Age verification and data collection require there be no slippage between who governments think we are and who we want ourselves to be – which was the whole point of the internet in the first place

The UK just became one of the first countries to implement age verification by passing the Online Safety Act, which requires platforms that host porn or otherwise ‘harmful’ content to verify users’ age. Similarly, just a few weeks ago, the US Supreme Court decided that age verification does not infringe on the First Amendment right to free speech (which has historically also protected access to free speech online) as long as it intends to restrict minors’ access to ‘harmful’ or ‘obscene’ material. As Emma Roth reports for The Verge, policies like these are impossible to implement: platforms either quit the country, invest significant resources into building out their own verification process or outsource to a third party that will inspect users’ government ID, credit card or other details to determine age. All of this is of course easily outmaneuvered by anyone using a VPN to spoof their location. Policymakers often consider the fact that you can be anyone you want to be on the internet – a rich heiress or a Nigerian prince – one of its major vulnerabilities. They focus on all the ways the gap between online and offline can be exploited by scammers, catfishers, impersonators, traffickers and other agents of chaos.

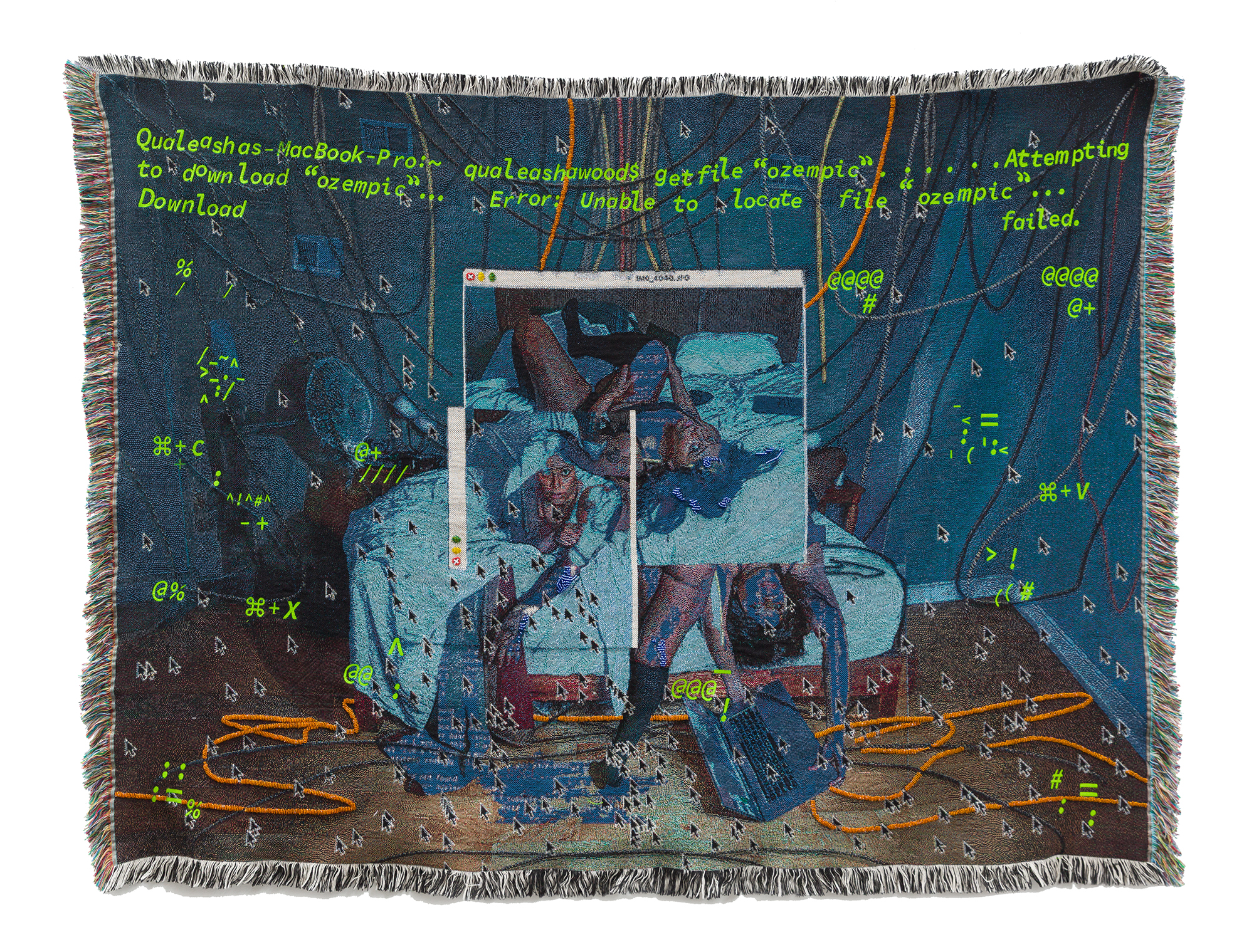

The early days of the social internet, however, thrived on aliases and avatars. Anonymity was the rule and identities were obscured to make room for a revolving door of virtual selves. Legacy Russell chronicles the unique thrills of the screen name in her introduction to 2020’s Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto: ‘online I could be whatever I wanted. And so my twelve-year-old self became sixteen, became twenty, became seventy. I aged. I died. Through this storytelling and shapeshifting, I was resurrected. I claimed my range,’ she writes. ‘I toyed with power dynamics, exchanging with other faceless strangers, empowered via creating new selves, slipping in and out of digital skins, concluding that, “in chatrooms I donned different corpo-realities”’.

Today, it’s socially unacceptable – often criminal – to misrepresent your identity, appearance or lifestyle on any kind of internet profile. Yet we all reinvent ourselves when we bring ourselves to the internet: the very design of platforms like Instagram or YouTube offer opportunities to remake ourselves with every post and have conditioned a generation of users to show up to the internet as our almost-real selves. We know that nothing on the internet should be taken at face value, that all assertions of fact should be taken with a grain of salt, that people only share what they want us to see, and it is this indeterminacy that makes the internet a worthy social endeavour. In the attention economy, speculation fulfills a dual role: it fuels the engagement machine that’s stimulated by the exaggeration, embellishment and sensationalisation the internet inspires; then it becomes an investment in and of itself – speculation in the simplest financial terms. Every post is a chance to make ourselves out to be hotter, richer or cooler than we really are – if only by deciding what we do or do not post – and every post drives us deeper into the assembly line, recruiting us as content creators to produce engagement in exchange for creator funds or advertising dollars. Demanding we verify our identities and flesh out our profiles keeps the wheels greased.

In her forthcoming book, Amateurs!, Joanna Walsh writes that early social media ‘became increasingly predicated on the implied presence of a verifiable individual or entity’. She details how ‘a profile suggests the limiting concept of the single autonomous personal creator’ and ‘the demand that these profiles be traceable to actual humans has, for better or worse, become a given – as has the collection and sale of personal data’. Big Tech and policymakers claim identity verification makes the internet safer and more efficient, offering little consideration to the fact that these ID verification services are far from being able to guarantee your data is secure, creating a honeypot of licenses and other sensitive documents that are already being routinely hacked. And as Roth reports, the rise in age verification-blocked content on the internet creates the perfect condition for censorship and surveillance, with the chance that undocumented individuals might find themselves unable to access content online. ‘Right now,’ Roth writes, ‘there just isn’t any clear-cut way to verify someone’s age online without risking a leak of personal information or hampering access to the internet.’

Major platforms have long been moving towards making it much harder for us to avoid establishing a singular and definitive online presence. Facebook probably led the charge by requiring a college email upon sign up when it first came out. I remember noticing that as I grew into my late teens and early adulthood, having anything other than my real name on any kind of email or profile was an embarrassing holdover from a bygone internet era. As a college student, I was advised to upload my face to the internet as often as possible to make myself more appealing to the algorithms, to use my given name on all my social profiles and format myself consistently across the internet to ensure mine are the first profiles to come up when a future employer looks me up on Google search. If you Google me you will find all of me, and if I ever decide to make myself less legible to the internet, I stand to lose one of the few capitalisable assets a freelance writer has: her name and her audience.

A solid and verified online presence has now become part of the tax we pay to the internet’s rentier class – the platforms, who’ve grown egregiously comfortable with tying their service’s functionality to the amount of information you give them in the form of identity verification and profile completion. When Twitter/X launched government ID-based account verification in 2023, it did so in exchange for benefits like ‘prioritized support’. Taking the AI and metaverse accelerationism as a cue, it’s clear that, if platforms have their way, our ability to create, use and maintain an online presence – already a near requirement for most instances of work and leisure online – will become a set of protocols they control and rent to us in exchange for our time, data and money. Handing over copies of our government-issued ID will give them supra-governmental access and power over our information, and by extension us.

Thankfully, there are better ways to enjoy the internet. Everything worth doing online is done behind whimsical screen names and jokey avatars: write and publish fan fiction, organise, deal in Neopets cheat codes, spiral on Gaylor (gay Taylor Swift) Reddit, pursue sex work, run a popular meme account or maintain a finsta you only share with a small group of friends. These are all examples of how real people I know take advantage of the ways they can fracture off their identities by refusing to groom a singular online presence. The stakes are lower and you can get away with a lot more. You stand to lose less from the rising tide of enshittification when you make yourself harder to track online.

In his infamous text ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’, John Perry Barlow addresses ‘the weary giants of flesh and steel’ with a warning: ‘Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here.’ And while the internet is far from immaterial, it plays by modified rules that extend the realm of self-creation into a virtual space that appends itself to our social and economic lives. A profile should only ever be one among several portals we provide ourselves – an alias or avatar that indexes the presence of a specific user on the other side of the screen, a meeting place between willing peers and mutuals that doesn’t require such specific performances of the self. A bit of wiggle room to reinvent ourselves whenever we log on.

Michelle Santiago Cortés is a writer and critic based in New York