Is paint the ideal medium for portraiture, or does it take words to convey something as abstract as the self?

The show that ran this winter at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, on Picasso and Gertrude Stein has kept me thinking, not so much for its overt attempt to link what the two of them were up to – because, really, is it possible to make so much of a friendship? – but more because it helped put pressure on the idea of the portrait, by which I mean the portrait as literature and as art. Picasso began his version of Stein’s portrait in a painting he started in 1905 and completed in 1906, having smeared out the original head and replaced it with a kind of archaic mask. And, wrote Stein in 1938 in one of her texts called Picasso, ‘I was and I still am satisfied with my portrait, for me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me which is always I, for me.’

But of course, immediately, in this delicate Steinian sentence with its multiple ‘I’ and ‘me’ and multiple tenses, we have a problem. It might seem that accuracy is what we want from a portrait, but in that case who is the judge of a portrait’s accuracy? And maybe more importantly, to what, exactly, is a portrait accurate – a self, a person, a person’s sense of their own self? And how might that change over time?

And also: if a portrait is trying to embody something as abstract as a self, then maybe the ideal portrait doesn’t exist in paint but in words? There’s a beautiful book edited by Emil Cioran, Anthology of the Portrait (1996), that offers up a series of paragraphs and pages mostly from the eighteenth century, in which writers tried to make portraits of their contemporaries. These portraits were often acidic and vicious, which is one of the book’s pleasures, but the other is that Cioran managed to find many moments of double focus – where a portrait by X of Y could be balanced by Y’s own portrait of X. In his introduction, Cioran pointed out that while a person making a portrait ‘could often be unfair, he could never be untrue’. That’s one philosophical truth of the portrait, but maybe his anthology itself reveals another: portraits are always a continuous practice of process.

It was shortly after Stein had her portrait painted by Picasso that she herself took over the apparently old-fashioned genre of the portrait in words. Instead of acidic description, she came up with patterns of repetition, like this text called ‘Picasso’ from 1909: ‘This one was one who was working. This one was one being one having something being coming out of him. This one was one going on having something come out of him. This one was one going on working. This one was one whom some were following. This one was one who was working.’ Stein herself wanted to believe that she and Picasso were doing the same thing: ‘Pablo is doing abstract portraits in painting. I am trying to do abstract portraits in my medium, words.’ But I’m not sure that abstraction is the right word for what she’s doing.

Another preoccupation in Stein’s longer text from 1938 about Picasso is an anxiety about the contemporary. She wants to be as contemporary as possible, and thinks that the most contemporary were Picasso in art and herself in literature. ‘One must never forget that the reality of the twentieth century is not the reality of the nineteenth century, not at all and Picasso was the only one in painting who felt it…’ And then: ‘I was alone at this time in understanding him, perhaps because I was expressing the same thing in literature…’

It’s partly just charming for its insistence on being as urgently modern as possible, but it’s also a hint that a self might be more bound up in processes of time and ageing than a single portrait could allow. Her writing practice in her own portraits was all improvisation and process, a kind of constant rhythm of insistences, of difference within iteration, so that a portrait wouldn’t set up anything so old-fashioned as a correspondence between a portrait and its subject, but more what she called a ‘word relation’. And this still seems contemporary to me, certainly more contemporary than a single painting.

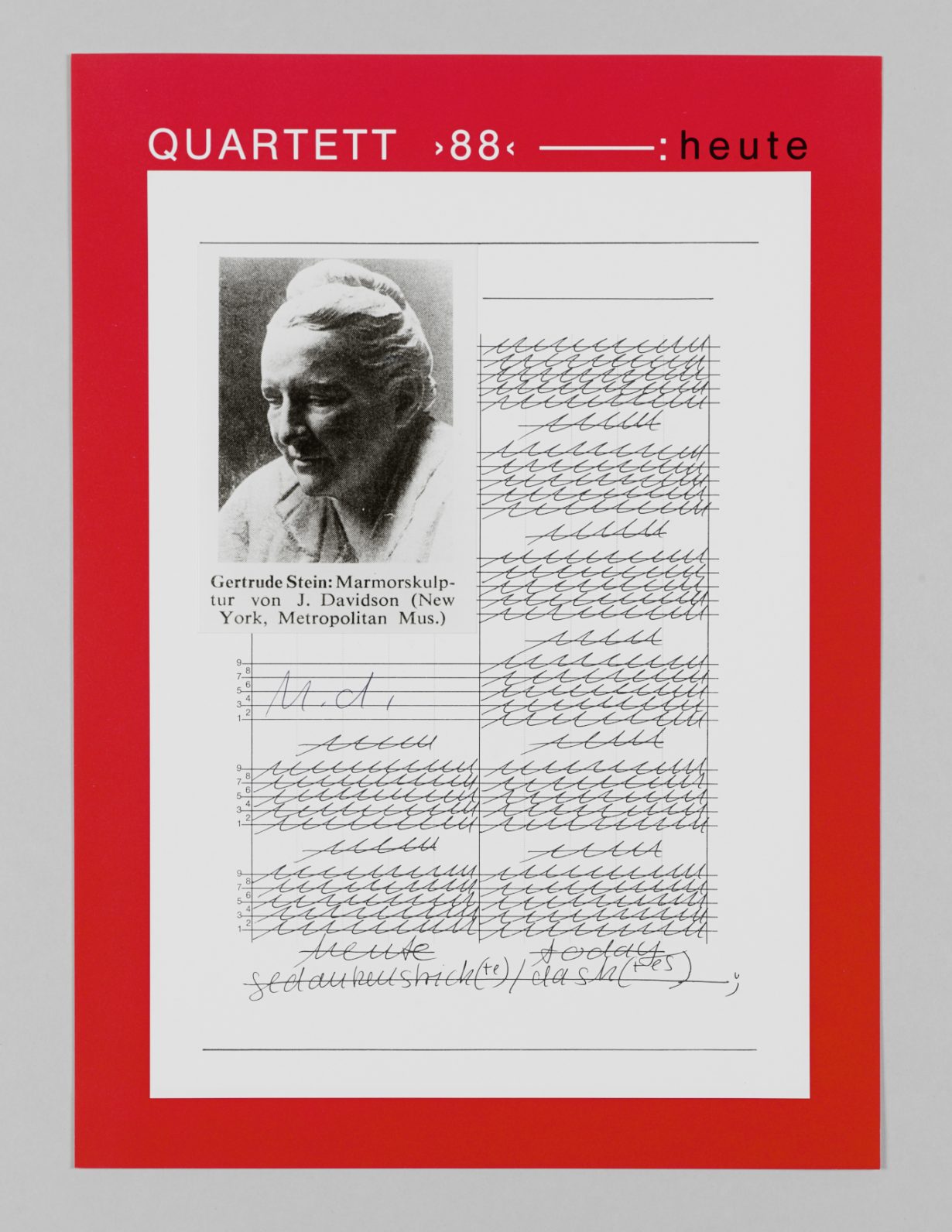

I think there’s an idea now that the human self has changed because of our many recent techniques of digital surveillance and self-display. It’s as if the truly contemporary self is both a surface and also a type. But I think that only describes one aspect of the equation. There’s something in Stein’s portraits that seems to imply that a portrait has to be a process, it has to include the passage of time, both of the self it might be describing and of the work that becomes a portrait; and it’s simultaneously a multiple process, where a portrait is as much a record of the act of looking as it is of being looked at, just as Cioran hinted in his existential/eighteenth-century anthology. In Composition as Explanation, published by The Woolfs’ Hogarth Press in 1926, Stein wrote: ‘The composition is the thing seen by every one living in the living they are doing, they are the composing of the composition that at the time they are living is the composition of the time in which they are living.’ It’s why one of my favourite other versions of Stein is the photo of a sculpture of Stein (made by Jo Davidson in 1920–22) that Hanne Darboven used in her Quartett >88< (1990) series – a photo pasted onto a diary page scribbled with a rhythmic organisation of words and abstract patterns. It’s a portrait, for sure, but not so much of either Stein or Darboven as of a continuous moment of living.

Adam Thirlwell is a novelist based in London