The appeal of the clinical psychologist turned right-wing celebrity guru’s new book Beyond Order

In their myths, the ancient Hitterians used to tell the story of two brothers, Jah-Dan and Petah-San. Jah-Dan and Petah-San were twins, the sons of the mother-goddess Can’Adia – but they were the product of different fathers. Jah-Dan was the son of Normal, the king of the heavens, the Wise King who represents Order. But Petah-San had been beget on Can’Adia by Redan’Nud, the king of the underworld, and Lord of Chaos. The brothers grew to adulthood, and Jah-Dan lived modestly but well: he lived on his prosperous farm with his wife and children, and on feast days always honoured the gods with sacrifices. But then one day, Petah-San showed up at his door. Petah-San poured scorn on Jah-Dan, and told him that in truth none of the good things he had in his life mattered, because he lacked the most important thing of all: fame.

And so Jah-Dan abandoned his family, and followed his brother out into the world. Whenever the two reached a settlement, Jah-Dan would give a lecture: a strange, angry lecture, about how no-one these days was working hard enough, about how pronouns meant we were the Soviet Union, and how all those no-good kids needed to get off his lawn. Jah-Dan’s words made the people very happy: by listening to him, they could believe that all the bad things in the world weren’t the fault of the people in charge, but of the useless young people, who were always complaining. They showered Jah-Dan with riches, and began to speak his name throughout the land.

But then strange things started happening. Jah-Dan’s crops were eaten by locusts, and his business was ruined. His family contracted a mysterious illness, and Jah-Dan himself began to wither away. He started getting smaller and smaller, and his voice grew weaker and weaker, and started to sound like Kermit the Frog. And all the while, Petah-San started getting stronger and stronger. He started to replace Jah-Dan on stage. Eventually, Jah-Dan had become so small, and Petah-San so big, that Petah-San was able to eat Jah-Dan up, swallowing his brother in just one gulp. The son of Order had been consumed by the son of Chaos – destroyed by the desire for fame.

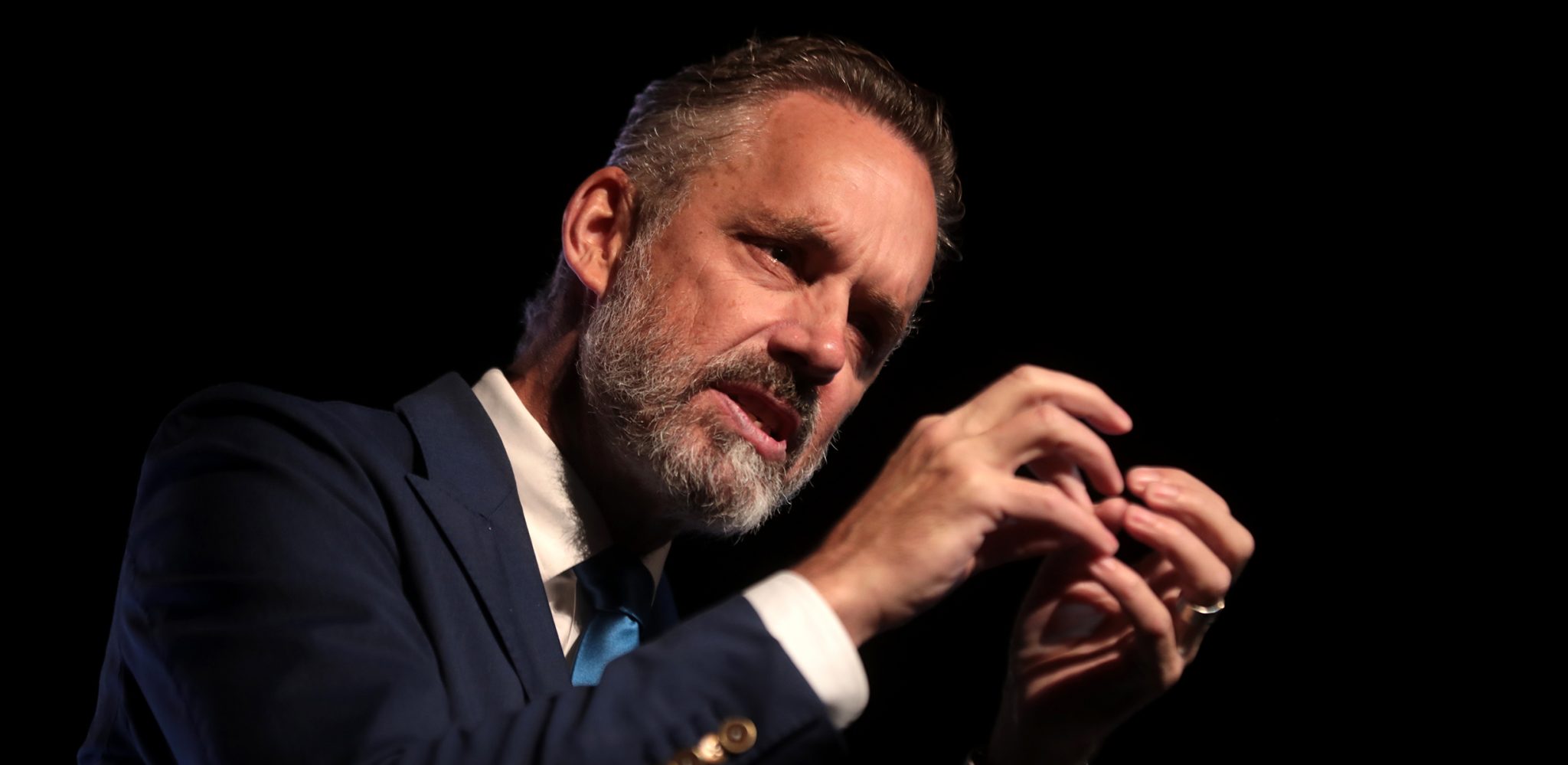

Jordan Peterson’s new book Beyond Order: 12 More Rules For Life (2021) is full of little fables: from ancient mythologies, from the Bible, from Disney films, even from Harry Potter (at one point Peterson spends a good three or four pages describing the rules of the wizard game Quidditch). The Quidditch thing at least clears one mystery up: yes, Peterson is now successful enough that he has been able, J.K. Rowling-style, to largely slough off the need for an editor. But none of these stories ever come close to addressing what are, for me, the two central mysteries of his work.

Mystery 1: just why would someone like Jordan Peterson do this? Why would a man who up until a few years ago was a tenured Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Toronto, with a happy marriage, a thriving private practice, and a growing collection of Soviet Realist art – the very definition of quiet, but meaningful, success – risk it all to become an internationally famous self-help guru? Especially when we now know that this story ends with our hero strung out on benzos, subsisting on a diet of only steak, salt and water, his life spiralled out of any semblance of control… awakening last February in a hospital in Moscow from a medically-induced coma, that he had been placed in by his fad diet influencer daughter.

Peterson purports to tell us how to live, despite all the hardships and sufferings of the world. Going by the evidence of the ‘Overture’ which opens this book – in which he tells his side of the reports about his health which originally surfaced early last year – he has certainly experienced his fair share. I wouldn’t want to make light of them – I wouldn’t wish what has happened to him or his family on anyone, no matter how fervently I might disagree with them. But given everything – given how extreme Peterson’s health problems have been, and given that this book was by his own admission mostly written before they ultimately came to a head – this can all feel a bit like Sideshow Bob deciding to write a book telling us how not to keep stepping on rakes.

This brings us to our second mystery: just what is Jordan Peterson’s appeal? Everything else about him aside, this is not a book that contains much in the way of real, practical advice. The 12 ‘rules’, such as they are, veer wildly between simple mindfulness exercises (‘If old memories still upset you, write them down carefully and completely’) and profound-sounding nonsense (‘Do not hide unwanted things in the fog’). But then, this hardly matters – since whatever the rule is, Peterson’s elaborations, which take up anywhere between 20 and 50 pages, tend to bleed into each other: covering the same thematic ground to the point that by the end, it’s hard to remember which rule you’re now reading, and which you’ve just left behind. A story from a fairy tale where he tells you what all the archetypes are by Capitalising Their Names here, a laughably one-sided reading of a big-name philosopher there, a weird boast (did you know that Dr. Jordan B. Peterson believes that he has seen more art than any other human being in history?)… you get the idea. The only really engaging bits are when Peterson tells stories from his clinical practice – which tend to at least be lucid. Why do so many people look to this guy for answers? What do they believe he’s giving them?

Here, as far as I understand it, is the personal philosophy that Peterson espouses. If we exist, then suffering is inevitable. We can never eliminate the tragic dimension of life, and we are always vulnerable to it. We should not therefore pursue happiness – we should pursue meaning (we can be happy, but this is only possible as a sort of capricious by-product of the struggle for meaning – we might get it or we might not). We all ultimately stand alone before God: as adults, no-one will be, or should be, responsible for us, so we need to take responsibility for ourselves. Despite this, we are also socially dependent: humanity is locked in an endless struggle with an ultimately unknowable and unconquerable nature, so we need to band together if we are to survive.

Any healthy society must find the right balance between conservative forces, to preserve tradition, and creative ones, to transform it when necessary – though to change tradition you ought to have a firm grounding in it first (new techniques in art are invariably pioneered by people who have mastered the old ones). Young people should, therefore, be modest – and work hard. They should value their family, and seek to start their own if possible: Christian (and especially Protestant) values have a solid evolutionary basis, and we can know this because they figure in basically every story we tell ourselves. They should be willing to make sacrifices – to do boring or difficult things, that they don’t really want to; to shut up and get on with things – both for the sake of themselves, and for the social whole. This, typically, is how a meaningful life emerges. Granted there are exceptions – some people find themselves called heroically to higher things, and in that case the rules as they normally exist don’t really apply. But these individuals, as we know from history, are rare.

It is in this philosophy that Peterson’s appeal as a self-help author is founded – but not necessarily because his followers think that his advice is something they need. In ‘The Stars Down To Earth’, his 1952 essay on the horoscope section of the LA Times, Theodor Adorno noted a certain dissonance between the perceived addressee of the predictions, and the people who were actually reading them. The horoscopes, Adorno deduced, were written as if they were intended to be read by a figure that he called ‘the vice-president’: young, male, a sort of high-flying junior executive – comfortably off, with many important responsibilities, but also a constant array of nagging concerns about keeping up appearances, achieving romantic success, or climbing the corporate ladder. But the section was actually read, for the most part, by lower-middle-class women. The inflated importance of the perceived addressee was thus, Adorno surmised, intended as a device to flatter their egos – to make the readers feel as if, from the perspective of the stars, their modest lives unfolded on the same stage as those of the genuinely powerful.

Peterson, as far as I can tell, has built his public career on pulling off a similar trick – but in reverse. The perceived addressee of his self-help (we’ll call him ‘Bucko’), is someone young and useless: directionless and depressed, dissatisfied; perhaps unable to get out of bed. He (it’s usually a ‘he’, but one suspects it is also sometimes a girl with blue hair) feels insufficiently loved – by his parents, by any prospective romantic partners – and feels as if the world is failing to yield any adequate opportunities for him. But, while Peterson’s audience certainly does appear to contain a high percentage of angry young men, I do not get the impression that young Bucko is who he is really helping. Rather, the perceived addressee is the sort of person his audience fears they might be, and wishes to assured they are not. (For older readers I think this probably works more like: Bucko is who they know their kids to be, and they want to be told it’s OK to hate them). By reading Jordan Peterson, or going to hear him talk, his audience are given a sense of their own superiority: they are not the people responsible for making the world go down the toilet, by failing to knuckle down and get on with things; they are not the people poisoning our institutions by trying to get everyone else to subscribe to the Stalinist woke dogma they have bent their will to. They might even be the sort of special hero who gets to transcend all this stuff. They are valid, and their sufferings are real – it’s the petty complaints of everyone else that are not.

Like any good religion, then (just think about what Christian religious ceremonies actually consist in), what Peterson ultimately gives his audience is the assurance that while sacrificial rituals are indeed taking place to please the gods, they themselves are excepted from having to participate in them – they, as individuals, will never be the victim. It’s the other people – the people who are not submitting properly – who ought to be made to.

And this can also help us solve the first mystery as well. Because if Peterson has a problem, really – if he has a weakness, as a self-help author – it is that he actually believes what he says. Granted his sincerity has also helped him, in a way: it is on the fact that he actually means what he is telling us that his strange but definite charisma is founded. But it also means that by his own lights, Peterson can only be excepted from the sacrifice if he is able to lay claim to some special, heroic calling. And of course this calling can’t be ‘living quietly as an academic’ – it has to be something bigger than that… like, you know, becoming an internationally famous self-help guru. A calling he appears to justify in this book with the suggestion that the PC gender ideology he was first launched to fame by resisting, constitutes a profound political crisis. (That he appears to believe all this may admittedly leave us with the still deeper mystery of how).

Against Peterson, I would present the maxim that I have found myself, in my own life, living by: Adorno’s claim in his essay ‘Progress’ (1962) that the real meaning of his title concept ought to be ‘the hope that things will finally get better, that people will at last be able to breathe a sigh of relief.’ This, I believe, is what we ought to strive for. But it is not something that we can ever really achieve as individuals. I would love to be able to live the sort of life – quietly prosperous, comfortably upper middle-class – that Peterson used to have. Living it would feel, I can only imagine, like finally being able to breathe that sigh of relief. But in truth, I would know that something is wrong: that there would be no justice to the fact that I was able to live like that, when so many other people spent their lives suffering so much for so little. I would never be able to live comfortably with that fact: I would feel constantly insecure. Peterson, I suspect, sensed this – he talks in his book about how in his old life, he was already reliant on medication to combat his anxiety and depression. But while the realisation of suffering may be the beginning of wisdom, he has as yet failed to see the right way to alleviate it.

Peterson, and his followers, are too much in the business of seeking exceptions for themselves. But in truth, the only way that the endless procession of sacrifice and suffering which characterises human existence might be brought to an end, is if we found some way to abolish it together. Real hope is something that can only be worked jointly. The individualistic, heroic view of life is a counsel of despair.

Tom Whyman is a philosopher. His book Infinitely Full of Hope: Fatherhood and the Future in an Age of Crisis and Disaster (2021) is published in April by Repeater.