From 2015: The two friends catch up on the occasion of their having almost simultaneous solo institutional exhibitions in Seoul

Part One: Haegue Yang discusses her current solo exhibition at the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul

Heman Chong Your exhibition has a curious title…

Haegue Yang Shooting the Elephant 象 Thinking the Elephant contains a Chinese character, 象, which is a hieroglyph in itself. I found it fascinating to imagine the origin of this character, since the elephant doesn’t inhabit any region in which Chinese was or is used. The same goes for another metaphor of the exhibition, which is a Lion Dance, a folk dance that’s widespread across the whole of Asia, a region that’s not inhabited by lions. You won’t find an elephant or a lion in the show either. They served as a metaphor of living – a living that was only imagined, yet which was territorialised as a part of folk culture so that it could be even claimed as ‘ours’ and understood as something ‘familiar’.

Another reference in the title comes from literature, George Orwell’s short story ‘Shooting an Elephant’ [1936, about a British police officer in Burma who feels forced to shoot an elephant] and Romain Gary’s novel The Roots of Heaven [1956, about an environmentalist in French Equatorial Africa who sets out to preserve elephants from extinction]. In the first, the elephant appears as an unpredictable, yet innocent animal (or cipher for nature), killed by the irrelevant human-centric power system of colonialism. Orwell (who is recounting his experience as a police officer in colonial Burma) was pressured by that system and eventually had to shoot the elephant when he was surrounded by thousands of Burmese expecting to witness the violence of their coloniser. In the other work, the elephant shows its power as well as weakness: on the one hand it provides a most unlikely source of hope to Morel (the main protagonist of Gary’s novel), who subsequently wishes to preserve the African elephant from extinction; on the other hand, the elephant is nothing but a helpless and vulnerable species, which can’t be saved despite Morel’s complete devotion and eventual sacrifice.

Besides that, there are two general aspects of the show that are worth mentioning at the beginning: one is the lighting, the other is the wall treatment. The lights on the ceiling of the Ground Gallery at Leeum are all pointed in one direction, not so as to illuminate the work, but so as to act autonomously. This is done to liberate the lights from their functional existence in this completely open space.

Three right-angle-triangle-shaped built-in walls, hung upside down from the ceiling, have been treated so that each side is distinctly different from the other: the outer surface has an ordinary finish while the inner side is rough and grainy like sandpaper. Also I’ve allowed the grid of the panels on this inner side to be revealed. Over the course of the exhibition, there will be some stains from people touching this side of the walls: this contact and the sensation of texture, as well as the collective trace of visitors, will be significant.

HC Let’s talk about Storage Piece [2004]. It is a work that has been discussed greatly within the context of your practice. Why did you choose to exhibit it now, among the other works in the show?

HY Storage Piece is located in the middle of the exhibition, it’s a work originally made for a show while I was on a Delfina Foundation residency in London. It is often said that Storage Piece marks an important turning point in my practice. The background to it was that there was an offer of a commercial gallery space for an exhibition but I had no ability to make the show, either financially or physically. And parallel to this offer, there were numerous requests that I should pick up works, returning from other exhibitions for which I couldn’t afford any storage space. So I proposed to use the exhibition budget to bring all those works – which remained packed on palettes – together in an exhibition. There were about 13 pieces in all, some are complete, some of the works only survived in parts. There are also early pieces included in Storage Piece, for instance from 1994, which had never been exhibited, but which I was asked to remove from my flat in Frankfurt, where I was no longer living.

This type of personal circumstance hadn’t been a part of my practice at that time; indeed it had seemed inevitable not to assert this kind of circumstance, but it came to a point, through Storage Piece, where I did, and this helped me to break this conceptual boundary. Within the tendency to cling to both the physicality and the fetish of conceptualism inherent in Storage Piece, there is a kind of concern and doubt that remains and that is contained within it. Personally, I’m very pleased to have Storage Piece on view here, a work that a lot of people have heard about many times, yet not so many people have encountered; it is important that people face the work in person.

Storage Piece is always accompanied by a speech that will be given at the opening of the exhibition by someone other than myself. The script for this speech has been modified slightly each time it has been delivered, reflecting the changed circumstances and the ways in which my own reaction to the work cumulatively changes over time. The crisis born out of a simple, poor circumstance disappears, while new challenges around the piece emerge, so the modification is necessary. The speech describes a couple of pieces found within the work that people cannot see, because everything is wrapped up. Very much

a monologue, which fluctuates from being super-confident on the one hand – suggesting that this is a great solution, even a brilliant one, given the challenge of the circumstances – but at the same time being filled with doubt, based on a belief in concept and idea – that one should not hold on to the physicality of the work. Overall, this oscillation itself reinforces the potential and the ecology behind the work. It reflects a kind of timid negation of the ‘either/or’ dichotomy

of an object. When Storage Piece was sold, I handed over the conceptual authority over the work, thus the collector could unfold the piece according to his own desires and situation.

HC So he could have unpacked the work?

HY Indeed. In 2007 the collector Axel Haubrok proposed that he unpack the work in order to see what he had collected. As part of this agreement, under the title ‘Unpacking the Storage Piece’, everything would be fiercely unpacked and neatly installed. I agreed, and the traces of Storage Piece – the packaging – were also included in the exhibition, as ‘Cabinet of Packaging’. And there was a new speech written for this chapter. So ever since then, Storage Piece has been unpacked many times, sometimes gradually, sometimes as it is.

HC Let’s move along to the next work. Tell me more about your light sculptures.

HY Here there are six individual light sculptures, which are in the collection of Leeum, shown as one installation, Seoul Guts, which was first exhibited at Artsonje Center in 2010 (that exhibition, Voice Over Three, was also my first institutional exhibition in my hometown; this one is my first in five years). I spent three months in Seoul preparing the show, and Seoul Guts is one of very few light sculptures that I produced out of my studio. The portrait of the city of Seoul is articulated by the small objects, mostly expressing ridiculous and trivial desires and the nostalgia of people. Here you see an object made of seashells and urban waste, disguised as a romantic souvenir of a possible holiday, which I collected from seafood restaurants, day by day. There you see some artificial plants, cosmetic supplies, pseudo health devices, all of which constitute a pitiful portrait of Seoul. Pill cases were somehow most touching to me.

HC Why were these the most touching for you?

HY Seoul is full of people who are ‘sick’: in a sense they’re all not fit, they’re tired and wasted. The daily life in Seoul is just tough, you come up with ideas to survive – taking vitamins or medicine against cancer, for diabetes, it’s just crazy. They’re all functioning, but at the same time they’re not functioning at all. There is no border any more between healthy and sick. These two things build a parallel, and in this you still have to keep going. For example, these objects I use, these small objects for massaging your body, it’s at once humorous and pitiful. You only can spend a small amount of money with such a big hope that it will make you feel better. These items I discovered while I was shopping, or ‘hunting’ for material; I think this shopping process in the city was crucial.

HC What was the trigger for you to use these standing structures to hang these objects on?

HY At the very beginning I started using IV (intravenous) drip poles, which are frail, much like a line in space, on which you cannot hang so much. I used them for the first time in 2006, in a project called Sadong 30, at an abandoned house. The ceiling in that house was about to collapse, so you couldn’t hang anything from it. In order to illuminate the space, I registered and reinstalled the electricity supply, but I needed a stand from which to hang lights. The IV poles were easy to get and it seemed natural to have them in that space. But I wasn’t aware of the association of that object with body and health. After using them once as a lighting device, I started to make sculptures of out this stand. I was very touched by the melancholic look of it, how the cables are draped from/over it. Over time, it became an autonomous sculpture. By the time I switched over to the much chunkier clothing racks, each stand became anthropomorphic, to portray certain qualities of possible figures.

HC In a way you’re building characters.

HY Yes, quite. In this series it comes across very strongly. Originating from the Sadong 30 project, where I plugged in the lights, it became apparent to me that this work comes from this gesture: plugging into a power source. This gesture meant a lot to me. The house was locked up for many years, and the address, Sadong 30, was dropped out from the redevelopment of the city of Incheon. So there was no electricity, no water, and the house was kind of dead. When I succeeded in reregistering the address in the city council’s system in order to reconnect the electricity, the house could finally be illuminated. I locked the space with a lock that had a number code on it so that people with the code could have 24-hour access. I had limited the luminosity of each bulb to under 25W; again, at the beginning I was afraid that the bulbs would get too hot while there was no guard or other attendant there, so it was a practical decision. But over time I really liked the low luminosity, because it prevented the lights from being absolutely functional: they would be able to light up little corners – efficient enough. The light sculptures inherited this principle, where each bulb is only 15 to 25W.

HC What are these chairs and tables on the other side of the space?

HY In 2001 I was commissioned to conceive the so-called VIP lounge for an art fair, Art Forum Berlin. Commenting on the aspect that one can only access this space with a VIP pass, I decided to equip the space with furniture pieces borrowed from Berliners, whose equivalent significance (VIP) can be only measured by their participation rather than predetermined and hierarchical status. And people (VIPs) could sit on the furniture (from VIPs), achieving an open heterogeneity. The loan of the furniture would be for the duration of the exhibition, and each piece would be returned after the show. I continued to adopt this principle and made a lot of lounges ever since in the middle of exhibitions, and now this is the Seoul version. Seen in the same space as Storage Piece and Seoul Guts, you can sense that they are different configurations of similar observation, an expression of my position as a semi-insider/outsider.

HC Let’s address your new work in this show. Can you walk me through it?

HY This is a new series of sculptures titled The Intermediates. They are made of straw, woven into different architectures and figures. They create a kind of ‘parcours’ through a set of obstacles. These pieces reference actual architectural sites, such as those produced by the Mayan civilisation, the Borobudur Temple, and features found in a contemporary Islamic mosque with minarets in Russia. In between them there are figures. Some of them are abstract, some are more figurative.

HC This material that you use, is this real straw? How did you discover and begin to work with this material?

HY No, it’s artificial straw. By critically reexamining the notion of ‘folk’, I realised that the use of natural straw would only conform

to the given narrow idea of ‘folk art’, confirming the notion of ‘us,’ which is often a race, nation, religious or language group, etc. But this artificial straw gives me a bit of distance from this definition of ‘our tradition’, empowers the works and makes them immune to this tribal claim. The project is not about expressing traditional craftsmanship, but to take a step out of it, to become alien to or a hybrid of it. In a sense, for me, they rather associate with rituals and exotic forms than the familiar.

HC You are personifying the technique, extending the technique as a metaphor, rather than simply mastering the technique of straw weaving. It’s far from rejuvenating the idea of folk.

HY It has never been a primary feature of my production method, but I always worked with two very different ways simultaneously. One relies on using industrially manufactured objects, while the other is based on craft – almost a domestic way of approaching craft – believed to be of low efficiency – such as crochet and knitting. At some point I realised that I’m completely into weaving. But a very inefficient weaving. I used to take a lot of photographs of these straw wraps around trees over the winter in Japan and Korea. These appeared once in a while as reference material in my catalogues, but I never used the observation of straw wrap, realised as a production yet. But when I settled in Seoul a year ago, the first thing I wanted to learn was straw weaving from a craftsman, and The Intermediates was initiated.

Part Two: Heman Chong talks about his current solo exhibition, at Artsonje Center, Seoul

Haegue Yang Are these all new works in the show?

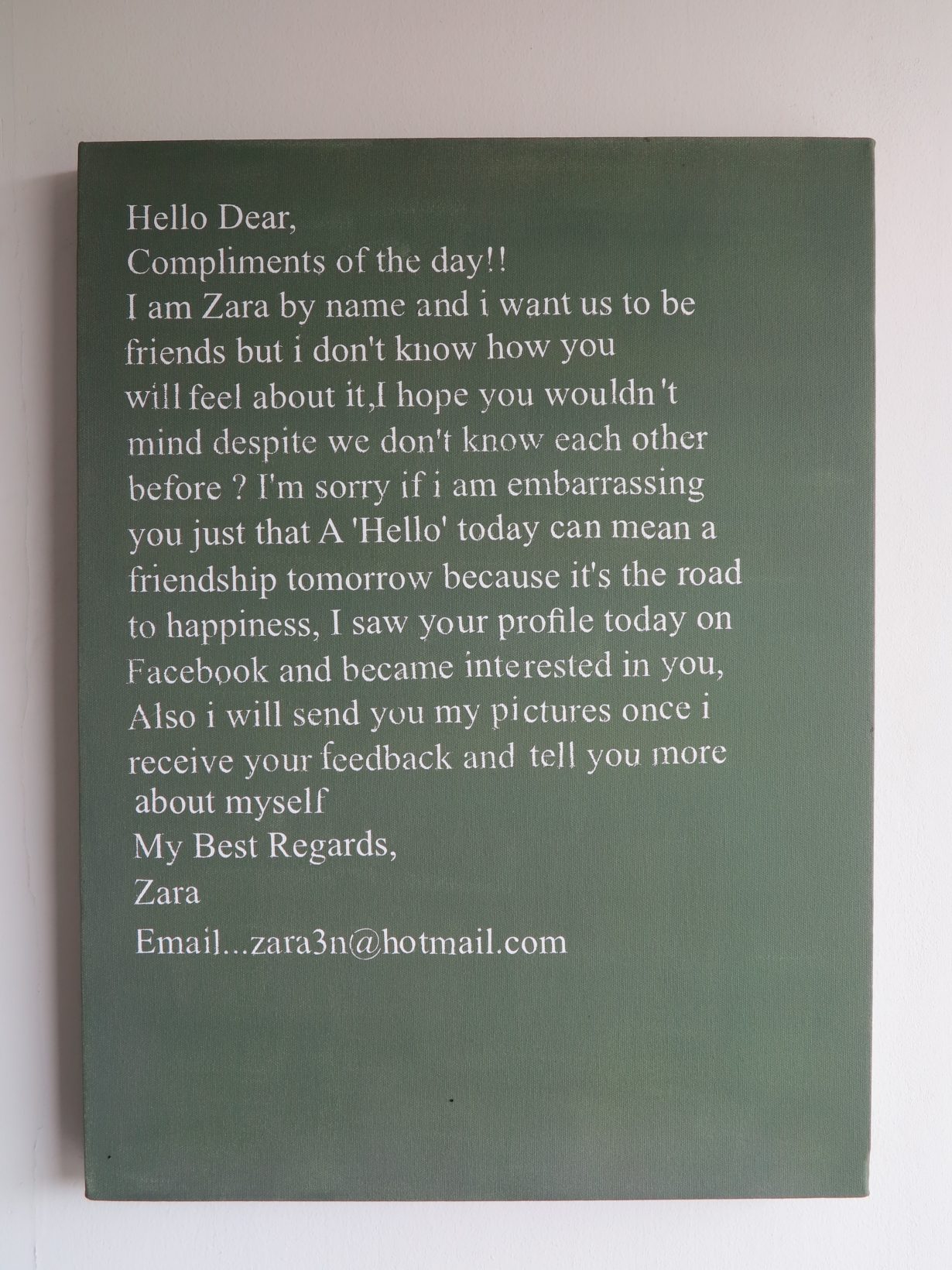

Heman Chong The banner, Welcome! (Hung Wrong), is a new work, as are the poster, Past, Lives (Art Sonje 1995–2014), the extinguishers, Safety Measures, the boiling water, Boiling Point, the email painting, Emails from Strangers (Zara) and the smoking corner, Smoke Gets In (Your Eyes) [all 2015]. The abstract paintings from the series, Things That Remain Unwritten, I consider old pieces, since they’re a part of a series I started in 2014. And this video is an intervention that was originally produced in 2008.

HY Why do you call it an intervention?

HC The work is called Until the End of the World (Paused) [2008] and it really relies on a very direct intervention of the first member of the audience that comes into the space: the film is played until the person comes in view of it and is then paused. The paused image is the object that will be shown throughout that day.

HY You can also say that it is a performance.

HC I think the terms are very problematic. Terms usually don’t stick around very long for me. In fact, given a choice, I would like to define every single work I make as an object. The word ‘object’ is very beautiful because it is a generic term that can encapsulate everything.

HY And do you consider this show a typical show of yours? Or is there a difficulty in defining what ‘typical’ is anyway?

HC I think the layout for this show is very close to me. It is a way of suggesting a reason why people should still want to visit exhibitions. For me, I do it because it means something to me to go out of my studio and to encounter another space, so it’s not a process of judging but of experiencing. It’s very different from accessing a work via a photograph, or other documentation.

HY So you make a distinction between the works and the exhibition?

HC The works in the show are autonomous and they are part of this constellation of things. When I started thinking about this exhibition, I was touched by something written by Raymond Carver. He said that the reason why he wrote short stories was because of two things: he was firstly an alcoholic, he needed to finish the story before he lost his mind; and the second reason was that he had a family, and he didn’t want his writing to infiltrate his family. I thought that it was somehow close to how I work. Not that I’m an alcoholic – more a workaholic. I tend to go overboard with an idea and I get drunk on that idea. I thought that it would be a strategy to try not to overdo the work. In a way it allows it to have a certain kind of basic system requirement that offers itself as the work. The other thing that I am trying to achieve with my exhibitions as much as possible now is that the exhibition text does not talk about the exhibition. Instead, the exhibition text folds in as a part of the exhibition. Hence, the short story that we send out to everybody also functioned – sheepishly – as a press text. I was quite surprised that there was no major questioning of its function, which also revealed how polite most critics are today.

HY I think that people here think of you as an artist who has affiliations with literature and writing, which is not always the same thing. When you consider artmaking, is there any relevance between the short story and your production? And how does that function in relation to our time here and now?

HC That’s a very good question. I think it’s actually encrypted in how I write. The writing itself is about surrendering oneself to details, rather than trying to explain the circumstances of the story.

HY You are trying to get rid of this idea of the grand narrative.

HC Yes. To get rid of a master plan.

HY For instance, the two pots on hotplates in the exhibition, there is hardly any fabrication process. It is a typical example of how swiftly things can be made for an exhibition, and it’s very close to what we’ve seen around in our contemporary society, full of commodities and related services. Somehow that piece seems like a laboratory experiment for demonstrating the swift and smooth circulation of goods and services, not high science. Did you mean for it to be an ecosystem of those economies as well as ecology, along the lines of entropy?

HC Not actually. The piece is called Boiling Point, and for me it has a cinematic quality to it. When I’m in a relationship with someone, I often spend a lot of time negotiating the relationship through cooking. I also find myself watching things boil, watching things transform into other things. For me, there’s a certain relationship with transference of this state of things in relation to the daily process of cooking – you know, transforming material into food.

I think the work talks about that for me. I thought it would also be beautiful to initiate a process that suggests a certain transformation, which is to boil some water. It is also a sound piece where you hear the water boiling, and a thermoceptic piece in that you can feel heat emanating off the work. There’s something about moisture that appeals to me also: that something is not dry, unfinished. Something that exists in the space where it becomes difficult to talk about.

HY The work is rather far from social commentary with its cynical appropriation. It’s actually quite the opposite.

HC When I started thinking about the work, it came across as a very short process. That it’s really about having a loop in the space that works without a recording. So it’s something that happens over and over again. Which can easily become social commentary when you wrap it around certain contexts.

HY Over and over again? Or continuously boiling?

HC Over and over again. Because the water boils and the pots have to be refilled. There is a stop in between the boils.

HY Is it biographical?

HC It’s about waiting, this sense of waiting for something to happen.

HY Waiting for something to boil down.

HC Exactly. And I always tell people that the idea of the biography is unavoidable. You can resist and refrain from expressing it, but it’s hard to say it’s not a part of you. At the same time, I don’t think we have to consistently inhabit this mode. This balance is important to me. The biographical aspect is also related to where I live. In Singapore you really feel the moisture in the air. I thought it would be an interesting sculptural moment to talk about this humidity.

HY Humidity in Seoul is only seasonal, while in Singapore it’s almost always humid.

HC I think it’s also important for me that the piece doesn’t exist as a sculpture. Artsonje Center knows that after the exhibition ends, they can reuse the table and someone should adopt the pots and the stoves to use them in their home.

HY Is this a principle of every work in the show?

HC Not for all the works. For example, the banner will remain as an object. It doesn’t make sense to instruct someone else to make it. But for Smoke Gets In (Your Eyes), which is the smoking corner, it makes sense not to have someone store away piles of cigarette butts.

HY What if someone collects the work?

HC They’ll be collecting the instruction of how to recreate the work. I would state in the instruction of Boiling Point, for example, that with every re-creation, the owner should also find a new table, new pots and new stoves. It’s the same for Smoke Gets In (Your Eyes), where I don’t think I want to state that the two ashtrays have to be identical. Or that they should be on a table. I would like to keep it very open, so that the piece will always look different in every exhibition. In a way, it’s similar to the moisture. It’s somehow there, you don’t really know what to do with it on certain days; on other days, it’s very apparent how you must encounter the instruction.

HY Based on memory, when you look into the exhibition space, there are fire extinguishers, there are pots of boiling water and there’s a smoking corner. Metaphorically, they somehow build a form of drama, something to do with the sentimental and the sensory.

HC The space that connects the three works actually forms a circle. It’s a very simple way of grouping things architecturally, as if they’re sitting around, having a conversation or just hanging out.

HY Is there any common biographical or sentimental background to all of the three works?

HC To a certain extent. For example, with the fire extinguishers, every time I have an exhibition in Seoul, either myself or the curators would go into a panic about how to hide the extinguisher. I think in this round, what I did was to surrender to the extinguisher. And it’s something that writers do as a technique, even filmmakers: when they cannot finish a story, they surrender, and the last paragraph ends the story on a different tangent; rather like a strange, misplaced punctuation. I’m very interested in these punctuations, as the gaps and stops become part of the constellation. It’s similar to Smoke Gets In (Your Eyes), which was somehow a way for me to involve a smell that is not produced by a machine. I didn’t want to introduce whatever I could have produced mechanically…

HY Why?

HC I think it refers to a kind of senseless accumulation within the space. In this situation, it made more sense to talk about the notion of influence. You smell the scent in the air and you see the pots of cigarette butts, and somehow you are immediately involved in these levels of difference through the simple act of changing the quality of the air.

HY For me, the cigarette smell has nothing to do with the real or synthetic smells. It has more to do with the act of smoking within the building, which is illegal – everything else would be secondary.

HC I did consider that political aspect, but I’ve chosen to push that as a subplot to the situation. If I were immediately to introduce the idea that this work is about what’s legal or not, I’d be pushing people to make a decision. I’d be leaning on the fact that people will make the conscious decision to smoke, knowing that it’s illegal to smoke indoors. I wanted to ensure that visitors are not cornered into making a decision. You don’t have to do it, but you can.

HY If I may elaborate, this work interests me because I’m a smoker myself. Smoking used to be much more existential than social. Now the ban is so strong that both pro- and contra- parties have become highly socially engaged in the discussion. Someone said to me that smoking is the touch of death, you smoke despite knowing that it would harm you. But human beings are not completely reasonable animals, we still engage in things in spite of that. By offering this smoking corner, things are possible – you can consider what to do under less pressure, which is unlike how it is outside the museum.

HC I think it changes your relationship between your body and this exhibition. I always think about the notion of probable choreog- raphy in relation to making exhibitions. Over the last few years I asked myself: why do I still do this when I could just only write short stories? It is a very existential question for me and there was even some point in my life when I thought: I don’t want to do exhibitions any more; I’m just going to focus on writing. However, with this show I found it interesting again to construct these objects, simply because there is still a potential within each object that opens up an intimacy with the audience. For me, writing has a lot to do with describing, with the notion of making a list, in order to make a connection to the described. It’s very close to sitting beside a person, about compan- ionship. A description accompanies the reader also to suggest that the short story is written without any drafts, that it’s mostly improvised. I’m not trying to bring you somewhere, but to propose that you have to go there on your own terms.

HY In a sense I get it, but I think that it’s too general: which piece doesn’t accompany an audience?

HC It’s rather unresolved for me too, but that’s OK.

Artist and writer Heman Chong was born in Malaysia and is based in Singapore. Having represented Singapore at the 50th Venice Biennale (2003), his work has since been included in numerous other large-scale exhibitions, among them the 10th Gwangju Biennale (2014), 7th Asia Pacific Triennale (2012), Performa 11 (2011) and Manifesta 8 (2010). Chong’s Never a Dull Moment was on show at Artsonje Center, Seoul, 7 February – 29 March 2015

Haegue Yang is based between Seoul and Berlin. She represented South Korea at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009). Her work has been included in the São Paulo Bienal (2006) and Documenta 13 (2012), and has been the subject of numerous museum shows. Yang’s Shooting the Elephant象 Thinking the Elephant was on show at the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, 12 February – 10 May 2015