The unspoken presupposition that artistic value is conferred by the establishment seems at odds with the artwork

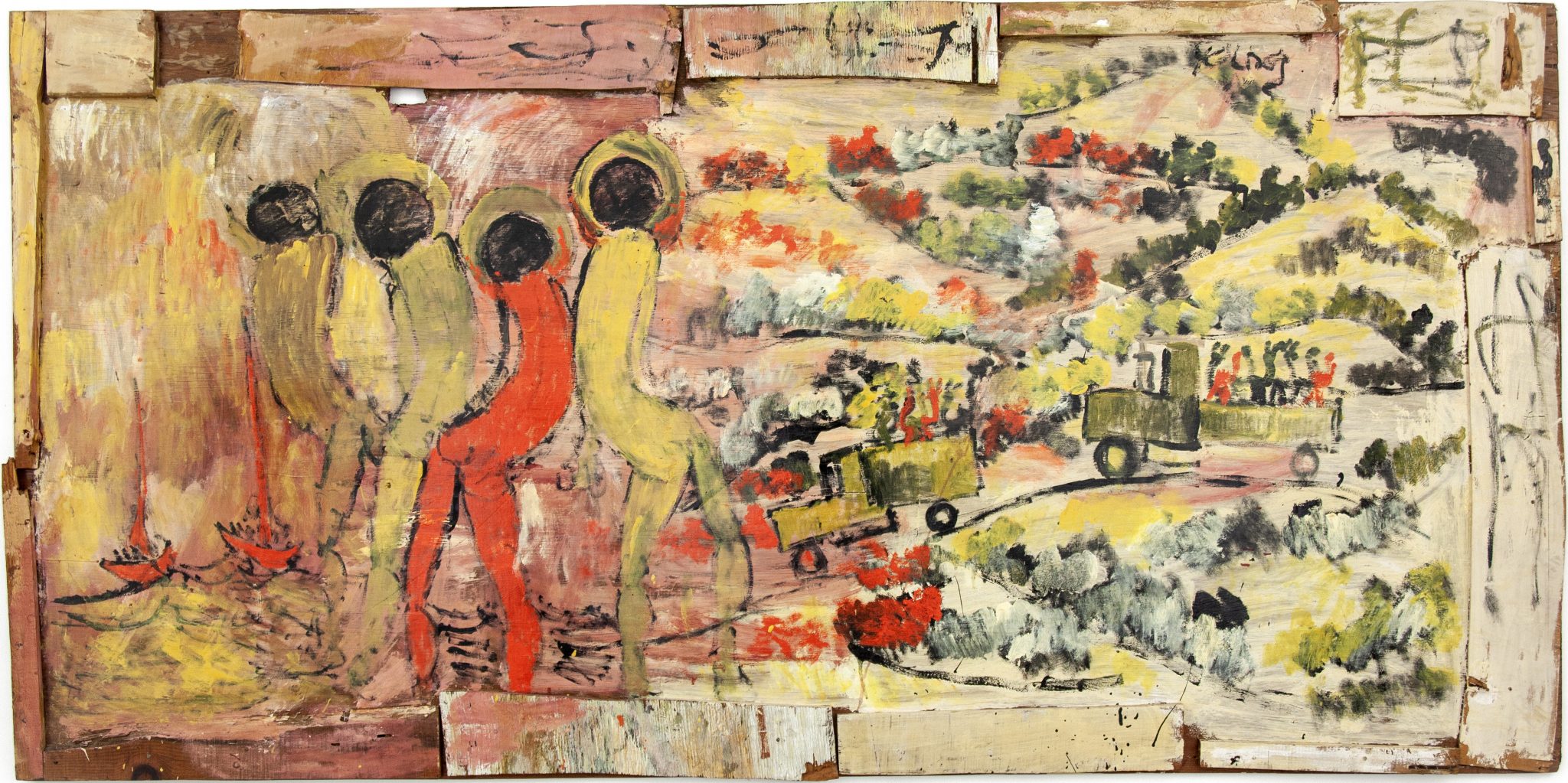

When Ronald Lockett told his uncle Thornton Dial that he wanted to go to art school, Dial did not mince his words. ‘He told me I had the best school of all just making artwork,’ Lockett recalled in 1997. ‘He helped me to find out that you could take tin or barbed wire or different small little metals and make things out of them.’ Dial became Lockett’s artistic mentor – and for his own complex and compelling assemblages, Dial, in turn, had drawn on traditions that were not taught in formal institutions: the yard shows of the American South; African wood-carving; the gospel church. The subjects these artists took on – from slavery and Jim Crow to more immediate racial oppression in the American South – were likewise rarely represented in more formal channels. Now, their work is on show at one of the most august art institutions in the world: the Royal Academy of Arts in London. And you can’t help but wonder what they might make of it.

Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers: Black Artists from the American South is the latest chapter of a decades-long project by the late Georgia-based collector William Arnett to establish the work of these artists – whose work Arnett called ‘the one great thing America has ever had to give to the history of visual arts’ – in the great museums of the world. In recent years, the Souls Grown Deep Foundation (the title comes from a poem by Langston Hughes) has transferred much of Arnett’s 1,300-strong collection to institutions across the United States and abroad. Major acquisitions have been made, to date, by 34 museums, beginning with the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2011 and including the Met and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Now, a select group of the works remaining to the Foundation – as well as a small number of loans from elsewhere – have temporarily made their way across the Atlantic.

On the strength of the RA show, it’s hard to disagree with Arnett’s oft-repeated assertion that these artists are every bit the equal of Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns. In fact, I’m put in mind of Rauschenberg from the get-go: the first thing that confronts visitors is a lion’s head, its pelt of black carpet with daubs of white enamel for markings, mouth agape in a frozen roar. The body it is attached to is a curious assemblage, with armatures of a table and chair welded together and hung with chains; a bottle of spirits is fastened midway down its torso. This is King of the Jungle (1990) by Thornton Dial Jr (son of Thornton Dial Sr), a work of considerable, if inscrutable power. It’s impossible not to think of Rauschenberg’s Monogram (1955–59), perhaps the most famous of his Combines besides his Bed (1955): a stuffed goat with a car tire around its midriff.

In a sense, the comparison is apt: Rauschenberg said that part of the inspiration for his Combines came from visits to the yard shows of the American South. But it is also uneasy: much of the disruptive force of the white artist’s work came from the knowing elision of distinctions between the historically separate categories of painting and sculpture, and the introduction of the resultant constructions into the gallery space. The majority of the works here were made, instead, to be displayed on porches and in front yards, serving as an expression of creativity that had little regard for the idea of distinguishing painting from sculpture in the first place, and that was above all for the benefit of the community.

All of which makes some of the curatorial choices here a little jarring. A pared-back, even a purist approach has been adopted. There is very little by way of wall text in this show, or other contextual information, save a brief video detailing the vast installations of Joe Minter in his front yard in Birmingham, Alabama, through which he is wont to lead visitors with a talking stick, adorned with trinkets. The walls and plinths are uniformly white, or a dull grey. It’s as though the curators are at pains to make plain that these artists belong here. But the unspoken presupposition here is that artistic value is conferred by the establishment – and that seems powerfully at odds with the message conveyed in many of the actual works. Richard Dial’s Which Prayer Ended Slavery (1988), a mass of welded steel in which abbreviated figures are flayed, hanged and held in chains, is a work of skilful execution and visceral energy. An assemblage such as Lonnie Holley’s Keeping a Record of It (Harmful Music) (1986), a horse’s skull stuck to a broken record, is the result of great wit and conceptual daring, while also reflecting on the ways in which Black music has historically been deemed dangerous. These works can certainly stand their ground in these surroundings. But do the surroundings actually serve this art all that well?

In a note ‘On Language’, published on the Souls Grown Deep Foundation website, it is proclaimed that the foundation ‘abjures’ the terms ‘outsider’, ‘self-taught’ and ‘visionary’ on the grounds that their application to these artists, given the circumstances that denied them the opportunities afforded to others, is racist. This seems entirely right and good – but there is nonetheless a risk, in going to such lengths to shield them from these labels, of veering too far in the other direction. In her catalogue essay, curator Raina Lampkins-Fielder asserts that the Gee’s Bend Quilters created ‘some of the most visually compelling and contextually profound works of abstract art in any tradition’. Certainly, the geometric patterns realised by Annie Mae Young, Loretta Pettway, Mary Lee Bendolph and many more, through improvisation with stray strips of cloth, demonstrate a thrilling aesthetic freedom. But can they really be said to have been participating in a tradition of ‘abstract art’? One thinks of Hilma af Klint, the Swedish mystic who is often nowadays touted as having beaten Kandinsky to the mark in inventing abstract art. What af Klint was doing, and what the Gee’s Bend makers were doing, had its own logic, its own systems of meaning, which the description of ‘abstract’ – an attempt to retrofit the narrative of art history handed down to us from the twentieth century – fails to encompass.

Of the art historian’s role, Michael Baxandall once wrote that ‘we do not explain pictures: we explain remarks about pictures’. It’s a phrase that stays with me throughout this show. Here, more than ever, the established vocabulary of art history seems lacking. High on the wall of the first room hangs a work by Mary T. Smith from the early 1980s. A crowd of adumbrated faces, painted on a long strip of corrugated tin, are accompanied by the slogan: ‘We all Want a Jobe’. This is what is given as the title, on the wall label and in the catalogue, except that in both cases it is accompanied by the words ‘We All Want A Job’ (my italics), in square brackets. It’s a tiny detail, but it feels unfortunate, an implication of something broader – a condition placed on these artists that, if they are to enter the hallowed halls of the Academy, they might need to scrub up a bit. And for all that this exhibition is a welcome sign of the art establishment’s willingness to change, it also makes starkly apparent that a lot more is needed to truly redress the imbalances of power that these artworks so eloquently deplore.

Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers: Black Artists from the American South at Royal Academy, London, through 18 June