‘You know you’ll feel better after doing it, but still you don’t start’

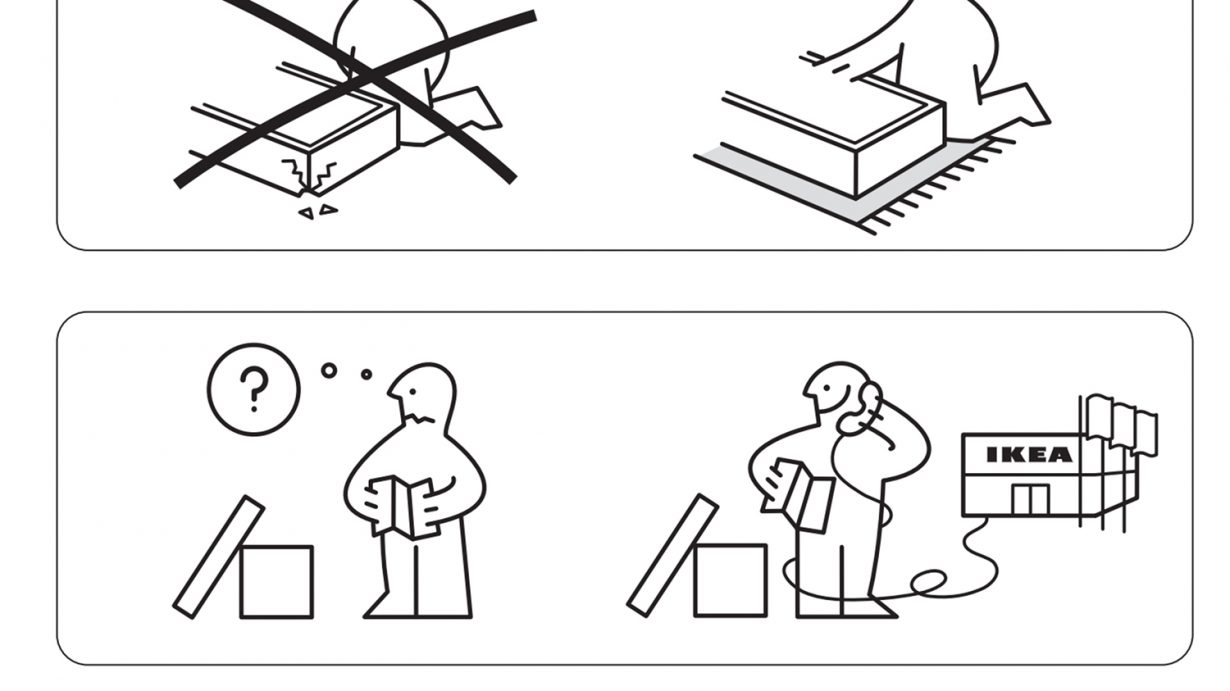

It’s midmorning on a weekday and, because I don’t have a proper job and I’m putting off writing something, I’m kneeling on the patio and assembling some flat-packed furniture. Over the gentle clockwork resolutions of a Spotify baroque playlist – to repurpose a meme, if you construct kitchen cupboards according to instructions while listening to Bach partitas, your body takes a screenshot – I can hear my octogenarian neighbour pushing his petrol-powered mower around for the third time this week. Down the road, other elderly locals are similarly manicuring their gardens, which is to say that, at least in part, they’re imposing order on the unruliness of nature. It makes sense that this activity seems to appeal more as life shortens and the body mutinies and degrades (“Gardening creeps up on you,” my father used to say); in its controllability and fixed borders, it’s a bulwark against encroaching anxiety. But then so is putting together furniture according to diagrams, which might, in turn, be construed as the absolute inverse of writing about art, and especially writing about art in this benighted summer.

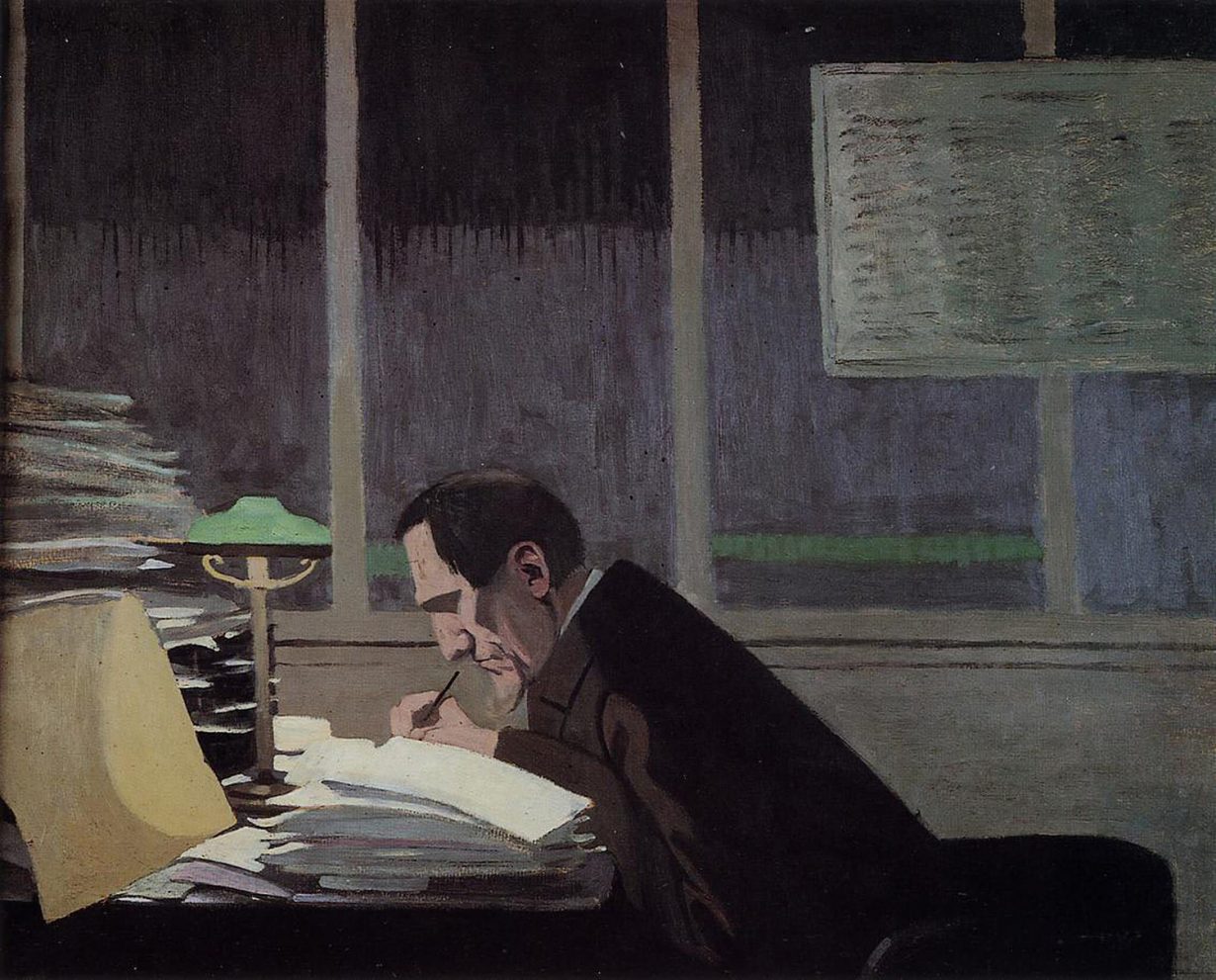

When I taught a critical writing course a couple of years ago, I had to sit down and ask myself how I write. You don’t necessarily want to say to aspiring critics that writing is the endpoint of extended periods of low-level anxiety, pacing around, procrastinating and thinking you’ve got nothing, no thoughts of worth, but in a quarter-century of trying I somehow haven’t found an easier way. Even writers who are meticulously organised don’t fully escape it; in his collection of essays on writing, Draft No. 4 (2017), the veteran nonfiction author John McPhee describes his intricate, filecard-heavy method of structuring essays and books, but he also mentions episodes of total paralysing confusion and panic. And McPhee operates in the realm of verifiable facts. I’m futzing with furniture partly in order to have a liveable home but also because shortly I have to write something about a group of paintings I’ve seen and, as usual, all I’ve got is a vague knot in my solar plexus that contains, or constitutes, the opinions on them that I don’t yet know. When the language of articulation, of which at this moment I’m convinced I possess none, is in tune with the feeling then the work is pretty much done. (This text, obviously, is not an advertisement for any future writing course I might teach.)

To judge from the fact that most of the writers and critics I follow on Twitter spend a lot of time tragicomically lamenting that they’re not getting on with it, or occasionally say things like ‘not writing is writing too’, some kind of uncertainty phase is necessary; it’s when most of the decisions are made, even if you’re not noticing. But it also grates on the nerves. One can’t spend all one’s time in a condition of not-knowing or recovering, to put it dramatically, from a process of clarification, aka typing. ‘How do I know what I think until I see what I say?’, E.M. Forster famously said, a quote that elides the gnarly period when you know you’ve got to say something but you don’t know what, and that, in the case of art criticism, is compounded by the fact that there’s no right or wrong.

On a higher level that’s true of art and literature too, which is why it’s notable that you often see creative practitioners creating a counter-world of definite parameters in their lives. Haruki Murakami describes his morning writing practice as an utterly wayward thing, like a waking dream, and then ritually runs 10 kilometres every afternoon. Figures from Lucien Freud to David Lynch to Patricia Highsmith are known to have eaten the same thing every day. Painter friends of mine, I’ve noticed, tend to soundtrack their studio explorations with the snap-to-grid precision of techno or the perpetual resolutions of sixteenth-century classical music. And, in fact, this creation of an oasis of certitude doesn’t need a creative counterpoint; sometimes life demands it. (In 2017, in the wake of Trump’s election, Gary Shtyngart and Jia Tolentino wrote New Yorker essays about using, respectively, high-end watches and skincare regimes as coping mechanisms.)

Critical writing is not an art; it’s a craft, I think. But it has its own minor existential contours: not least the factor of responding intuitively to something that frequently was made intuitively, the worry that you won’t understand new art and will have to trawl museum shows until you expire, or that you’ll be replaced by an AI before that happens, or that criticism will enter a terminal crisis of irrelevance. Plus, at a moment of omnidirectional real-world disasters and given the internal contradictions of the artworld, sentence-making about paintings, etc might well feel a bit frivolous, an indulgence.

Yet it’s also a form of ersatz gardening, a physiological method of creating order, structure, form, even if only provisionally so; of learning to live with tension and temporarily get past it, getting into trouble and getting out of it. There’s a murky blur of something, a residue of experience – of looking – which needs excavating and cleaning up and turning into language capped with a final full stop. You know you’ll feel better after doing it, but still you don’t start because, on some level, you think you’re about to demonstrate to yourself that you can’t, in fact, do it anymore. Then you do it and in the process find out something of what you think – about, for instance, the Sisyphean plight and subconscious defence strategies of the jobbing critic. Shortly after, if you’re lucky, the process starts all over again. In the meantime, those cabinets won’t build themselves.