The sounds of protest and resistance produced by women are caught in a political contradiction, as Anne Carson’s The Gender of Sound explores

What does it mean to speak and be heard? Sound – listening, speaking, exclaiming, wailing, music, laughter – intimately binds corporeality with civic life, and the body with politics. Anne Carson’s The Gender of Sound (reissued this year by Silver Press after it was first published in 1992) takes as its subject the gendered experience of sound in its production and reception. Sound, as Carson contends, is an important site where gender is constructed and reinforced; a terrain of boundary demarcation, it is attended by forms of force and exclusion. It is, as Carson tells us, ‘in large part according to the sounds people make that we judge them sane or insane, male or female, good, evil, trustworthy, depressive, marriageable, moribund, likely or unlikely to make war on us, little better than animals, inspired by God.’ Could sound be the fascia or connective tissue that holds together the enduring metaphor of the body politic?

Celebrated for works such as The Autobiography of Red (1998), Nox (2010), and her translation of Sophocles’s Antigone (2012), Carson in The Gender of Sound argues that ‘putting a door on the female mouth has been an important project of patriarchal culture from antiquity to the present day’ – evoking the nymph Echo, described by Sophocles as ‘the girl with no door on her mouth’. Though primarily drawing upon examples from Ancient Greece, Carson’s essay ranges through other moments in Euro-American culture that resonate with her argument, with references to the voices of Gertrude Stein (Ernest Hemingway ended his friendship with Stein because he ‘could not tolerate the sound of her voice’ in an account replete with toe curling misogyny) and Margaret Thatcher (who had elocution lessons to deepen her voice).

In one passage, Carson describes a cry made by women called the ololyga in Ancient Greek, a ‘high pitched piercing cry’ made in climactic moments during religious rituals and life events – a sacrifice, the birth of a child. Carson writes that such sounds – made on the margins of civic spaces, such as mountains, beaches or rooftops – were confined to women, and that ‘no man would ever make such a sound’. There was also, she writes, the religious ritual of aischrologia, the uttering of abuse and obscenities by women. The sounds women produce, Carson writes, are caught in a political contradiction. They are meant to say the unsayable, ‘discharging unspeakable things on behalf of the city’, and in spite (or maybe because) of this, their utterances are controlled and denigrated. In the Physiognomics, it was the high pitch of women’s voices that was used by Aristotle as evidence of their evil nature.

Banished, controlled and the bearers of disavowed truths that unsettle the polis – there is a proximity here between the sounds made by women and the driving forces of mass protest. This sharp edge of political critique drives Carson’s essay. The ololyga that she describes belongs to a time where the voices of women were exiled to the margins of the city. It would be insufficient to simply attach marginalisation and transgression to women’s experience of sound. But the mapping of gender onto sound in the manner that Carson describes persists, and shapes who will be heard, when, and on what terms.

To that end, I have found The Gender of Sound particularly useful when thinking about forms of protest. Languages of justice and political freedom are saturated with metaphors that reference experiences of sound: being silenced or heard; making a noise for what matters; finding a voice. In thinking about Carson’s meditations on gender and sound I returned repeatedly to two images of protest which draw attention to the manoeuvres necessary for certain voices and their claims to be heard. Each in turn foregrounds the gendered experience as part of that protest.

The first is a photograph, widely circulated via newswires online, of a topless protest staged outside the Scottish parliament last month by trans women protesting the Supreme Court’s conflation of the category of woman with biological sex. The protesting women wore black tape across their mouths. The tape signified censorship, but it was also a powerful act of letting the body speak as they effectively conveyed the contradictory violence with which trans women are faced, enduring both a gendered silencing and simultaneous exclusion from a gender category.

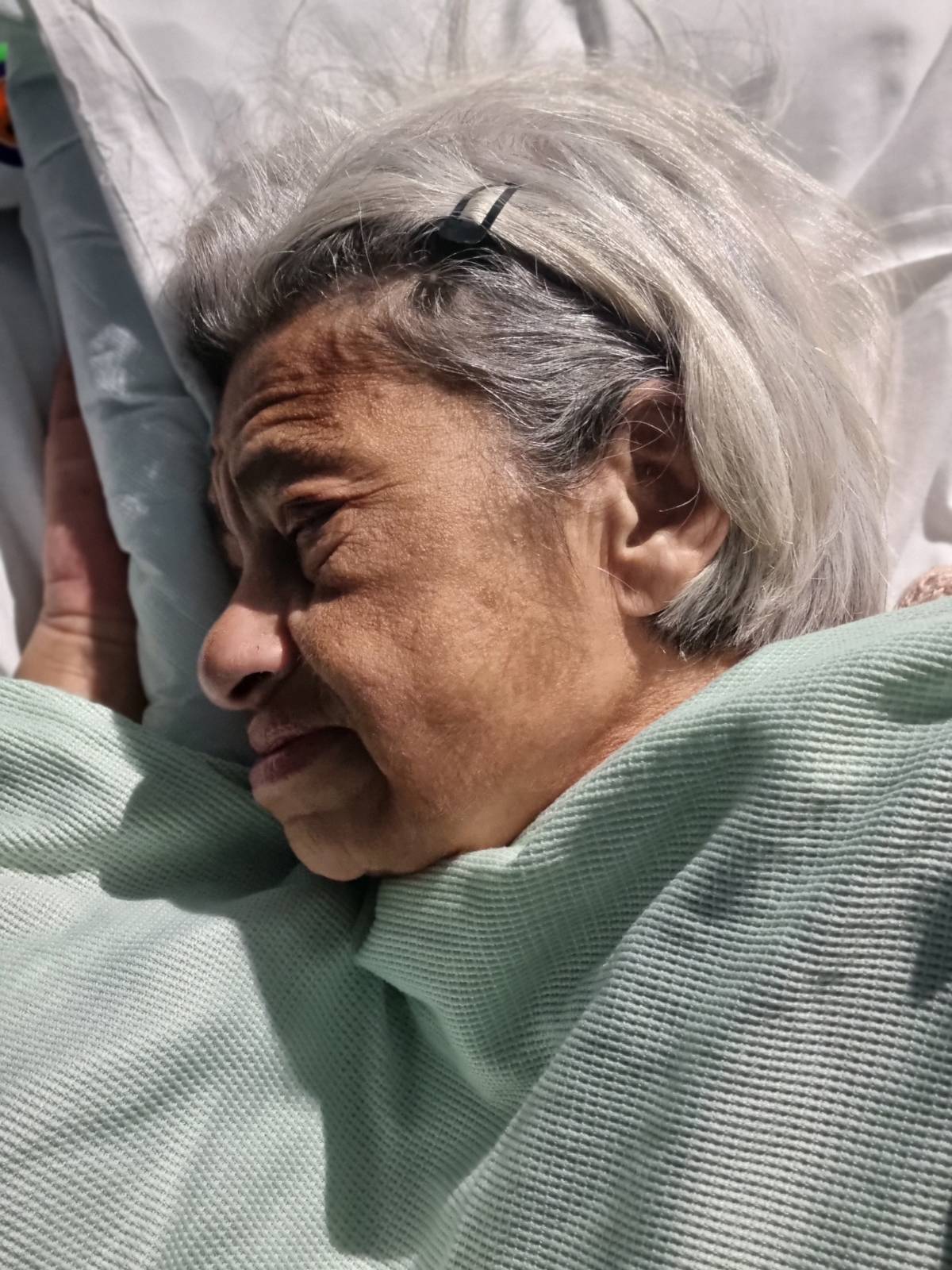

The second is of the mathematician and academic Laila Soueif, on hunger strike since September 2024 to demand the freedom of her son Alaa Abd’el Fattah, jailed in Egypt for his work as a writer and activist. She is currently in St Thomas’ hospital in London, using the very last remaining reserves of fat in her body to continue her protest. Soueif is using every means at her disposal – her voice, her thought, the physical matter of life itself – to address the British and Egyptian governments who preside over the countries in which she and her son are dual-nationality citizens. Soueif’s hunger strike inverts associations between mothering, nourishment and sustenance of life. At the same time, in fighting for her son’s life by giving up the resources of her own body, Soueif’s hunger strike repeats and re-inscribes the gestational labour of creating a life as claim towards political freedom. Some things can be heard without making a sound.

Akshi Singh is a writer and psychoanalyst based in Glasgow and London