazzo in close conversation with his friend Nelson Rockefeller. The latter, by then heading a cultural division of the American government, and with close ties to the CIA, had already helped fill MAMSP with work by artists labelled ‘new Americans’ and ‘Europeans in Exile’. The biennial was Matarazzo and Rockefeller’s next big soft-power project aimed squarely against the spectre of communism.

Over 70 years later, the 35th edition of the Bienal promises to be an altogether different affair, looking instead, the curators say, to artists from the ‘Global South’. In that, the Bienal curators are not alone: Videobrasil, a biennial survey of (primarily) moving image, which will open in October, has used the term in its artist-selection criteria since the São Paulo-based festival’s inception, in 1991. Raphael Fonseca, who is cocurating Videobrasil, calls the Global South “a fictional idea of community, knowledge and creators that can contrast with the hegemonic North”, useful even in its construction.

Similarly loose definitions promise to be present too in next year’s Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa under the title Foreigners Everywhere, which, the Brazilian says, will focus on artists ‘who are themselves foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, and refugees – especially those who have moved between the Global South and the Global North’. Weaving around September’s and October’s institutional offerings in São Paulo is a festival of kizomba music. Organised by musician and writer Kalaf Epalanga and artist Nástio Mosquito, the festival celebrates a genre born of south-to-south exchange from Angola and the migrant bairros of Lisbon to Brazil and then back again.

The definition of ‘Global South’ is a historically shifting one. First coined during the late 1960s, it maps out an anticolonial history as much as a geography. In the prewar period, first Aimé Césaire and then Frantz Fanon argued that the pan-continental extractivism and violence of European imperialism needed a continental response, offering négritude – an expression of revolutionary Blackness, a ‘colossal mass’ of people power that ignored borders but shared a political consciousness – as an answer. Moving forward, in the midst of the Cold War, the 1955 Bandung Conference of mostly newly independent Asian and African countries, as well as the subsequent formation of the Non-Aligned Movement three years later, ignited by postcolonial nationalism, imagined cooperation beyond racial lines in the face of encroaching imperialism from both the US and the Soviet Union. The more contemporary image of the Global South – with a cartography that features Africa; South and Central America and the Caribbean; Asia without Israel, Japan and South Korea; and Oceania without Australia and New Zealand – is more active in the fields of economics and culture.

On the one hand it is neoliberal in outlook, in that its economic traction can be found in arrangements such as China and Brazil’s deal (this past March) enabling mutual trade and investment directly through the local currencies instead of using the US dollar. (“Every night I ask myself why all countries are obliged to do their trade backed by the dollar. Why can’t we do our trade backed by our currency?… Who decided it was the dollar, after gold as a parity disappeared?” Brazil’s President Lula asked a meeting of the BRICS countries.) Yet many people are as likely to meet the term within the cultural sphere, with curators keen to harness its radical sheen as a cartography in which, as the Indian historian Vijay Prashad articulates in his 2012 book The Poorer Nations, a ‘concatenation of protests against neoliberalism’ could take place. A place in which disparate fights might conjoin to common revolution.

The sea change is generational, says Fonseca. “Older generations – the ones of institutionalised agents, especially in the 80s, 90s and even 2000s – mostly came from privileged classes. These were those who were able to study abroad, move to Europe and the US, and play essential power roles in the global art system. It is fascinating to notice how, in the last ten years, younger agents from underprivileged backgrounds – myself included – were able to expand their reach from within the Global South and outwards from it. Many reasons for this can be listed here: a more significant connection between different agents through social media, social movements that made institutions reshape their goals, leftwing governments that supported more education.”

A four-person collective (with no chief curator), the members of which – Manuel Borja-Villel, Grada Kilomba, Diane Lima and Hélio Menezes – had barely met prior to their appointment, is in charge of the current Bienal de São Paulo. Menezes, who trained as an anthropologist before moving to curating, says their taking the reins (the first time any Black curators have taken control of the 72-year-old event) is “an opportunity to create something new, to overcome those hierarchical and often violent ways of working that are so familiar”. One quiet innovation was to refuse to provide nationalities for the 120 artists taking part in the show in preview material.

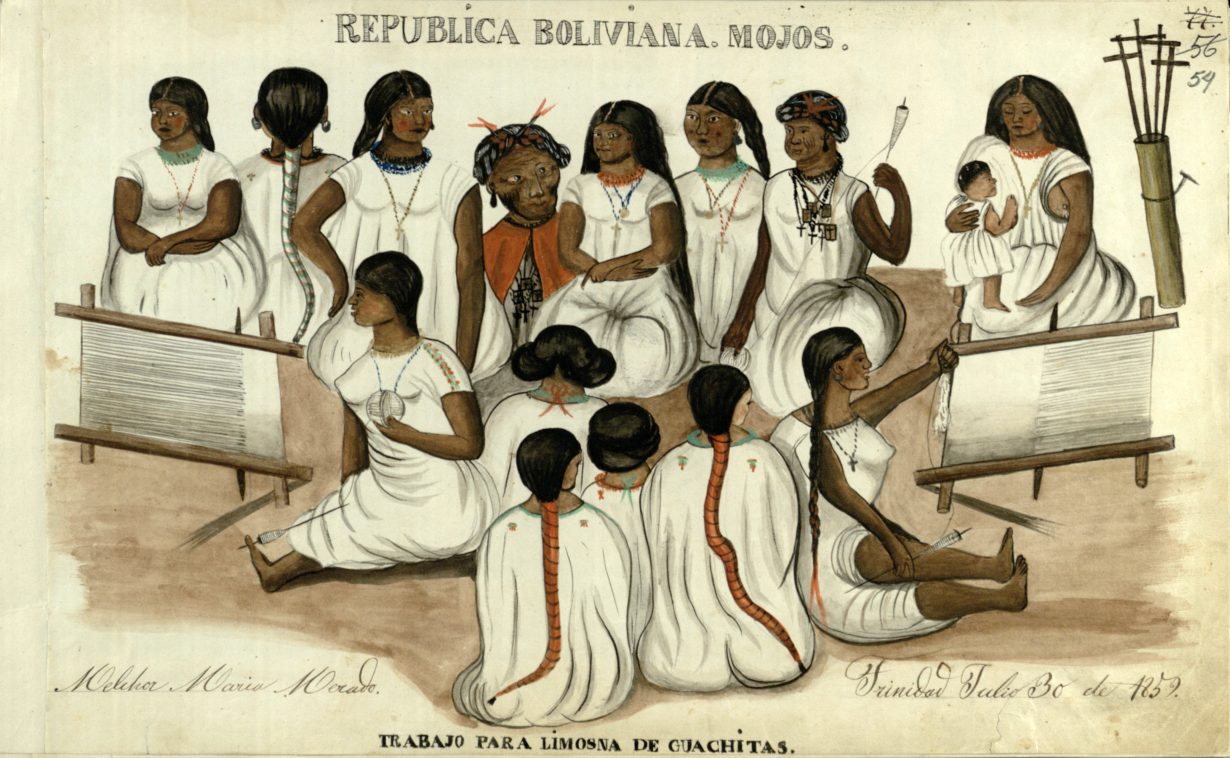

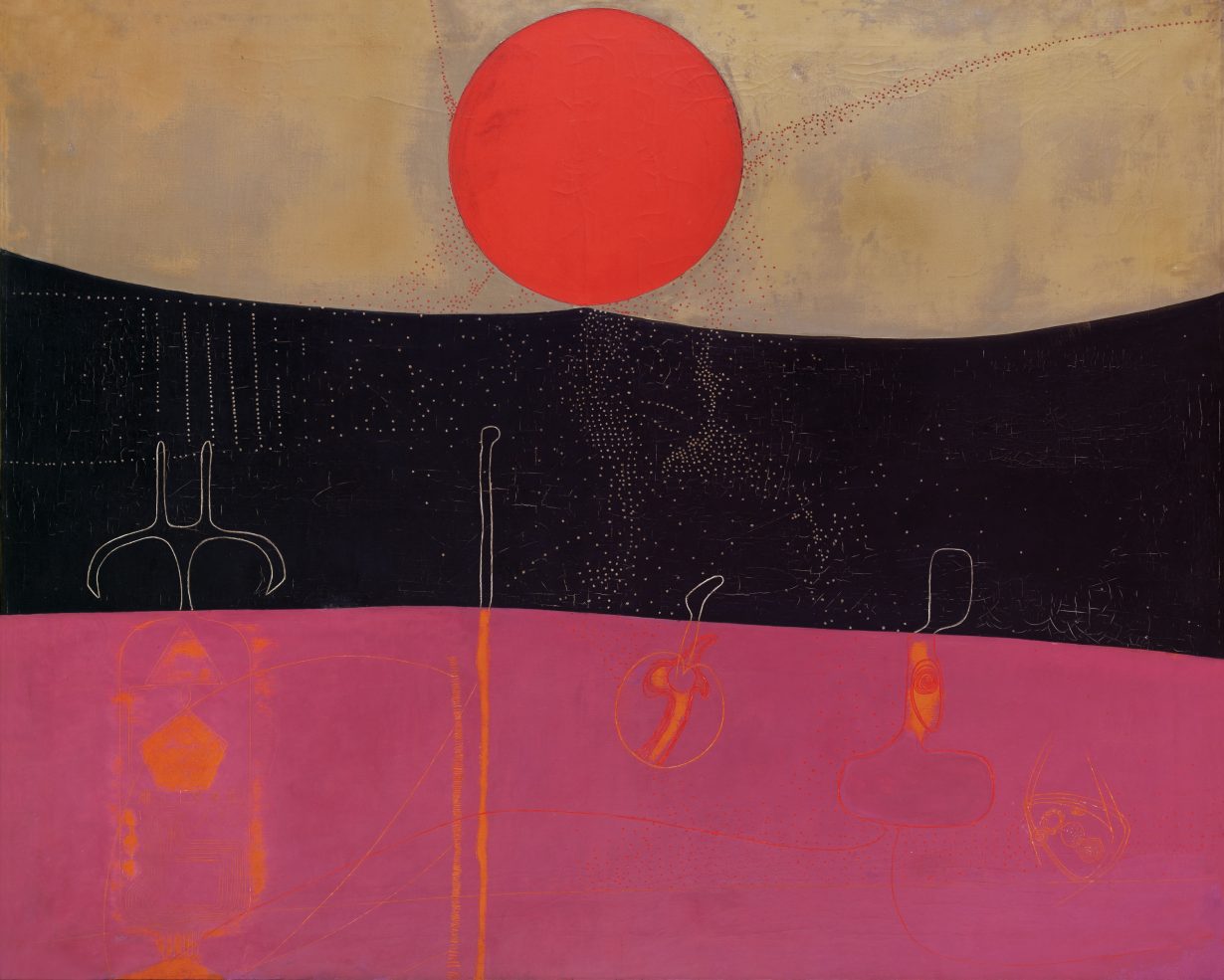

“Are the biennials there to confirm a structure that always existed?” Kilomba, who is an artist, replies when asked about this. “Or is a biennial there to break its own history, there to think anew? One of the categories that biennials are constructed around is nationality. And countries are very keen on being represented.” Indeed, until 1981 the Bienal was ordered around national pavilions, a structure the Venice Biennale maintains. “But what is the most important aspect of an exhibition? Is it the artist? Is it artistic practice or the artwork? Or is it a representation of a country? And what country is that, when we are talking about and working with artists that do not necessarily have a country, or the country they were born in no longer exists? How many countries do I have, or how many countries does Hélio have? Where do you place an artist who is indigenous and has multiple territories or their territory is not defined as a nation and a flag?” The notion of the Global South can therefore provide some unity amidst a show whose participants range from an archival photography collective from Bahía to Colectivo Ayllu, a Spain-based South American trans group who seek to make ‘visible what Euromodernity seeks to erase’. The artworks, Menezes says, once installed in Oscar Niemeyer’s 1954 modernist pavilion, which is named after founder Matarazzo, “will become fugitives from the building itself ”.

“We have objects, these are the facts of the show, and they talk. And very often they talk in ways you don’t expect,” Borja-Villel agrees. For the former director of the Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Global South is an attempt at thinking outside the parameters of the art canon historically established on the European and North American axis. It allows a way “to reject European or Western universalism. Many of the artists we are dealing with, for example the Mayan artists in Guatemala or the south of Mexico, in their languages they don’t even have a term for art. That doesn’t mean they don’t have artistic practices; it means their artistic practice is mixed up with religion and is mixed up with ecology.”

In his day job as the director of Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP), Pedrosa has been forging similar links recently, welcoming non-Brazilian artists who might have some affinity with a more plural understanding of Brazilian identity. Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe, a Yanomami Venezuelan artist, is currently showing, and Brook Andrew, an indigenous Australian, is opening an exhibition at the institution in September. It’s a sign of progress, but there’s more to be done in a country that rarely registers the outside world: a sign, perhaps, that for the signalling of big, occasional art events, the idea of day-to-day postnational Global South identity is a fantasy. “Brazil is still a very self-centred country,” Fonseca says. “Of course, it has to do with the financial opportunities art agents have, but it is also historical and existential. You need to look at how many projects in Brazil pay attention to the idea of Latin America – very few. If we have this distant relationship with our neighbours, what can we say about geographical art scenes that have lots of shared histories with us – like, for example, Southeast Asia – but are generally forgotten in Brazil?”

Epalanga was inspired to stage the kizomba festival in Brazil because he too was concerned that there was a lack of interest in the country’s cultural entanglements beyond its borders. In his 2017 novel Whites Can Dance Too, recently translated into English, Epalanga describes a house party of Lusophone immigrants in Lisbon. As the Angolan writer’s characters put records on, dance and flirt, their conversation turns to the overlaps and divergences of music from Brazil’s northeast and that from Africa. They discuss kizomba; how Cape Verdean morna music gave rise to its more energetic cousin koladera, the faster tempo of which is influenced by Brazilian samba and Cuban bolero, genres with a base of African – particularly Angolan – DNA, born of the slave trade and massive forced migration. The musician and writer says Brazilian domestic politics, of a type that date back to Rockefeller’s original diplomatic meddling, “but which was taken to another level by [far-right former president] Bolsonaro in modern times” have played a part in this musical estrangement. “It’s a fear of communism. We forget that Portuguese-speaking Africa was part of the Soviet crew, and Cuba played a role as well. Brazil’s power structure is paranoid about that.” He warns that while ‘Global South’ must be “used with an awareness of its limitations, considering the diverse and unique characteristics of the individual countries it depicts”, it is nonetheless “useful in recognising shared experiences among countries with similar historical and economic backgrounds, reflecting the postcolonial challenges and fostering solidarity.” As ill-defined as the term might be, in the cultural sphere the real value of the Global South is to open a space for decolonising conversations, articulating the kind of hybridity and complexity of modern identity that a nationality cannot, a conversation held far from the old imperialist orders of the Northern hemisphere. A utopian geography that may never be real but can serve a purpose.

The 35th Bienal de São Paulo takes place at the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion from 6 September to 10 December. The 22nd Biennial Sesc Videobrasil is on show in São Paulo from 18 October to 25 February. The Venice Biennale 2024 is on show from 20 April to 24 November