A new show at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon invites us to consider the ever-shifting definition of what it means to be ‘post-human’

At the entrance to Human Is in Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon, I’m preparing to be confronted with art that considers how our species is becoming ‘post-human’ because of technological disruptions, when I’m subject to a decidedly unmodern exchange and required to pay the entrance fee in cash. No cards are accepted here, still entirely normal for a country where many people carry within them a deep-seated suspicion of virtual financial transactions.

Inside the exhibition the first work on display is a copy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein accompanied by a small portrait of its author. Perhaps this is supposed to indicate that the exhibition takes its cue from literary sources: its name is the title of a short story by the science fiction author Philip K. Dick, known not only for his depictions of societies in which humans live side-by-side with androids, aliens and robots, but also for his ability to foresee the existential anxiety triggered in us when faced with these almost-but-not-quite humans.

But before anticipating all the ways in which we might become enmeshed in different technologies, Human Is reminds us that our physiological boundaries are already breached by other species; we function as a landscape for bacterial and fungal species which, in turn, we rely on to survive. Nour Mobarak’s Reproductive Logistics III (2023) shows the physical detritus of reproductive treatment: models of flasks, cushions and other everyday items have been seeded with a fungus that is continuing to grow during the exhibition. What is assumed to be sterile and ‘clean’ is here shown to be anything but, the artistic intervention acting as a microscope to make visible what is always there but unseen.

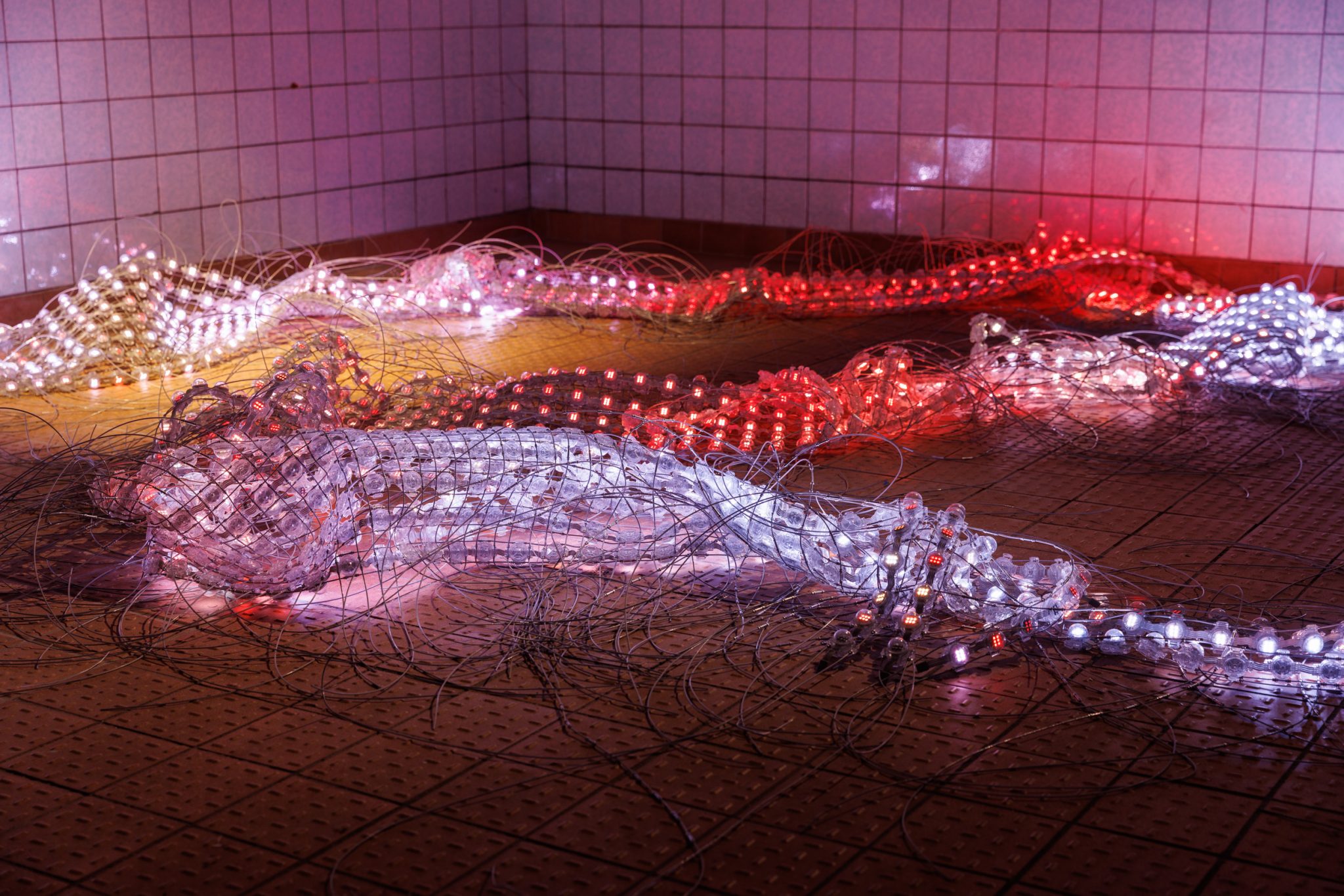

In contrast, WangShui’s Fundamental Attribution Error (2023) is decidedly inorganic, a construction of wire mesh whose amorphous shape nevertheless hints at an organic genesis, and ‘fleshed out’ with LEDs that flash different colours and rhythms according to an AI-generated algorithm. The title is the name of a known psychological effect in which scientists tend to ignore the environment of an entity when observing its responses to a stimulus, and prompts me to consider briefly if I and this piece are responding to each other. The complex pattern of lights – which resembles an attempt to communicate with gallery visitors – is unnerving, as is the setting. The mesh is arranged on the floor of one of the gallery’s smaller offshoots, a windowless space with tiled walls more reminiscent of an abattoir.

Upstairs in a large octagonal gallery, both the setting and construction of Ian Cheng’s animation Emissary Sunsets The Self (2017) initially feel more conventional: a video in which cartoon characters rush to and fro, apparently reacting to provocations in a desert-like setting. But it is soon apparent there is no narrative arc for the viewer to catch onto, this is a simulation of ‘infinite duration’ that never resolves and the sense of almost, but not quite, being able to understand what is going on is increasingly discomforting. The act of watching in any manner starts to feel contaminated in this gallery: it was built here in the East German sector of Berlin during the 1960s and used by the ruling elite, a government who made surveillance of their own people a core aspect of society, entangling it into the everyday. As if mimicking my thoughts, Sandra Mujinga’s Love Language (2) and Love Language (3) (both 2023), two large tentacles made of steel slats like vertebrae, protrude from the wall as if having effortlessly burst through.

This exhibition invites us to consider what might be ‘post-human’, how we might be altering in response to the ebbs and flows of new technologies, machinery and capital. But the definition of ‘human’ has always been subject to revision. Less than a hundred years ago my German-Jewish family were likened to rats and parasites. Only in the past few years have the skulls of hundreds of Herero and Nama people been repatriated to Namibia from various German museums and hospitals – where they were subject to supposedly ‘scientific’ experiments. Matthew Angelo Harrison’s Touched by an Angel (2021) consists of a West African statue imprisoned in industrial resin, literalizing our metaphorical inability to view this object other than through our modern sensibilities. The confrontation of what is commonly defined as ‘traditional’ art with the industrialised space-age society is also evident in Alexander Kluge’s and Sarah Morris’s Cats in Space (2020), which interweaves documentary footage of cats being used as test subjects in early space age experiments (by both the Soviet and the French space programs during the 1960s) with that of ancient Egyptian cat mummies who were considered to be representatives of gods from space. Their modern space adventures, the video suggests, are just returning them to their origins.

Cats in Space has an educational quality to it also evident in the foregrounded copy of Frankenstein, a reminder that our concerns about the influence of technology on humans almost exactly coincide with the rise of industrialisation; Shelley’s novel was first published in 1818 during the era of Luddite riots and widespread attacks on industrial machinery. Workers, whose livelihoods were threatened by the new-fangled devices, targeted the Jacquard looms, machines that pioneered the use of punch cards in producing complex patterns on the woven cloth, thus replacing an essential component of the workers’ skills. This same technology later became a core aspect of the first generation of programmable computers developed in the 1940s. At this time Alan Turing developed his test for artificial intelligence which configured it as imitation: can we be ‘taken in’ by a computer behaving as if it’s human? This link between machine logic and metaphor goes deep, the power of computers lies in their ability to manipulate symbols which can be used to represent other entities. In Philip K. Dick’s story Human Is, the alien secretly impersonating the human is subsequently exposed through its use of rich metaphors, which it learned from reading books. Information theory tells us that all knowledge can be configured as a series of 1s and 0s, and considered a separate entity to the substrate which stores and transmits it. But Human Is reminds us that formulations of the future rely on its essential – and inescapable – connection to the past.