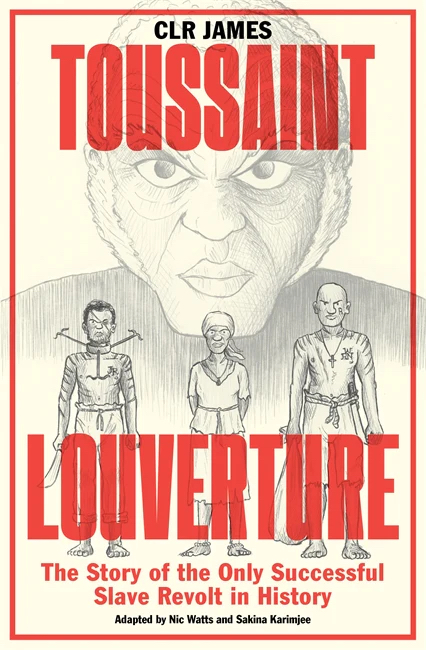

A graphic novel on the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture gives a new view of a welcome addition to a wider reconsideration of colonial and postcolonial histories

Toussaint Louverture wasn’t a part of the history I was taught at school. (In Britain during the 1980s, in case you were wondering.) Instead, I came across him, and the history of the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) later, through the works of painters such as Jacob Lawrence, Kimathi Donkor and Lubaina Himid. In that sense (that of my ignorance) this graphic-novel adaptation of C. L. R. James’s 1934 three-act play (the script for which was recently rediscovered) is part of a welcome addition to a wider reconsideration of colonial and postcolonial histories. It’s notable that the vast majority of books cited in the endnotes to this volume were published after 2000.

Born in Trinidad, James was a lifelong Marxist, a pioneer of postcolonial literature and, in 1936, the first Black West Indian to

have a novel (Minty Alley) published in Britain. Toussaint was born a slave in French Haiti (then Saint-Domingue) towards the end of the first part of the eighteenth century, when the island was split between the French and the Spanish. He became a free man, was the best-known leader of the Haitian Revolution, fought with the French following their revolution, but died in a French jail in 1803, just under a year before Haiti became independent.

‘Surely it [the French Revolution] puts ideas into their heads’, remarks one French officer of what might be suggested to Haiti’s slave populations early in the play. And much of what follows suggests that Toussaint understood the true meaning of Liberté, Egalité and Fraternité far better than Napoleon. In the graphic-novel version, comprising tight black-and-white line drawings (complete with caricatured, moustachioed Frenchmen and viciously scarified slaves), mosquitoes and the yellow fever they bring to the European colonisers become a recurring motif that further asserts the naturalness of Toussaint’s emancipatory cause. But while the illustrations are black and white, Toussaint’s story is not. Early on our hero is less than prominent. (‘They, the Negro slaves, are the most important characters in the play. Toussaint did not make the revolt. It was the revolt that made Toussaint,’ James is quoted as saying in the epigraph to this book.) Indeed, in the moments at which he does feature he comes across as a moderate and a pragmatist. Emancipation need not be absolute. Not every slave is ready for freedom. His loyalty to the king of France is not in question. As things progress, the king of France, the king of Spain (who will support the revolt against France and with whom Toussaint’s forces are briefly allied) and the king of Congo (as king of all Africans) come into play; then, two thirds of the way through, the king of England offers to make Toussaint a king too. As various powers try to shape Toussaint’s revolt, it turns out that the colonial world is one of constant temptation. And constant lies and misdirection. As he resists the temptations, Toussaint discovers that you can never be liberated by a third party; the only liberation is self-liberation. And without self-liberation, you can hardly liberate others. In one memorable, cell-free single page, depicting his moment of revelation, Toussaint is portrayed reading vehemently antislavery Enlightenment philosopher Guillaume Thomas Raynal’s Philosophical and Political History of the Two Indies, which was published in French in 1770. Those who support slavery, Raynal once said, should be ignored by philosophers and stabbed, with a dagger (rather than a theory), in the back. Nevertheless, while Toussaint grew happy to do the stabbing, his tale, as told here, is more about how he refined and purified his ideology and thinking around the subjects of race and freedom, to the point at which the revolution could be completed even after his death. The comic book format, constantly zooming out to the big picture and in on the details, proves immensely suited to the complex parallels between personal and universal struggles around which James’s play revolves.

Toussaint Louverture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History by C.L.R. James. Illustrated by Sakina Karimjee and Nic Watts. Verso, £11.99 (paperback)