Accusatory in tone, this show at ΕΜΣΤ Αthens frames the mainstream animal rights debate within a wider context of human conflict

Distinguishing itself from the current fashion for big exhibitions that celebrate a holistic view of humanity’s ‘entanglement’ with nonhuman entities and ecosystems, Why Look at Animals? offers a narrower rhetorical starting point, that of the ethics of human society’s relationship to animals. Borrowing its title from art critic John Berger’s polemical 1977 essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’, this huge show, curated by EMST’s director Katerina Gregos and assembling sixty or so artists, draws on Berger’s preoccupation with looking and the complex moral reciprocity that is inferred by the gaze of humans on animals, and vice versa.

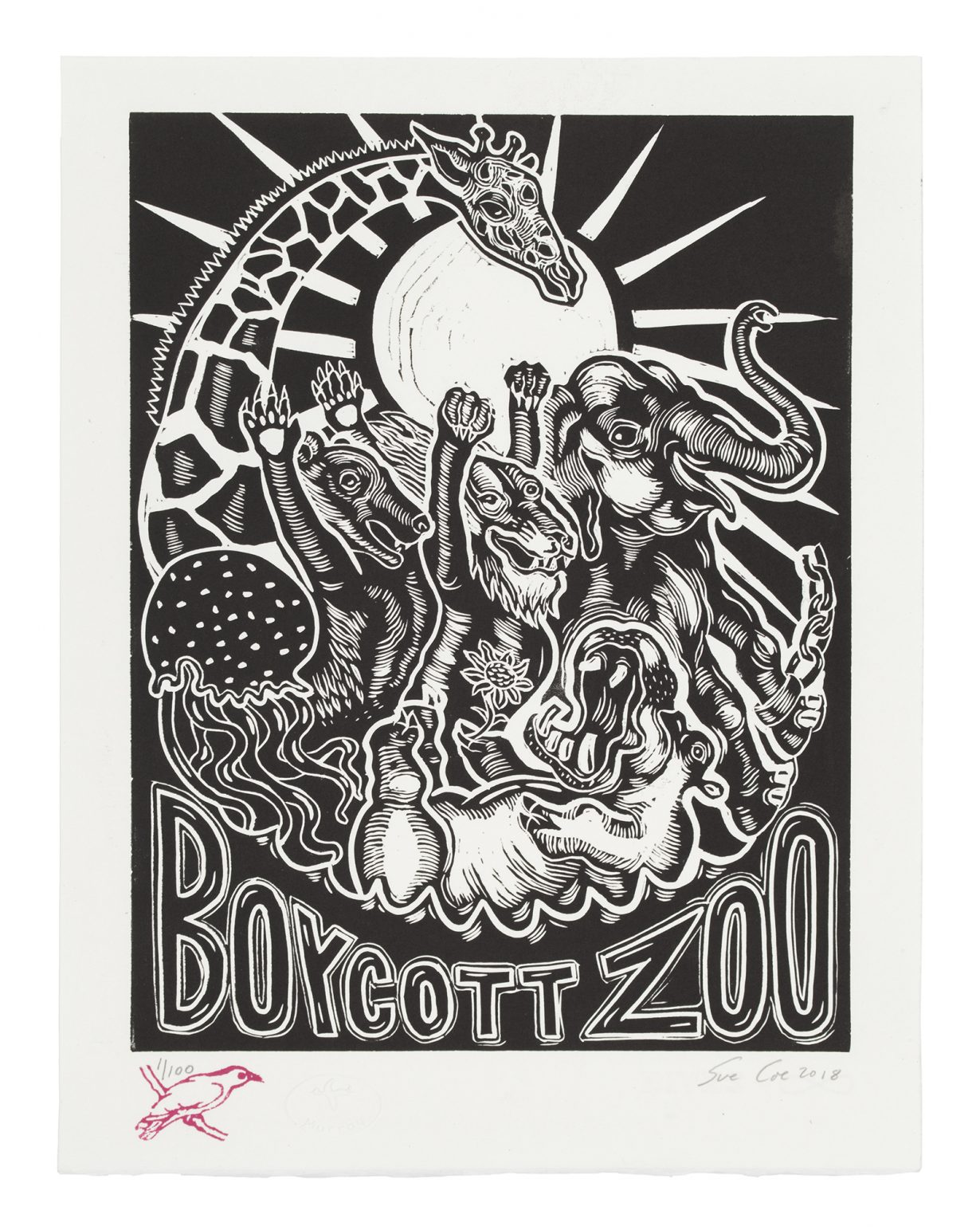

That the show takes the rights of ‘non-human animals’ as a moral issue – rather than, say, a more scientifically driven ecological approach – gives much of it a strong animal-rights activist tone. There are a good few banners and agitprop-like works: cheery, naive embroidered scenes in Ukrainian Jakup Ferri’s installation We We (2011–24) offer a utopian (or maybe pre-lapsarian) hippie-ish vision of people living in equitable harmony with their animal peers; women caress happy caterpillars, families sleep side by side with companion dogs, while animals take on human habits and cultural characteristics; in one tapestry, a humanoid rabbit in high heels dances ballroom-style with a similarly anthropomorphised dog. But the broadly accusatory tone of the show is set by the woodcut images of longtime animal rights activist and artist Sue Coe; here are scenes of relentless bleakness and horror of the human use and abuse of animals, and none better capture the ethical and philosophical issues at stake than Coe’s 2009 print Auschwitz Begins Whenever Someone Looks at a Slaughterhouse and Thinks. In it, cruel whip-wielding humans drive panicked cattle and pigs towards the butcher’s knife, while beyond the compound’s wall rise the glowing arches of the McDonald’s logo.

The phrase of the title, which winds across the top of the print, is completed by the words ‘they are only animals’. The moral reversal demanded is ambiguous: ‘treating people as animals’ is one of those historical prohibitions that come out of the Enlightenment notion that all humans are equal, while the Nazis went to great lengths to characterise Jews as rats and vermin, and such dehumanisation always lies at the core of the racist mindset. But Coe’s slogan demands something else – no longer privileging human life over animal life, and according animals the same rights humans claim for themselves.

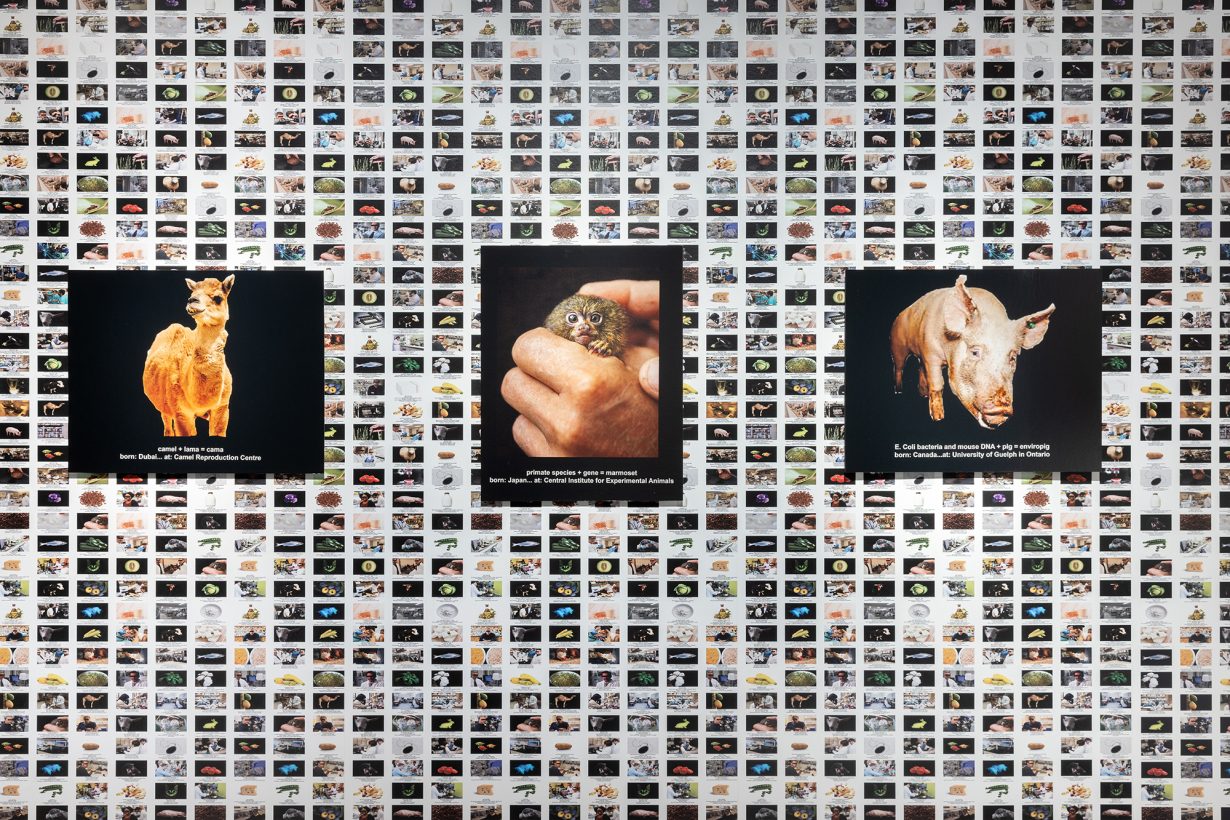

Elsewhere in Why Look at Animals? that demand leads to works that rehearse a steady contempt for humans’ wanton uses of animals, though these may only properly resonate with a viewer whose mind is already decided on these questions: Mark Dion’s Men and Game (1998) is a wall full of framed photographs of grinning (mostly white) men posing with their dead prey in different national contexts – feather-capped mittel-Europeans with their deer and grouse, African big game hunters with their lions and wildebeest; Jonas Staal’s installation of backlit photographs (Exo-Ecologies, 2023) commemorates the mice, rabbits, dogs and monkeys used (and mostly killed) as test subjects in early space exploration, and Lynn Hershman Leeson’s similarly accusatory installation The Infinity Engine (2014) presents images of various animals that resulted from genetic experiments (glowing mice, for example), the strong implication being one of humanity’s recklessness and overreach in its control over nature. And in case the point hasn’t got through, in an upper gallery Maarten Vanden Eynde’s Homo stupidus stupidus (2008) is a collection of reproduction human bones rearranged into a bizarrely sinister mess, presented on a low, reflective black podium. Surrounding Stupidus is Nabil Boutros’s Celebrities/Ovine Condition (2014), a sequence of photographic portraits of ewes, lambs and rams. Can sheep look at humans knowingly? It’s certainly the effect of Boutros’s subjects as they here seem to gaze at the mangled remains of foolish humanity.

Clearly, Why Look at Animals? commits itself to a critique that ties the human use of animals to a bigger indictment of industrialised society: factory farming is deftly targeted in Ang Siew Ching’s video projection High-Rise Pigs (2025), which circles in and around the activities in a pig-farming building in China’s Hubei province, a huge 26-story building in whose closed cycle pigs are born, raised and eventually slaughtered for consumption. What underlies the show’s ethical narrative – a point critical to Berger’s essay – is that modern humanity has become ‘estranged’ from a more ancient sense of reciprocity with animals. That reciprocity is retrieved, to some degree, in some other works; Janis Rafa’s sumptuously gloomy three-channel projection The Space Between Your Tongue and Teeth (2023) attends silently to the activities thoroughbred horses are put through in their stables, particularly in huge, merry-go-round-like running machines. These scenes are freighted with a vaguely S&M eroticism, a sense both of control of and fascination with the horses’ bodies, and which culminates in a scene in which naked men gather to wash themselves and the horses they attend to. In a lighter mood, Annika Kahrs’s video Playing to the Birds (2013) sees a concert pianist in a baroque room play Liszt to an assembly of caged birds, who chirp and sing in response.

Such uneasy reconciliation doesn’t last long though. Emma Talbot’s huge darkly psychedelic painting on silk Human/Nature and video animation You Are Not the Centre (inside the animal mind) (both 2025) attempts to decentre anthropocentrism by articulating a view of human society from the animal’s perspective, but Talbot’s animal characters end up ventriloquising human self-disgust – ‘you smell of a sickness only you have’, thought-bubbles a dog; ‘humans normalise entrapment and ownership’, declares another caged bird.

Berger wrote ‘Why Look at Animals?’ at a moment when the Western Left’s rejection of capitalism was shifting away from class politics towards a more totalising environmental critique of industrial society as such, and with it a bigger philosophical rejection of human exceptionalism. That development has since gone mainstream. But the emphasis on nonhuman sentience as a source of ethical rights is always going to produce contradictions, since only humans have ever invented the concept of rights, and demanded them for themselves. Rights are political, not natural, something touched on by one of the show’s more complex and far-ranging works, Sammy Baloji’s installation Hunting & Collecting (2015). Baloji assembles framed pages of historical photographs from colonial-era Congo (often of servants having to hold up dead trophy animals for the amusement of an implied colonial photographer), superimposed with contemporary photojournalism of soldiers fighting in recent conflicts in the DRC. The whole double-height of an adjacent wall is filled with the names of over 300 NGOs operating in the DRC, no doubt a fair few of them ‘human rights’ organisations. Cynically, one might wonder what good these do-gooders are really doing. In the context of Why Look at Animals? Baloji’s broader attention to human conflict and domination reminds us that, even now, not all humans are equally responsible for the denial of rights, human or otherwise, and poses the problem of whether – recalling Sue Coe’s images – human and animal being can or should be equated.

Why Look at Animals? A Case for the Rights of Non-Human Lives at ΕΜΣΤ, Athens, through 15 February 2026

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.