The same, but a bit worse? The confluence of new culture wars and institutional precarity is creating a new class of ‘activist patron’

In a letter to the French public radio station France Inter, published in early May, novelist Michel Houellebecq – author of such bleakly misanthropic bestsellers as Atomised (1998) and Submission (2015) – scoffed at those who excitedly declare that, after the coronavirus epidemic and the lockdown, ‘nothing will be the same again’. On the contrary, Houllebecq grumbled, ‘after the lockdown, we won’t be waking up to a new world; it will be the same world, just a bit worse’. Houellebecq noted that rather than ‘change everything’, the coronavirus’s main effect would be to ‘accelerate certain mutations already occurring’ – the rise of online purchasing, contactless payment, teleworking, social media and online content – the main consequence of which would be the continued reduction of ‘physical and human contact’.

With the UK soon joining the ranks of countries exiting their lockdowns, it would be easy to dismiss Houellebecq’s miserabilism. With the easing of restrictions, shops and art galleries are reopening, and museums will soon join them, along with bars, pubs and restaurants – albeit often with complicated and intrusive regulations. And anyway, the last few weeks have seen the resurgence of human contact because many simply started flouting the lockdown rules: at first to go to the park or beach, and then subsequently in the wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations, where thousands of protesters largely ignored regulations on public gathering, having decided for themselves that one of society’s biggest political issues mattered more than merely staying at home avoiding the virus.

This is however, no return to the ‘old normal’ and Houellebecq’s wider observation – that the coronavirus crisis has accelerated already existing trends, is worth pursuing. For the artworld, the hope that things will go ‘back to normal’ is misplaced; in the artworld, as elsewhere, already existing trends have indeed accelerated. The global art market, under pressure from the suspension of the international art fair system, looks set to do badly this year; as art fairs struggle, in vain, to reinvent themselves online, those galleries most dependent on art-fair sales will find it hard to get through to 2021. But, as the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report noted in February, the global art market was already turning the corner on its decade of growth. Largely lost in the noise of the COVID-19 panic, the report pointed out that in 2019, the global art market contracted by 5% on the previous year. While this is comparable to other recent dips, what was notable was that while total sales by value fell, the number of sales grew, suggesting that on average artworks were being sold for less.

Meanwhile, as commercial galleries have tried to adjust to the malfunctioning art market, many public institutions have found themselves in an increasingly fraught debate over their culture, resources and mission in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests. In the US and UK, the protests have inspired fresh campaigns against the institutional and employment cultures of museums and publicly funded galleries, as accusations of institutional and systemic racism have been levelled at institutions such as New York’s Guggenheim, San Francisco’s SFMoMA and New Orleans Museum of Art, among others. This, too, is the acceleration of already present and widespread criticism of the culture of art and its institutions, and campaigns to decolonise everything from museum collections to university curricula. With Black Lives Matter, the decolonisation debate has been conclusively brought into the streets: while for several years, arguments have raged over the statues of slavers and colonialists, protestors have acted, summarily pulling down offending monuments.

With a declining art market, constrained global mobility and art institutions in a state of unprecedented cultural crisis, what might the ‘new normal’ look like? While the biggest institutions in international cities like London try to work out how they can reopen without haemorrhaging cash, the crisis in institutional culture will likely see institutions move even further – when they eventually reopen – to be seen to respond to criticisms of their failings over cultural diversity, gender and ethnic representation, while issues of patronage and corporate responsibility will become increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to negotiate. For example, to mark Pride month, the British Museum has just announced that it is adding five artefacts with an LGBT+ cultural history to its permanent displays. But when the museum attempted to align itself to Black Lives Matter by issuing a statement of solidarity, this merely fuelled renewed calls for the restitution of its artefacts to Africa and elsewhere.

Less concerned with reopening, institutions are more concerned about what kind of institutions to reopen as: so while London’s big national museums worried in a joint statement last week about how and when they could open their doors again ‘in a financially sustainable manner’ (implying that they couldn’t reopen if the foreign tourists didn’t return), the joint statement of museum directors then mused that ‘our collections are … to be discussed, challenged, and loved: a role of particular significance as we reflect on current debates around crucial issues including racial equality, social justice, and climate change.’

The ‘culture wars’ over representation, then, and the tendency to relate institutional programming to the politics of identity and to broader political issues, seems likely to accelerate, not abate. That this should happen into a period in which institutions will be under intense financial pressure means that many institutions will turn to private patronage for support, which in turn will encourage patrons to take a more explicitly activist role in supporting activist programming.

Private patrons with agendas, not just cash, will become more significant, further concentrating power at the top, and in private hands: Maja Hoffman’s LUMA foundation ‘focuses on the direct relationships between art, culture, human rights [and] environmental topics’; Francesca Von Habsburg’s TBA21 addresses ‘the complexities and urgencies of the age of the Anthropocene’; in May private patron group Outset Contemporary Art Fund announced £150,000 funding for Edinburgh’s shuttered Inverleith House art gallery (funded until 2016 by Arts Council Scotland), to reopen as a ‘Climate House’, a space that ‘seeks to change the way we view the climate emergency and biodiversity crisis’. Property billionaire (and Serpentine Galleries council-member) Nicolas Berggruen’s thinktank the Berggruen Institute funds its ‘Transformations of the Human’ artist-fellows, who are ‘commissioned to create projects that explore the rapidly shifting boundaries among our notions of nature, technology, and humanity’. Berggruen fellow Anicka Yi will undertake the 2020 Hyundai Tate Turbine Hall commission this autumn.

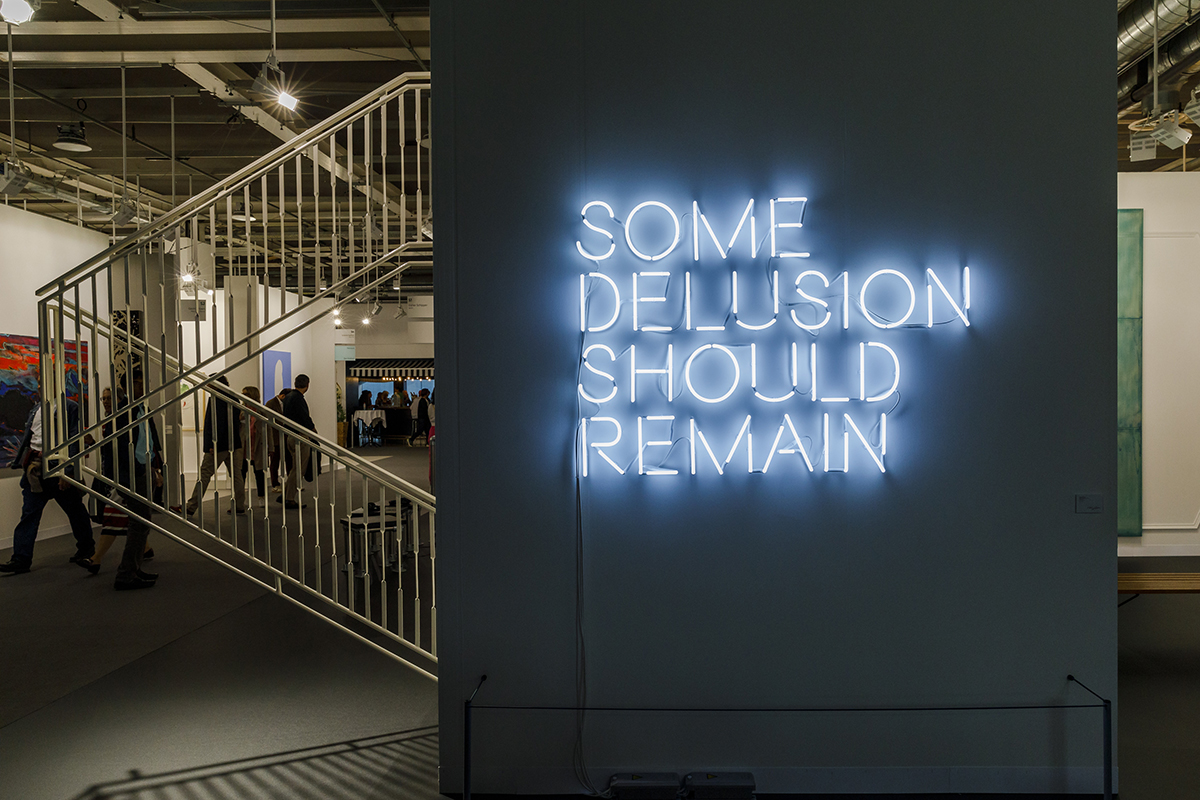

Is this better, or ‘a bit worse’? Artists will, of course, respond to the new interests of activist patrons. Many artists will already agree with them. But while the politics of racism or the future of the environment affect everyone, and demand that everyone takes a stance, the existing trajectory of the artworld points to a future of contradiction.

Institutions will attempt to retrieve some sort of cultural credibility, but their rarefied and exclusive status will persist, reinforced by their potentially increased dependence on wealthy patrons (albeit those who will now have the ‘correct’ ethical credentials). Will their programmes – and by extension the artists they support – become even more narrowly focused on confirming the shifting cultural and political priorities of their backers? As more activist patrons and institutions seek political credibility by cleaving to particular social issues and constituencies, will this foster differences of opinion among artists, or encourage a cultural artistic pluralism, or the genuine devolution of power to smaller organisations and groups of artists? In many ways it seems not. There’s a real danger, then, that it might even be a bit worse.