The 81st edition, Even Better Than the Real Thing, reflects the biennial’s own function as a time capsule – what do we want to say about our present reality?

Given that the 81st edition of the biennial shares a title with a U2 track with jaunty lyrics that go, ‘You’re the real thing / Even better than the real thing’, you might approach the visual and sound- and time-based works by its 71 total participants – 29 of whom are included in concurrent film and performance programmes – expecting to encounter a barrage of libidinal intensities. Described in its curatorial statement as a ‘dissonant chorus’ inaugurating a future characterised by bodies existing and shapeshifting freely in physical and virtual space, the 2024 biennial seems poised to inherit the formal concerns of its previous iteration, which featured memorable born-digital and posthuman works by Jacky Connolly, Aria Dean, Daniel Joseph Martinez and WangShui.

At first sight, this year’s four-floor presentation, with its minimalist restraint and intimate closed floorplan, suggests more harmony than dissonance. Evidence of a struggle between dominant, reactionary interpretations of reality and the lived realities of marginalised groups takes time to emerge. When it does, however, we see the reality of the latter linked to the notion of historical truth. Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich’s film Too Bright to See (2023–24) pays tribute to the overlooked Martinican theorist Suzanne Roussi Césaire (1915–66). Long takes shot in Miami, in which an actress portraying the thinker stands solemnly among palm trees, reading occasionally from her essays, conjure Roussi Césaire’s Martinique no more than the landscape of her time did: “This beautiful, lush island”, a line from the film reveals, “camouflages the colonial reality”. As a corrective to archival biases favouring those in power, viewers are urged to seek out the narratives of women and colonial subjects buried beneath the visual harmonies of natural vistas.

In Diane Severin Nguyen’s film In Her Time (Iris’s Version) (2023–24), an actress playing an actress in a recreation of the 1937 Nanjing Massacre reflects, “Some roles are far away from my real life. I do a lot of research… I try to recall the films I’ve seen and then I really put myself into them.” Perhaps the past exists only as images, but an empathetically researched reenactment can help recover real emotions. Likewise, in Pollinator (2022), a video about the Black trans activist Marsha P. Johnson (1945–92), the artist Tourmaline strolls in early-twentieth-century attire through cultural institutions in Brooklyn; in A Plot, A Scandal (2023), artist Ligia Lewis dances with spears, parodying racist tropes, then romps around in a period costume on a verdant hill in Italy. These three works reanimate history’s spectres to show how, as Tourmaline asserts in her artist statement, ‘The truth of life is its ongoingness’, or, to quote Lewis’s film, “Ghosts don’t die so easily”.

Considering the biennial’s own function as a time capsule, the curators seem to have asked, ‘What do we want future historians to know about our present reality?’ Accordingly, many of the works on view index the human body’s vast indeterminacy, which we’ve come to recognise via technology and introspection. Jes Fan’s biomorphic sculptures – 3D-printed CAT scans of his leg muscles, spine and stomach – function elegantly as metonymised self-portraits. P. Staff’s portrait takes the form of a wallpaper on which their countenance is at once expanded, dispersed and obscured. Using ceramic body-casts threaded with PVC tubes, Julia Phillips posits parental care as the extension of one body into another, while the invisible hands activating Nikita Gale’s player piano suggest that, through labour, bodies extend far beyond the flesh.

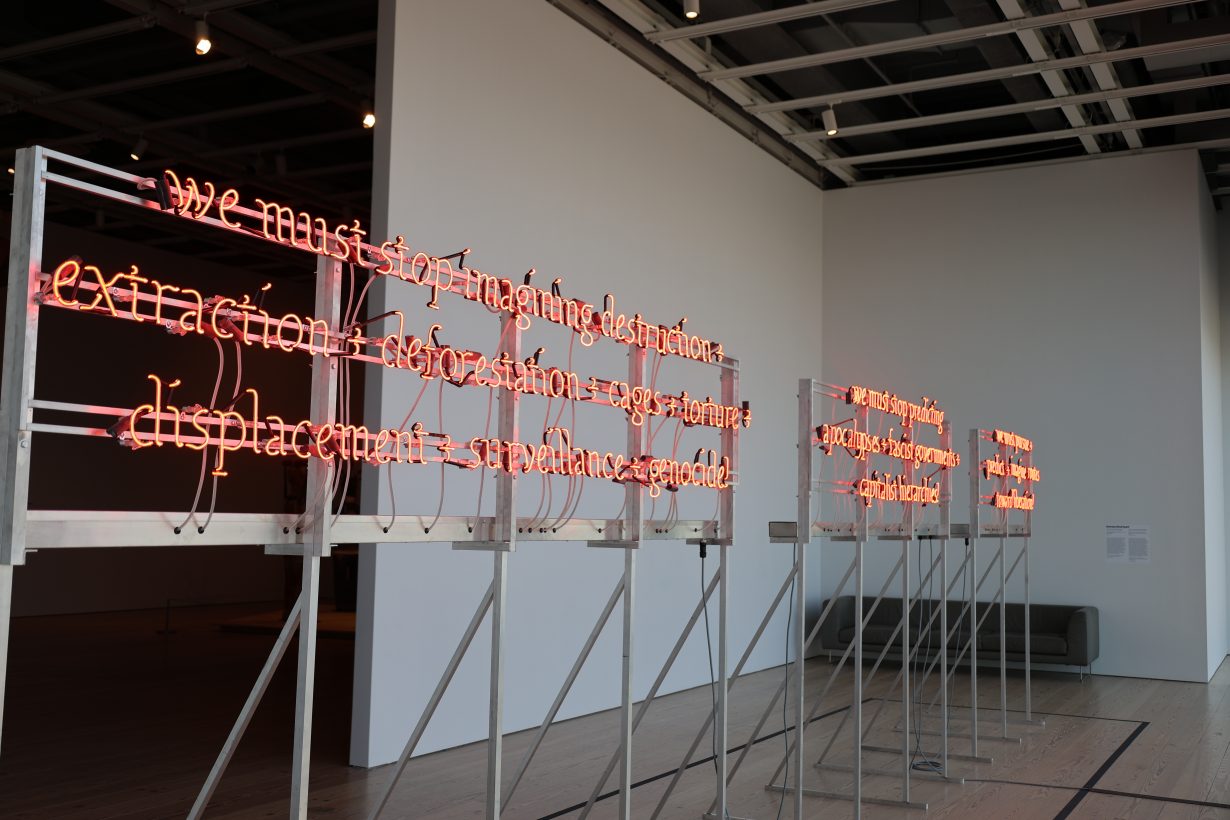

For the future historian, the biennial also registers several of today’s most urgent political debates. A neon sign by Demian DinéYazhi’ spells out a message to ‘pursue + predict + imagine routes toward liberation’ while flickering the phrase ‘Free Palestine’, echoing the demand of activists who have, in recent months, gathered in the streets of New York and institutions like MoMA and the Brooklyn Museum to call out acts of whitewashing and name those with financial ties to the Israeli arms industry. Elsewhere, 2,500 snapshots depicting tasks associated with abortion care, which Carmen Winant collected from archives and clinics across the American Midwest and South, commemorate half a century of legal and ideological struggles for reproductive rights. One sees as well in the strips of photographic film Lotus L. Kang deliberately exposed under ‘wrong’ levels of light and humidity, which hang in a captivating fifth-floorinstallation, and in the expanse of ‘soiled’ junk and paint-spattered tarp that constitutes Ser Serpas’s work in the Whitney’s lobby, the unremitting desire to defy aesthetic norms, a necessary first step, the exhibition suggests, towards envisioning a ‘better’, liberated reality.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 11 August