The luxury to willingly give up a career in the arts is the preserve of a select few. For those artists forced out for financial reasons, there is no choice

Quitting takes nerve. To quit is to simply say no and that you have had enough. It is an impulse that runs counter to everything we are taught to strive for as children: to never give up. Earlier this month Canadian director Xavier Dolan – who directed his first feature film at the age of twenty, was awarded the Jury Prize at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival for Mommy and the Grand Prix at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival for It’s Only the End of the World – announced that he was quitting at the age of thirty-four. ‘Art is useless and dedicating oneself to the cinema is a waste of time’, he told Spanish newspaper El Pais. While he has since reneged on his claim, it is telling that his words were quickly picked up by news outlets around the world, demonstrating not only the collective fear that swirls around the decision to quit but its lasting shock value. Who in their right mind, the headlines seemed to suggest, would elect to walk away from a successful career in the arts?

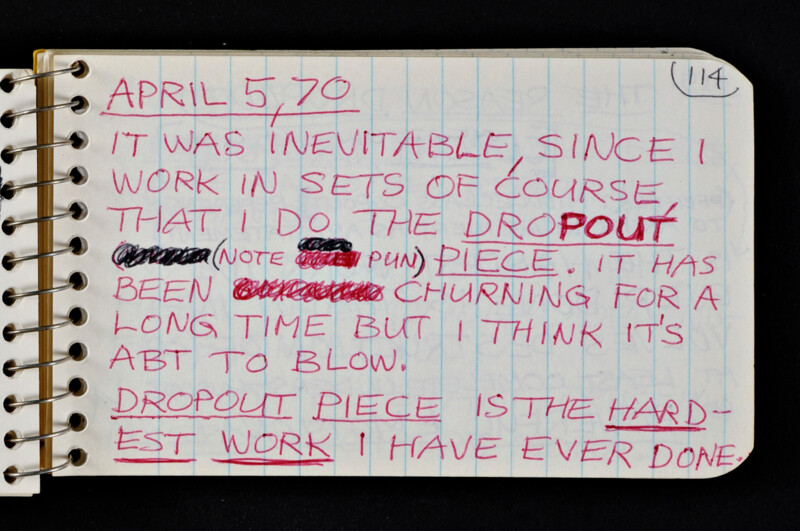

Dolan is not the first to loudly announce his retirement from the arts. Hungarian director Béla Tarr declared his intention to take a step back from filmmaking following the release of his post-apocalyptic feature The Turin Horse in 2011, and went on instead to establish a film school in Sarajevo to make space for a new generation of filmmakers. Others have used the act of quitting as a political statement. When US painter and conceptual artist Lee Lozano announced her formal departure from the New York art world in 1970 with Dropout Piece (the work for which she is now best known), she was enacting a deliberate politics of wider societal rejection. For those who are able to, quitting publicly can be a form of protest as much as a reflection of a wider systemic need for change. Yet as Martin Herbert observes in Tell Them I Said No (2016), an exploration of artists who have withdrawn from the artworld or adopted an antagonistic position towards its mechanisms, the majority of artists will stop working without any statement at all. As in the case of Lozano, the very act of refusal can paradoxically draw greater attention in a rigged system of self-marketing that feeds upon the artist’s own rejection. While quitting can be a deliberate choice, it is often one that only those who have already enjoyed a degree of recognition in their field feel confident enough to make.

Not everyone can afford to quit, whether with fanfare or through silent withdrawal. It is often a privilege defined along lines of gender, class and race; one can dream of walking out on a job for years while knowing that this will never be more than a fantasy that sustains you as you clock in and out. In the creative industries, where the motivations for working as an artist, writer, filmmaker or other creative practitioner extend beyond money alone, quitting takes on a very different meaning. Artists often work long hours for little or no pay as they experiment and attempt to find their voice within an ever-changing cultural landscape. Most will hope to find a route to earn enough in order to live on their artistic practice alone, while the cultural capital and flexible hours of the industry are enough to attract a constant stream of newcomers. A report on artists’ pay in the UK, titled Structurally F-cked and commissioned by The Artists Information Company A-N in May 2023, found that artists can expect to earn a median hourly wage of just £2.60. Another report published by Acme this July presented similarly bleak findings, with artists in London being forced to leave the profession due to lack of funds and a dearth of affordable studio space. For those who simply cannot afford to continue, quitting is not an active decision of refusal. It is often not even a choice.

Only 12 percent of those surveyed by Acme said they could support themselves solely through art. Instead artists must often juggle a paying job alongside their art practice – sometimes for decades or even until their retirement. When working as an artist is not a full-time pursuit, what does it mean to quit the industry? The artworld often trades on stories of artists who have worked in obscurity for decades, with their fits and starts just another twist to the final narrative of success. Artists such as the late Emma Amos and Phyllida Barlow maintained full-time teaching roles throughout their careers, while Howardena Pindell previously worked as a curator at MoMA before moving into teaching alongside her art practice. Day Jobs, a recent exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art, examined the overlooked impact of day jobs on the visual arts and highlighted 75 artists, including Nate Lewis (who worked as an ICU nurse), Vivian Maier (who worked as a nanny) and Mark Bradford (who worked at his mother’s beauty salon) for whom juggling two jobs was a reality of their practice.

While many artists struggle to survive, a question remains not only around public funding for artists but how the arts are valued. This week British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced a proposed crackdown on so-called ‘rip-off university degrees’ that don’t lead to a well-paid, highly skilled job within two years of graduation. It is inevitable that humanities and arts degrees, which promote wide-ranging and critical thinking but are not straightforwardly vocational, will suffer from the government’s cuts to funding, in turn further closing down avenues for young artists to enter the industry. It is a blindspot that is reflected in the limited provision for artists looking to pursue their career full-time, even in the face of evidence that the arts and culture industry contributes £10.8 billion annually to the UK economy. Arts Council England currently gives £445 million each year in grants and funds to organisations and projects across the country, which equates to just under £8 per taxpayer. By contrast, artists in countries with higher tax rates such as Norway can apply to receive an annual salary from the government, giving them the freedom and time to experiment without external pressures.

In the absence of adequate funding, the demographic of artists who are able to stick at it without the financial security of a day job narrows dramatically. An article published this week in the Evening Standard announced the ‘YLAs’, or the new Young London Artists, in a riff on the YBAs (Young British Artists) cohort of the 1990s. Those on the list include the daughter of advertising executive and prolific art collector Charles Saatchi, alongside a property heiress worth £758 million, who offer such sparkling advice for those aspiring to enter the industry as ‘Just do the work’ and ‘Don’t be afraid to fail’. It is a stark reflection of how the meaning of failure shifts depending on just how severe the consequences of it might be when it comes to the personal safety net of wealth. Many others simply cannot afford to take the risk.

The artworld is built on a system of inequality and extremes. Few can expect to get to a point where their work will be financially rewarded into the millions, while most are just trying to survive. The artists who can stick it out due to structural advantages will inevitably have the greater chance of success, but for many the waiting time will be too long for them to maintain. The notion of quitting is at once tantalising and terrifying, a spectre looming over an industry that continues to drive its artists out. It is time instead for the ways in which we value the arts to change. Until the value of these jobs is measured in more than monetary terms alone, and robust support offered to artists from diverse backgrounds, quitting will remain a luxury for those lucky enough to have the choice to stay or go.