In an artworld age of uber-slick production values, Robert Nava offers an important, necessary return to the form of the ‘bad’

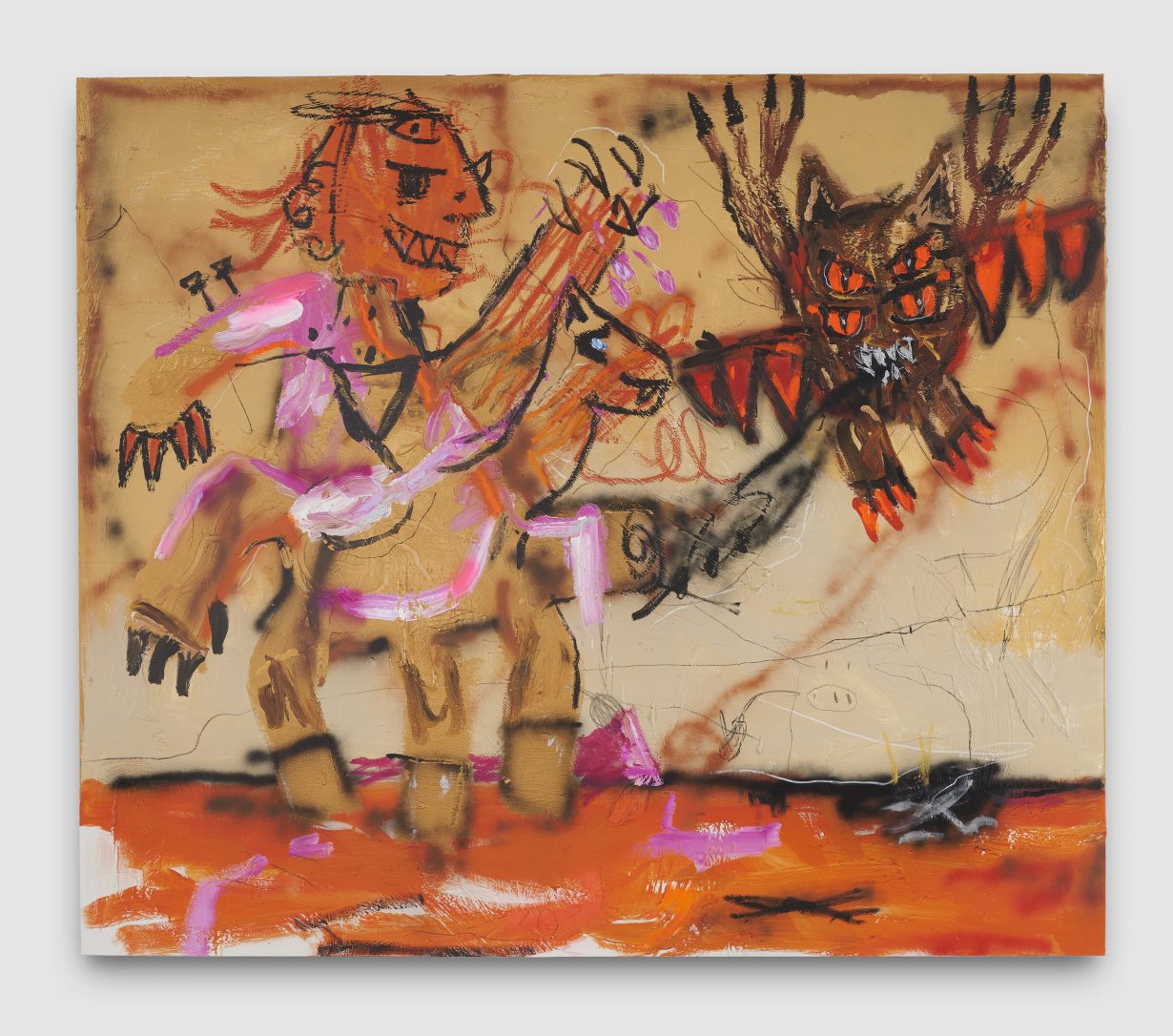

What’s the worst painting of all time? In 1969 it could have been Neil Jenney’s Man and Machine, a wonky image of a figure standing roadside next to his midcentury land yacht. Puke-green abounds, hasty brushstrokes ooze from the unconfident hand. Today, it might also be one of Robert Nava’s paintings. Take, for instance, The Psychology of Ares (2022), an over-the-top brawl – reminiscent of a childhood fantasy – in which a lopsided great white shark, a dragon and a centaur-like creature enact a battle royale as a diminutive (and crappy) castle burns. No gold star here. In an artworld age of uber-slick production values, and when everyone’s self-images are filtered and photoshopped, Nava offers an important, necessary return to the form of the ‘bad’. The painter’s slapdash scenes of angels and demons and dragons exist ‘somewhere between watching Unsolved Mysteries and Ancient Aliens’, mused Nava, in a recent interview with artist Huma Bhabha.

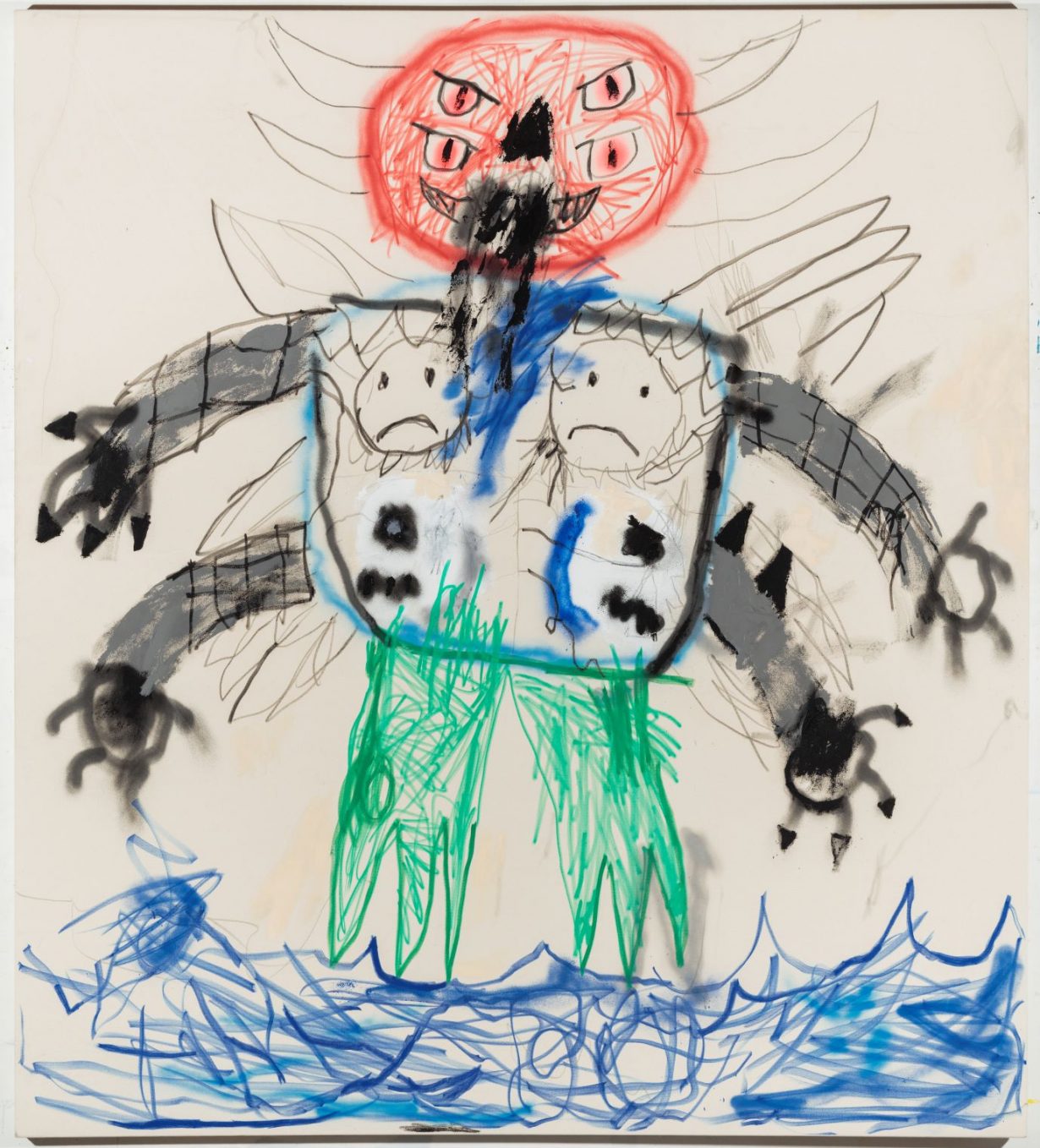

The year is 1997; I am eight years old and playing PlayStation in my friend’s basement. The quest at hand is the just-released Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, a side-scrolling fantasy-horror game that follows protagonist Alucard, Dracula’s half-human son, in pursuit of Oedipal revenge. Nava also jumped, chain-whipped and slashed his way through these demon armies, and he became absorbed with Castlevania’s perfection of two-dimensional graphics that turned away from the promising dawn of 3D; likewise, Nava’s paintings and their sketchy, casual aesthetics are an antidote to the recent shiny hype of the metaverse and NFTs. The side-scrolling language of fantasy and horror manifests in recurrent characters like Nava’s Half Angel, Half Alien 3 (2022). In this third iteration, through a visceral mass of acrylic and oil stick, viewers can make out a figure with angel wings, painted with a series of golden, tooth-shaped forms. Floating against a cloudy blue sky, and over a strip of green, the figure’s torso dissolves into passages of white, pink and cadmium abstraction. A spherical eye – almost as if spritzed with a stencil – anthropomorphises this fleshy glob of paint. Nava adorns the canvas with a few errant scribbles, footnoting Cy Twombly. Like many of Nava’s creatures, this angelic extraterrestrial is a chimera, a hybrid spliced from the artist’s mind and the endless wellspring of popular culture.

“What would 400 years of bad painting look like?” wondered Nava, when we spoke recently on the phone. It’s almost 50 years since Marcia Tucker popularised the term in her 1978 essay ‘“Bad” Painting’, written for her New Museum-curated exhibition of the same title. Then, Tucker defined ‘bad’ painting (quotes included) as ‘figurative work that defies, either deliberately or by virtue of disinterest, the classic canons of good taste’. The best of ‘bad’ painting turns away from ‘draftsmanship, acceptable source material, rendering, or illusionistic representation’ in order to avoid altogether ‘the conventions of high art, either in terms of traditional art history or very recent taste or fashion’. Her essay presented an ironic lens for a new criteria of the ‘good’, and the exhibition helped crown artists like Jenney, Joan Brown, William Copley and William Wegman. Idiosyncrasy and figurative distortion were praised as a means of advancing an ‘anti-rational’ and ‘anti-intellectual’ attitude towards art, as it emerged from spectres of 1960s formalism, Minimalism’s austerity and conceptual art’s brainy rigour. Jenney’s Man and Machine featured prominently in the exhibition. ‘Even if I produced the worst paintings possible,’ Jenney wrote in the exhibition’s catalogue, ‘they would not be good enough’.

Meg with Algae, 2022, acrylic, grease pencil and oil stick on canvas, 183 × 213 cm. Photo: Jonathan Nesteruk © the artist. Courtesy Pace Gallery, London

The son of a steelworker, Nava grew up in the East Chicago of the 90s and 00s, and, ironically, found his process of deskilling, eventually, through a desire to paint three-dimensional perspective. Through deskilling, Nava eliminates any attachment to, or lionising of, technical skill. He renders three-dimensional objects with a distorted sense of flatness and messy linework, leading to canvases filled with a cornucopia of errors and amateur brushstrokes. A seventh-grade field trip to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he saw works by Goya, Ingres and Delacroix, kindled his love of painting. Before his MFA at Yale, Nava attended art school at Indiana University Northwest, a public university in Gary, and there he experimented with painting styles proffered by his teachers. Also well before Yale, he entered what he calls a “deconstructive mode”, and turned away from the pursuit of technically sound representation. In some of the works from his MFA years, we see a clunky, quirky and macabre sensibility that recalls Jenney’s first ‘bad’ paintings, like Man and Machine. In one example, an alligator severs the foot of an unlucky victim, as a fount of ketchup sprays against a blank background. Here, Nava’s hand is minimal and aloof, and the painting’s four forms (the reptile, the casualty’s bottom half, the dismembered foot, the cartoon gore) boast few defining features, outlines or shading. It points towards Nava’s penchant for absurdity, satirical violence and humour, but lacks the recent work’s turn-it-up-to-11 maximalism.

Nava’s work participates and advances the history and traditions of bad painting, and might be called, in his words, “superbad”. His paintings incite the encouragement of fellow artists, but the ire of Instagram trolls and uptight collectors. After Pace Gallery announced its representation of Nava in November 2020 (he had hustled for years in New York as a truck driver, among other odd jobs), consternation emerged as to why the gallery that advocates Mark Rothko’s estate and James Turrell would represent such a premier dilettante of contemporary petit-bourgeois aesthetics – the videogames and movies and other mass media that keep us opiated. ‘People are just furious, just furious’, Pace president Marc Glimcher remarked during a 2021 conversation reported by writer Nate Freeman. ‘What is this shit?’ Sébastien Janssen, of Brussels gallery Sorry We’re Closed, recalled in the same article, hearing from perplexed gallery-goers when he first showed Nava in 2018. These reactions aside, some artists in New York venerate Nava’s approach to showing just how constructed images of popular culture are. ‘He paints figures almost the way Cy Twombly would have had he painted figures,’ noted Katherine Bradford, the materfamilias of many New York painters, in a 2019 interview. Nava, in turn, feels there’s a kinship with Bradford’s work, and that “our paintings [could hang] on an oversized refrigerator” together, a reference to their shared embrace of unfiltered, naive aesthetics.

Over the past decade, painting, at least in New York, has cycled through periods of doubt and scepticism about its use value and relevance, a side effect of the overheated art market and turbulent social and political conditions that demand art’s response. What unites Nava’s paintings with those of Jenney and contemporaries such as Katherine Bernhardt are questions of taste and style, and perhaps more importantly, an embrace of low-budget aesthetics. Nava’s works are the visual equivalent to chicken scratch, and his style mirrors the subject matter, doubling down on the low life, from side-scrolling videogames to B-movie horror, all of which offer an escape from suburbia. Nava’s paintings, however advertently, advance an ethical imperative that turns away from overproduced spectacle while simultaneously embracing its subject matter. To make ‘bad’ paintings now, when New York is more expensive than ever, is to refuse the contemporary art world’s capital-infused obsession with production value and polish, and the charlatanic wizardry of LED lights and an algorithm. “There’s more room in the realm of incorrectness,” Nava says to me. The incorrect, the vulgar, the bad, still today, provide an artistic path absent a door-policy, just as they did in 1978, when Copley wrote to Tucker: ‘There is only bad art’.