What Models Make Worlds at Ford Foundation Gallery, New York challenges the bias and myopia inherent in contemporary algorithmic models

The bias-riddled frameworks and myopic visions endemic to algorithmic models today are taken to task in this gimlet-eyed group show, held at the fledgling gallery arm of a philanthropic powerhouse. (The exhibition, previously titled Encoding Futures, travelled from Oxy Arts in Los Angeles, where it was on view in 2021.) With varying degrees of explicitness, the featured artists ask whose interests such algorithms – which are typically guided by the pursuit of capital and design philosophies like ‘Move fast and break things’ and ‘Don’t make me think’ – serve and whom they disenfranchise, harm or erase. The majority of the works on view are social justice-oriented without being didactic to the point where open ends are foreclosed. Instead, critique feeds speculative worldbuilding, wherein artists – and viewers – imagine what techno- logies encoded with feminist, antiracist, decolonial or anticapitalist epistemologies might look like.

Bias exists at the point of data collection. Mimi Ọnụọha’s Library of Missing Datasets, Version 1.0 (2016) addresses meaningful lacunae in a datafied world as it plays with the veneer of neutrality conferred by administrative aesthetics (and terminologies like ‘data collection’). A visualisation of absence, the work comprises an open filing cabinet glutted with empty folders labelled with subjects such as ‘The economic value of the activities of housewives’ or ‘Mosques and Muslim communities surveilled by FBI/CIA’. Mindful data collection, labelling and training are critical to Feminist Data Set (2017 – ongoing), Caroline Sinders’s effort to build voice-responsive AI structured by communal, intersectional feminist values from the ground up. Gallerygoers are invited to sit at a desk beneath vinyl instructions as to what qualifies as feminist in Sinders’s schematic (‘intersectional, queer, indigenous, trans’) and fill in a standardised ‘Feminist Data Set Submission Form’, submitting ‘overlooked or ignored’ feminist data for consideration in the dataset.

Whereas Sinders casts a necessarily wider net, Stephanie Dinkins goes small with Not the Only One (N’TOO), Avatar, VI (2023), a conversant AI system built using oral histories from three generations of Black women in the artist’s family. The project grew out of Dinkins’s experience with the social robot Bina48, which approximated the consciousness and appearance of Bina Aspen Rothblatt, a Black woman, but did not appear to be coded with embodied awareness as such; when asked about racism, for example, Bina48 tended to give conceptual rather than experiential answers and then changed the subject. (A video snippet of Dinkins’s interactions with Bina48, Conversations with Bina48 (Fragment 11), 2014 – ongoing, is also on view.) Dinkins’s AI, appearing as a youthful-looking Black femme with grey hair, hovers onscreen, waiting to answer questions from visitors. When I was at the gallery, the avatar refused to speak or respond to me; a gallery attendant attempted to rouse her, asking, “Do you know your people?” increasingly loudly to no avail. While glitches are to be expected with scrappy AI realised without corporate or governmental resources, there was power – a kind of glitch feminism in action – in the avatar’s refusal to accede to this visitor’s demands on her time and knowledge.

That people are becoming accustomed to issuing brusque commands to feminised AI is taken up, along with questions around domestic surveillance, by Lauren Lee McCarthy’s LAUREN (2017 – ongoing). After delivering networked devices to participants’ homes, McCarthy became a ‘human Amazon Alexa’, watching the inhabitants, following their commands and anticipating their needs. The gallery features a home without privacy: a minimalist open cube with a window, a pink surveillance camera (aimed inside) and a few domestic trappings. Video screens play surveillance clips as well as spoken, infomercial-style testimonials that evince the emotions experienced by users of McCarthy’s ‘automated’ services: feelings ranging from gratitude (“LAUREN was actually able to help her manage her medication”) to trepidation (“I like the idea of [LAUREN] being in support but not in control”). Cultural imaginaries around AI are of course not only gendered but also racialised, a thread that Astria Suparak pulls with Sympathetic White Robots (White Robot Tears version) (2021/2023). The vinyl print collage features scenes of emotionally distraught AI – all of whom are white-coded – from popular sci-fi flicks like Blade Runner (1982) and Ghost in the Shell (2017). This wry yet weighty piece is part of Suparak’s research project Asian futures, without Asians (2020 – ongoing), which lays bare American sci-fi’s disturbing fixation with superficially Orientalist futures populated by white protagonists. Within that white supremacist cinemascape, these robots’ proximity to whiteness can be seen as making them sympathetic subjects: a shameful testament to the extent to which technological futures must be reimagined, particularly in the West.

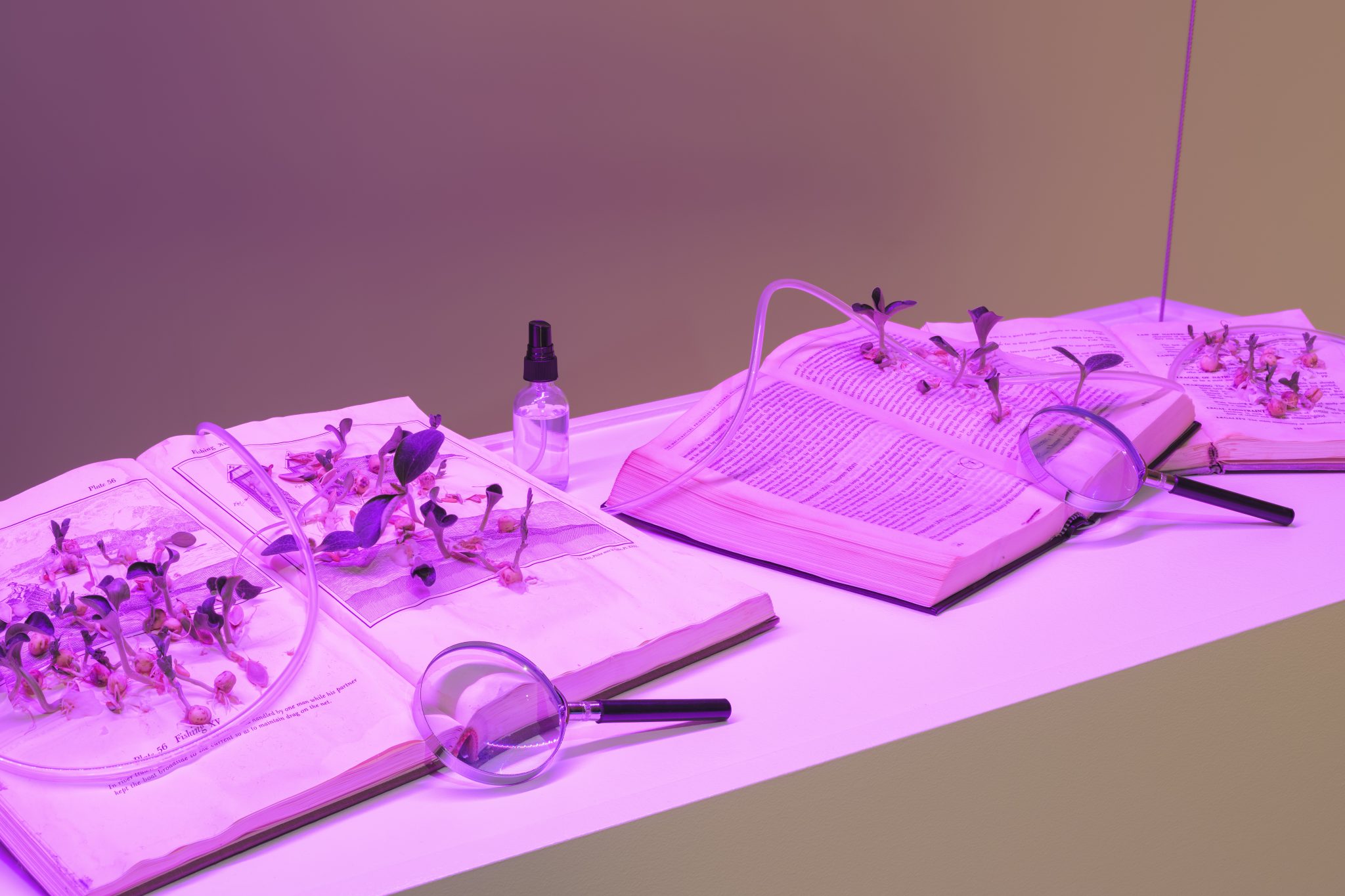

Such reimaginings can take a multitude of forms, only some of which are anthropomorphic avatars. To make Botanic Attunement (2023), Aroussiak Gabrielian splayed open Western science tomes – symbols of vaunted ‘empirical’ knowledge systems – which she proceeded to seed and place under pink grow lights. With the help of gallerygoing humans, who can spritz the setup with nutrient feed, legume and gourd plants have grown through the pages; by the time you read this, a verdant mass has likely fully occluded the line ‘Not everyone can become a programmer’. The installation becomes a lively tableau in which plant intelligence and sociality overtake limiting human knowledge paradigms. As it expands the exhibition’s premise and enlarges the definition of ‘technology,’ Gabrielian’s piece underscores that that the intelligences to which we should closely attend are not only human, or artificial.

What Models Make Worlds: Critical Imaginaries of AI at Ford Foundation Gallery, New York, through 9 December