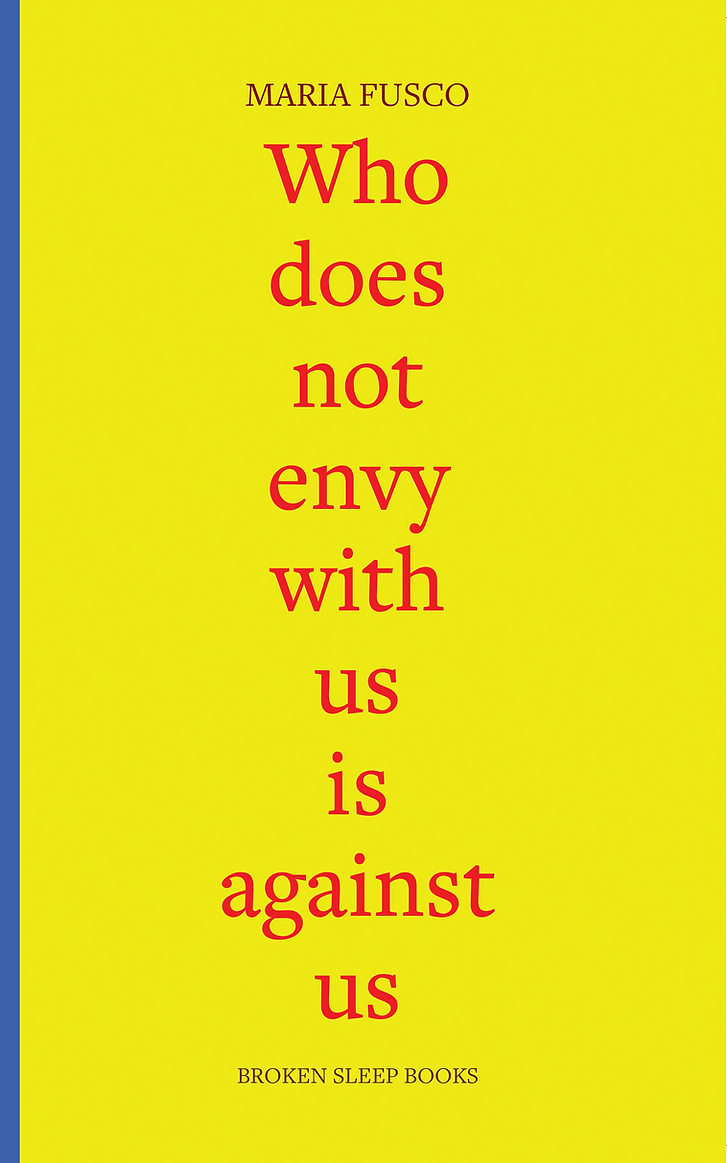

Who does not envy with us is against us examines what a working-class method of critically engaging with the world might be

In the three essays collected here, art writer Maria Fusco outlines the conditions of a ‘working class method’ through reflections on her mother’s engagement with language, listening to the sounds of war as a child and studying performative class-signifiers throughout her Belfast upbringing during The Troubles (and her more recent encounters as a writer and academic). Fusco’s self-reflexive anecdotes frame this examination of what a working-class method of critically engaging with the world might be. And they make for sharp and lively reading. In one example, she recounts arguing with a friend about a television programme featuring a robot protagonist being as important as French arthouse classic Jules et Jim (1962). Because cultural value, she writes, ‘has to do with the analytical eye you are casting over the content, not the content itself ’. And nothing escapes Fusco’s analytical eye, not even her own foibles: ‘so yes, I was sort of patronising them’, she admits. ‘I knew my example was facetious and a wee bit silly.’

It’s entertaining to read slight confessions of frustrated encounters from such a figure as Fusco, whose precise and oddly textured writing often pairs startlingly abject images with rigorous critical analysis. But the ‘analytical eye’ anecdote in the first essay is key to understanding the book as a demonstration of working-class method rather than a compendium of it. Stories of her mother’s flair for insults or a middle-class colleague’s voracious eating habits are more content, as it were, for such an eye to cast itself over in the search for cultural value or meaning. We arrive at understanding how replying ‘stick yer nose up my hole’ to some request or other might have worked to upend the societal servitude expected of her mother’s lower social standing. We come to see how eating four Upper Crust baguettes before and during teaching is a ritual transmogrification of ‘immaterial notions into material bites’ that enables her colleague to be what he needed to be inside the academy, a sort of self-styled alchemist.

Friendly or frank examples invite us to unpick the complexity of images to reveal the intellectual contours of Fusco’s thesis – that yes, working-class experience fosters a way of doing and being in the world, but in the context of writing and teaching, it uniquely shapes a system for evaluating that experience. The working-class analytical eye is trained on starker substances than Jules et Jim. Fusco’s exposure to violent civil unrest through her family’s economic disadvantage, and how this permeates her approach to writing and teaching, is the cord that pulls the anecdotes together into a creative demonstration of a working-class method. In the second essay she tells us that her early ‘relationship with the power of words was predicated on keeping your mouth shut, pretending you did not know something in school… and never ever stating a preference of any sort’. It’s clear how on these constricting terms of communicative operation the anecdote might function as a way of saying and not saying. Like workaday parables, anecdotes are the appropriate vessels to hold and share experiential knowledge without resorting to a pedagogue’s didacticism. Such questions of what working-class experience teaches us and how to make good on what’s learned reverberate in the political girders of the book, standing it in the tradition of a liberatory pedagogy. Accounting for the formative experience of listening to war, Fusco writes, ‘when you’re inside your house and there is a riot… you experience it through sound… each sound you hear has a diacritical relationship to the others: you are learning’. It leaves you wondering: what other experiences of sound, gesture and language in the working-class world might form methods that work to upend such constricting social conditions?

Who does not envy with us is against us by Maria Fusco. Broken Sleep Books, £9.75 (softcover)