James Turrell’s euphoric voids, Paul Klee’s messages to the future and Charles Ray’s aluminium tractor – commercial galleries are back in business

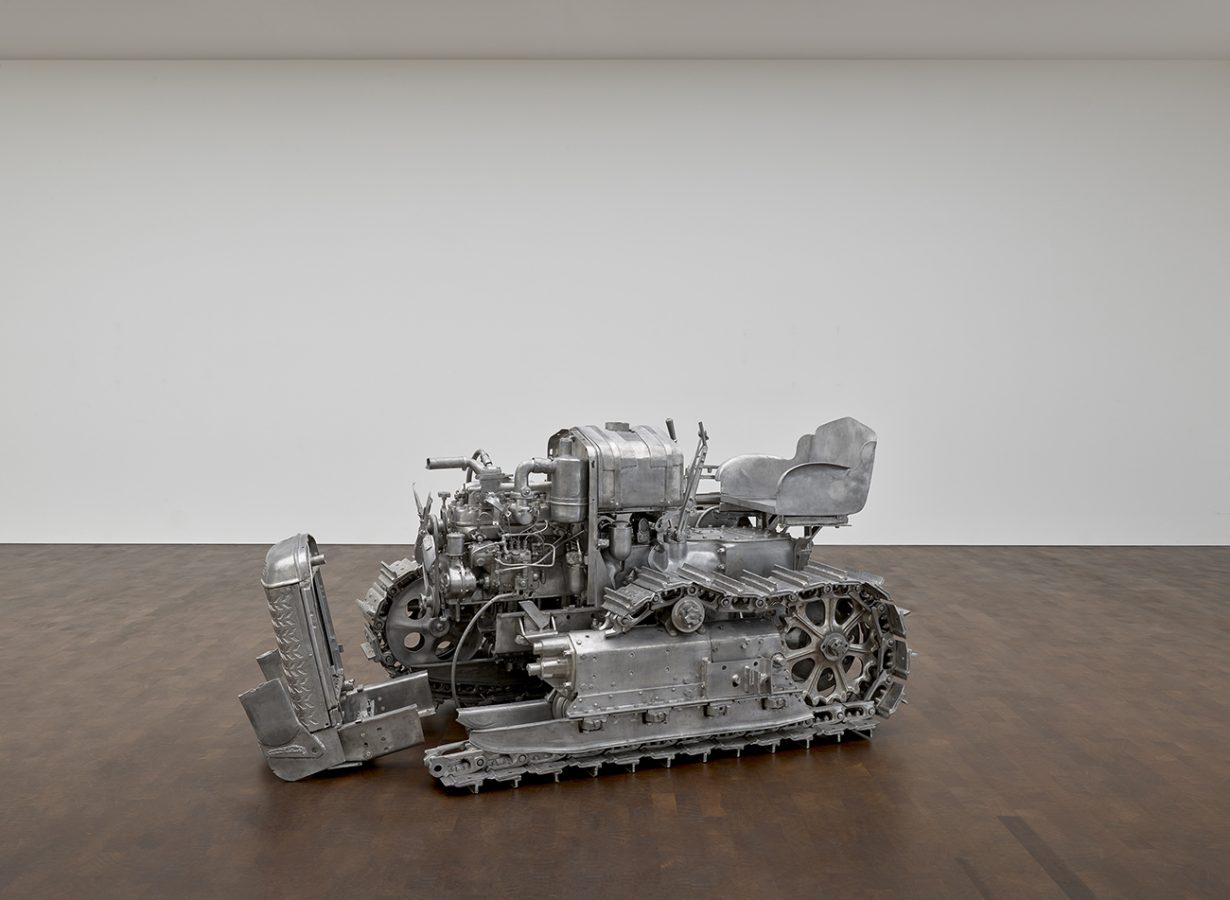

Three months working from home, for the most part not looking at physical, material artworks – actual things – must mess with your head a bit. Something to do with visual perception. Standing in Gagosian’s spacious, cool, evenly lit Grosvenor Hill gallery, I’m looking at Tractor (2003-04), an all-aluminium life-size remake of an old agricultural tractor, by Charles Ray. It’s the first time I’ve stepped inside a gallery since lockdown, and while looking at the tractor’s intricately rendered valves, carburettors and other internal mechanics, I’m hit by a sudden, lurching sense of visual parallax – as if I’m seeing each little part from two different positions.

Urs Fischer, and Charles Ray’, installation view, 2020. Courtesy: Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill; photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates

Which, of course, I am, since that’s how eyesight works. This sensation lasts for a fraction of a moment. Long enough, however, to realise that for most of this year I’ve been staring at a flat screen, and objects – a bottle of milk, a cup of coffee, or whatever – don’t usually get my concentrated visual attention. I’m out of practice, in other words.

Such are the peculiarly refreshed sensations of visiting art galleries after lockdown. Seizing on the lifting of restrictions, many of London’s more high-end galleries have made an effort to reopen this week, with facemasks mostly obligatory, ubiquitous hand sanitiser and a variety of more or less successful online appointment systems for guests. On this sunny Tuesday, I mostly have the galleries to myself; another odd experience and part of the general quiet which still dominates the usually busy and noisy West End.

Urs Fischer, and Charles Ray’, installation view, 2020. Courtesy: Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill; photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates

The strangest sensation, by far, is the sense of uplift at actually seeing things for real again. You don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone, someone sang once, and while you had free access to the normally functioning art gallery system, you could spend a lot of time griping about the ancillary troubles of the artworld – the mega-galleries and the art market, collectors and art fairs.

Not that that stuff much bothered me before. These things may be the system as it stands, but in the end, we make judgements about artworks. Ray’s Tractor, for example, is shrewd and generous in its play on function and functionlessness, work and luxury; whereas in the same show, the huge, bombastic Urs Fischer sculptures – deranged scalings-up of amorphous lumps of clay, cast in aluminium – loom over you, and their disenchanted desire to exploit a resigned assumption of systemic artworld excess dates them badly, makes them quickly tedious. Same gallery, same show, but look – one work is better, one is worse.

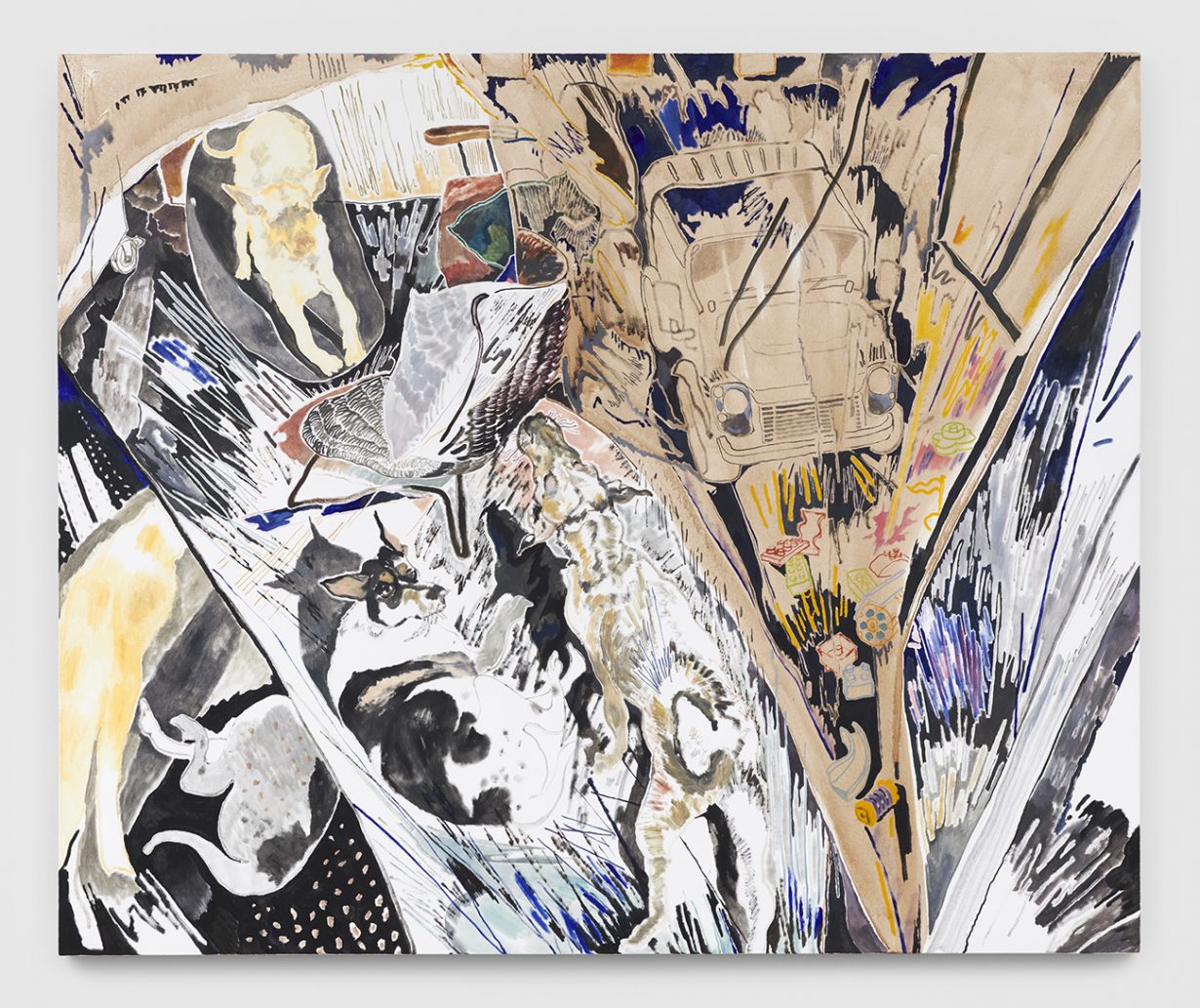

Life, in other words, is now too short to put up with not-so-good art just because it happens to be there. Happily, there are good things in all these gallery shows. At Simon Lee Gallery paintings and drawings by Hong Kong-based Chris Huen Sin Kan focus on the everyday of the artist’s life – his partner, his child, his dogs and the surrounds of his home and studio. Intimate though these scenes are, they take shape in a dense all-over buzz of drawn line and washed oil, and his family appear almost like mythical figures, as if the artist were celebrating the importance of the ordinary, of human feeling and care, but without a speck of indulgence or easy sentiment.

Some shows were cut short by the lockdown in March. Across Piccadilly, at Thomas Dane’s two spaces are works by Los Angelino Ella Kruglyanskaya; paintings of women, painted by a woman, about the politics of painting paintings of women, Kruglyanskaya’s bold, colourful caricatures depict women as they might appear in fashion tropes from the 1980s and before. These are glamourous stereotypes from bygone ages of femininity, with constant hints to modernist abstraction and masculine art history (colour fields, Mondrian-like colour primaries) subverted – as it was – by the supposedly ‘feminine’ culture of fashion design. A frequent protagonist in Kruglyanskaya’s paintings is the paintbrush itself, a not altogether benign presence, often imposing itself or encroaching on the forms of the figures shaped by Kruglyanskaya’s own brush.

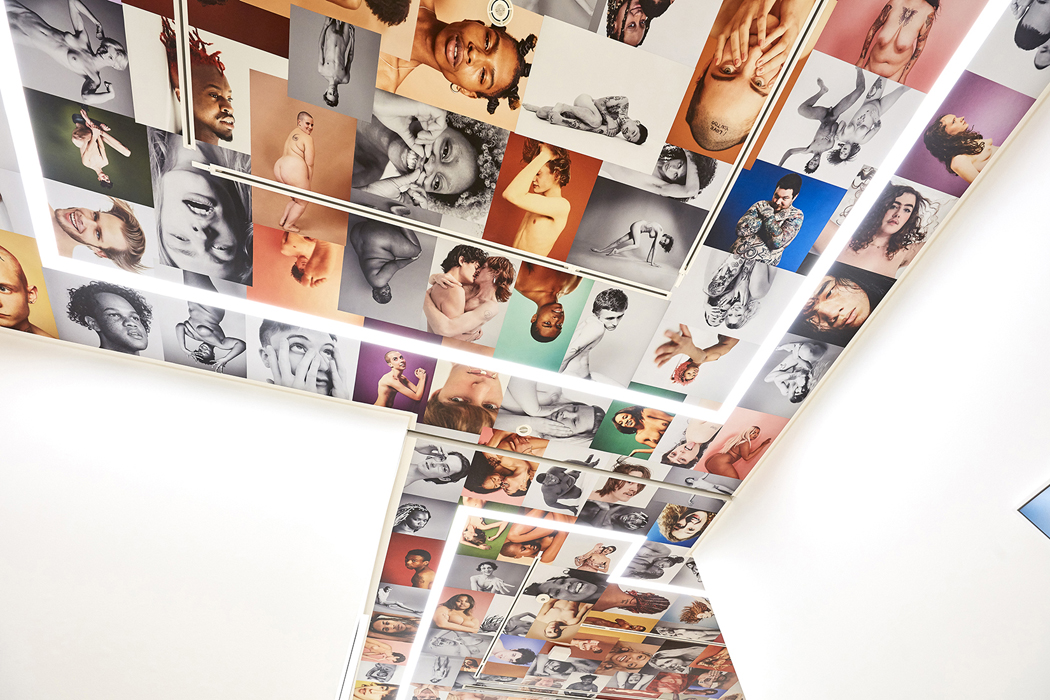

Maybe it’s because of the imposed constraints of the lockdown, on human life and desire, that Ryan McGinley’s expansive show of recent photography at Marlborough seems elegiac. McGinley is famous for his deeply idealising portrayals of the lives of young, ordinary urbanites, often naked, in edenic exurban scenes. Here McGinley’s subjects dance naked in the fields, kiss among the trees, while above, covering the whole of the gallery’s ceiling, is a mosaic of studio portraits of countless, happy, beautiful, naked men, women and children. McGinley’s unrelenting focus on style-magazines’ fantasy of self-realising, liberated individuals, though, feels outrun by events. You hope all these people are well, or at least coping with the world as it is right now.

Can one blame artworks for not being able to cope with the world as it is now? At Thaddaeus Ropac, Hito Steyerl’s three-screen video The Tower (2015) rehearses a strange narrative about a CGI modelling company in Russia, which makes renderings for speculative developers as well as emergency evacuation and warzone simulations, against a backstory of Saddam Hussein having wanted to build a new Tower of Babel. Left over from the earlier show of Steyerl and Harun Farocki’s work at the gallery, The Tower reflects on virtuality and the age of permanent war – the peculiar horror of simulating the catastrophes happening for real to others, elsewhere. Right now, though, the emergency has come crashing in on us here – a turn of events which, you could argue, The Tower bleakly anticipates. Farsighted as Steyerl’s video may be, it reveals that critique is of little comfort for those making politicised art – or indeed those looking at it – when the conditions for viewing it are themselves in trouble.

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

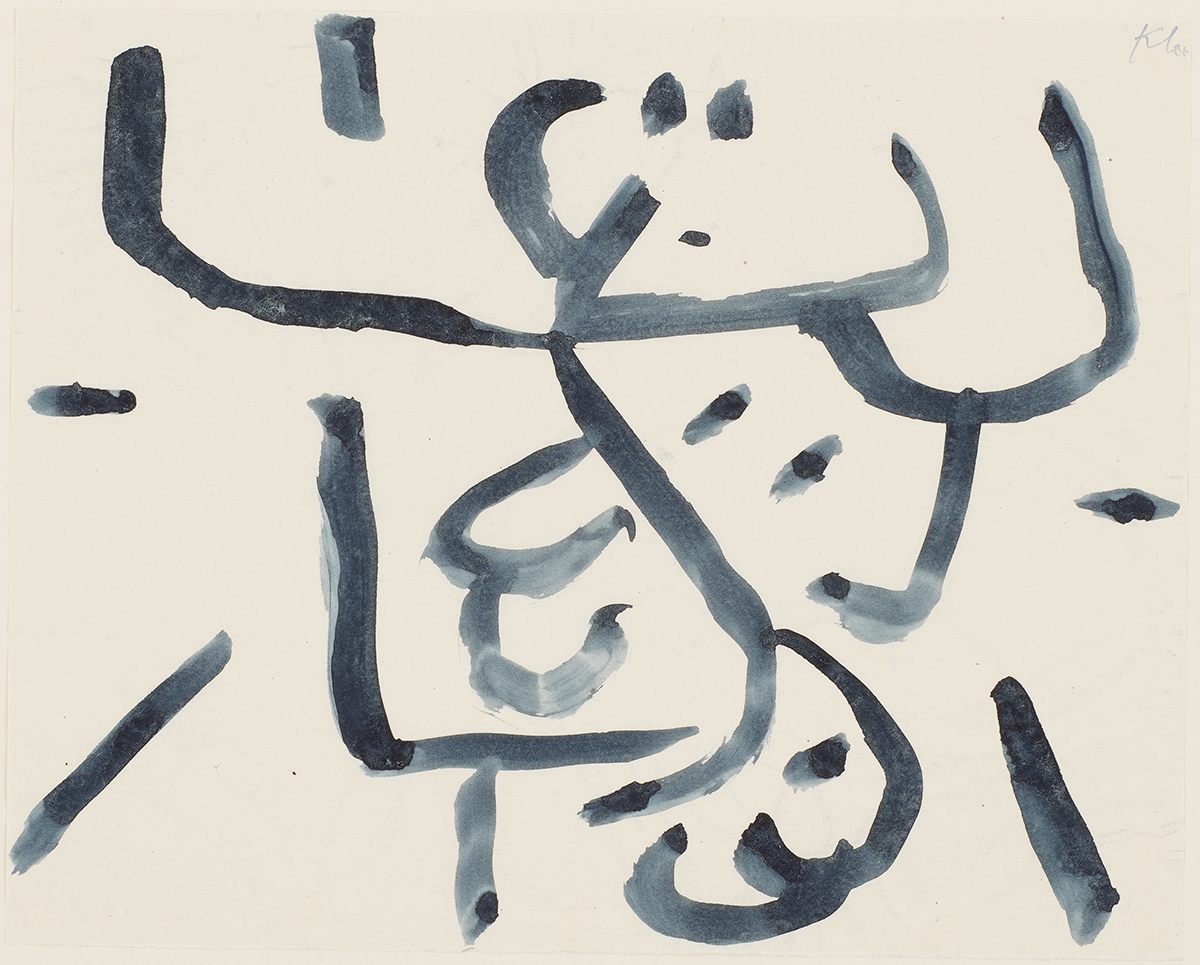

In that sense, artworks are often refuges where good things still go on while outside… well, things are maybe not so good. So, one can spend time with James Turrell’s euphoric colour-changing voids, still on at Pace. Two ovoids and one circular aperture, built into the gloom of Pace’s cavernous space, cycle through different tones with imperceptible, time-dilating slowness. Colour, visual experience, bodily experience and time are also at stake in Bridget Riley’s exquisite, ever-shifting preparatory drawings and paintings on paper at David Zwirner. Riley shares Zwirner’s reopening with works on paper by Paul Klee – often mystically lucid reductions of bodies and landscapes, turned into a kind of calligraphic symbology. It’s a distant, modernist art history, of course, and worth seeing for that – a century on from when they were made, little telegraphic messages from a disappeared past to our future.

In the vitrine of ephemera, among little gallery catalogues for Klee’s first shows in London and suchlike, are photographs of Klee. One is of Klee and his son, Felix, the two standing on Klee’s balcony in Bern in 1934, Switzerland, between them an easel with a painting. Klee had by then emigrated to Switzerland from Nazi Germany, having been suspended from his teaching post in Dusseldorf, his art deemed ‘degenerate’ there. Artworks can’t much influence the world around them, but yet they are worth seeing, and it’s good to remind oneself that galleries are better open than shut.