Revisiting Zarina’s subtle and quietly devastating artworks can be anchoring to anyone cast adrift by this abnormal life

© the artist’s estate. Courtesy the artist’s estate and Luhring Augustine, New York

A year and some months ago COVID-19 changed every accepted notion of the world. The fixed idea of ‘home’ that so many of us pursued was revealed to be a series of thin layers that seemed to collapse one upon the other, like a scene from the mind-bending movie Inception (2010). Home, if we still had one, became an all-encompassing site that housed office, studio, school, sometimes hospital, entertainment venue and much else.

For the peripatetic among us, home perhaps has only ever been an idea; the notion of it being either permanent or a physical site is just a vague, distant desire. It is a sentiment Zarina, the New York-based modern/minimalist/abstract artist of Indian origin who professionally went by only her first name, understood all too well. The artist, who spent nearly her whole career trying to navigate and reconcile with her search for the idea of home, passed away a year ago, in the spring of 2020. ‘Home’ was a theme she frequently explored in her woodcuts, sculptures, drawings that often used geometrical elements, and even in her writings, which were inspired by Urdu poetry. On a personal note, it has been nearly a year too since my partner and I moved from a city to a small town in the mountains of South India where I was born and raised (not driven out by the pandemic but influenced by it to advance plans that were already in motion). So for us, home is and, for the next few months, until our own house is built, will continue to be a contentious liminal space. But naturally, these two anniversaries have for me extended further to encompass all that happened this past year when the pandemic necessitated an overhaul of home, its meanings and associations for the self and those with whom we share that space.

Zarina’s was a generation that saw much internal displacement and migration after India’s Independence, in 1947. She mined the trajectory of her personal life to make her art, opening hers and her birth country’s traumatic history to global scrutiny. ‘I do not feel at home anywhere, but the idea of home follows me wherever I go,’ she once wrote.

Having spent her formative and university years (she studied mathematics) in Aligarh, a university town in northern India, she was thrown into a repeated cycle of homemaking in many cities of the world following her marriage to a diplomat. Even after the latter’s early death, and having set up studio in New York, she travelled the world in the name of her art. At the same time, the Partition of India, a cartographical exercise undertaken by the departing colonial power that broke land, history, families and the country into two, saw her family eventually move to Pakistan. By then, she had embarked on her travels too, and a rift opened up between the people and the land that she identified as home. A transient artist with access to multiple national identities before such terms were fashionable, Zarina identified as an exile.

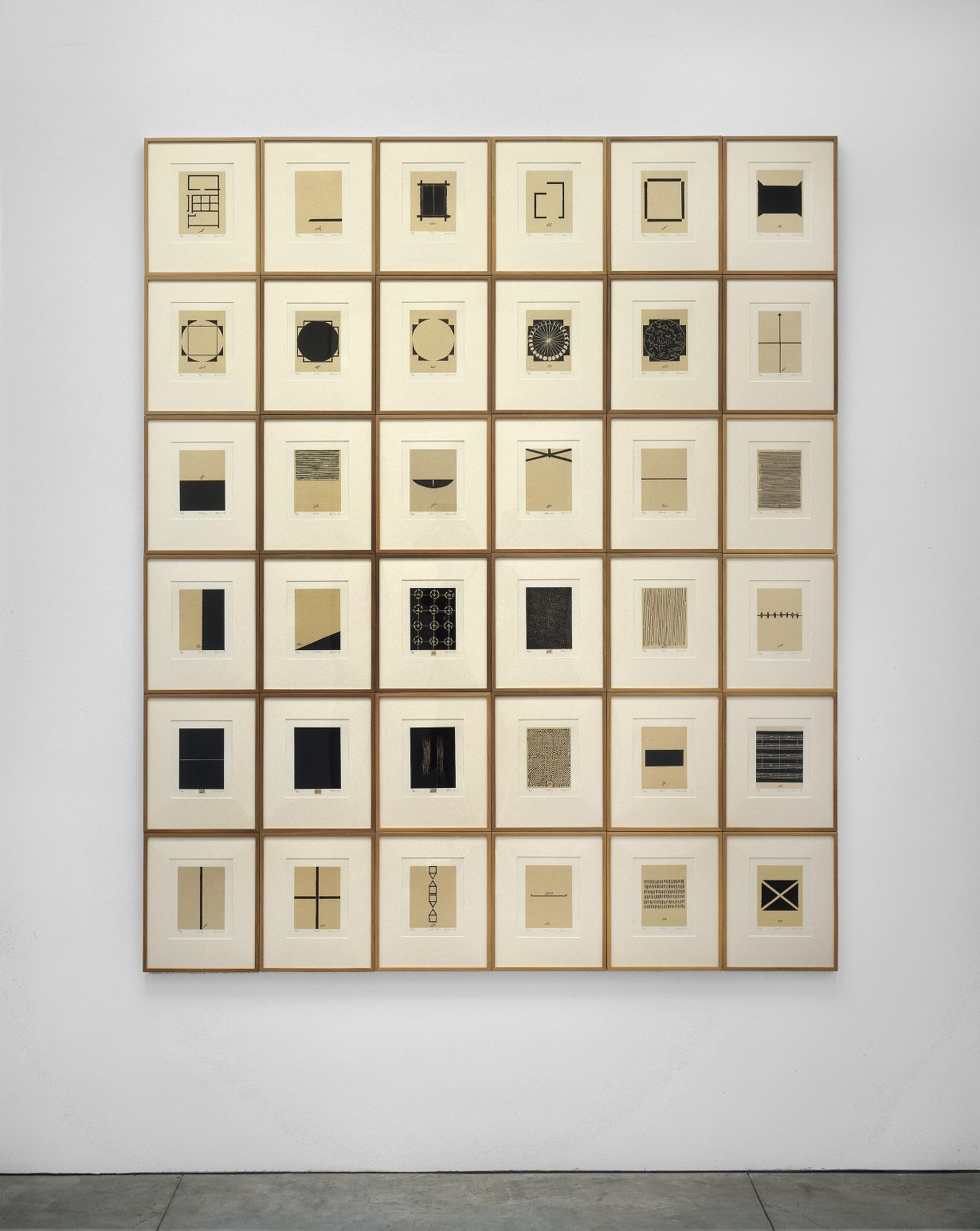

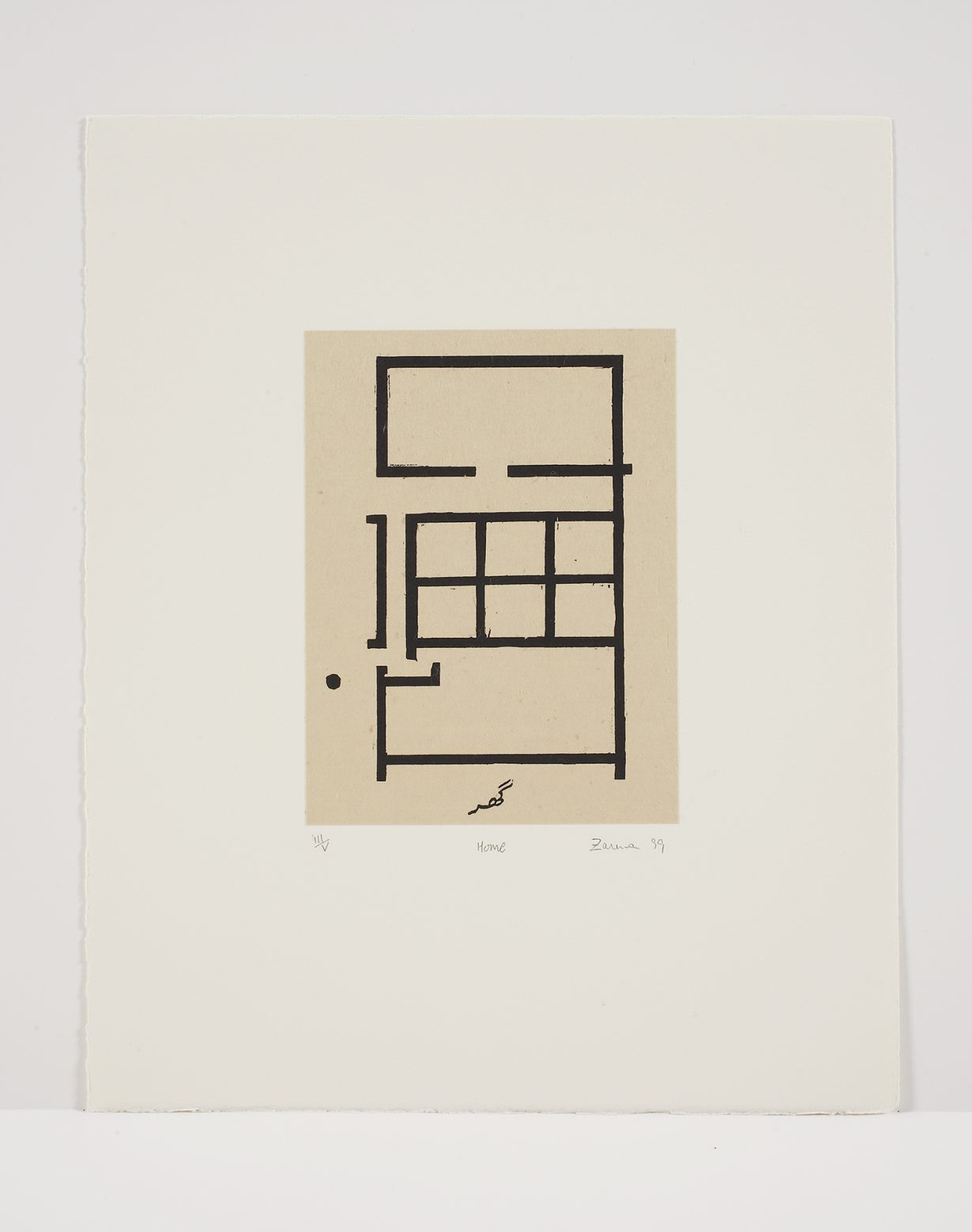

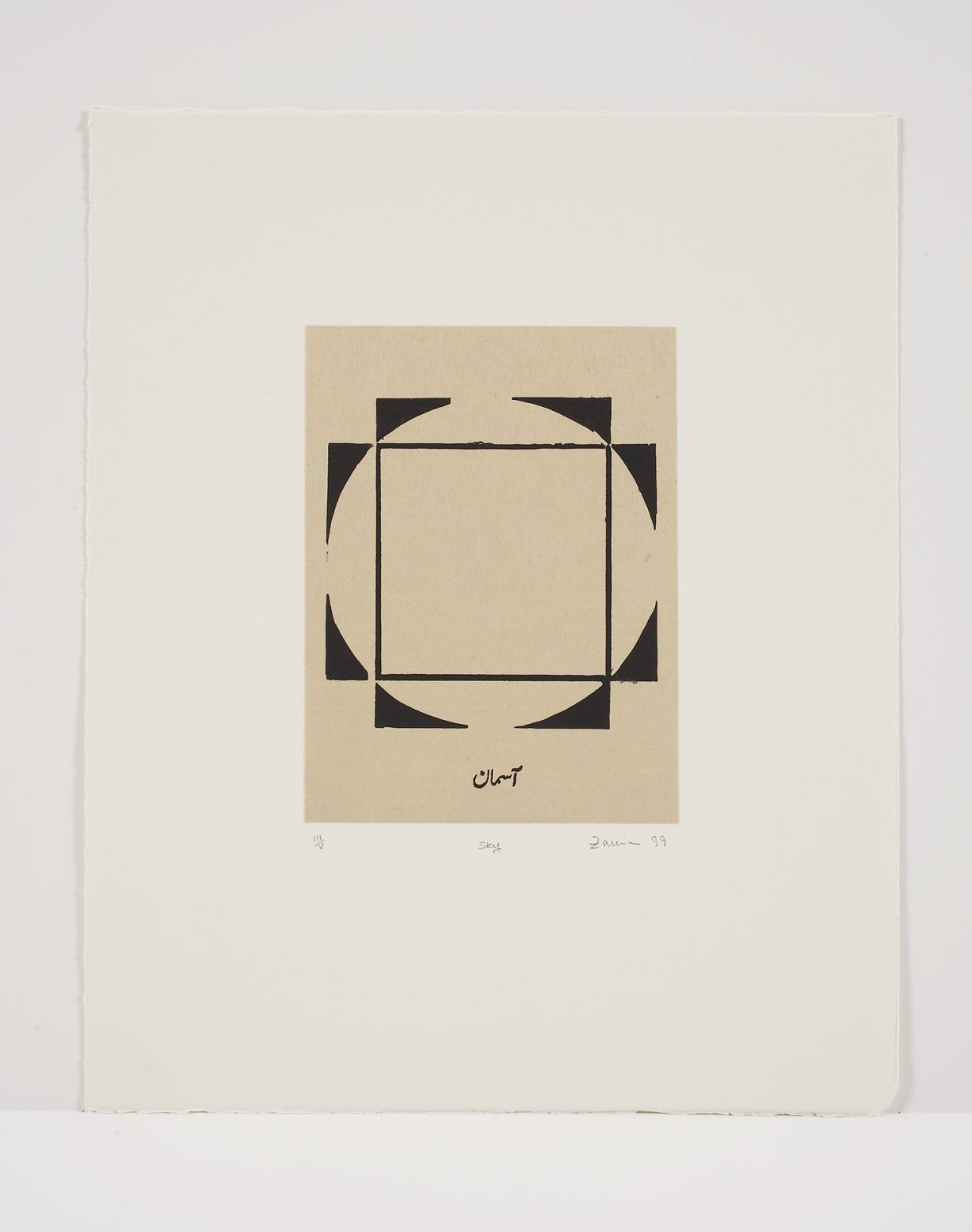

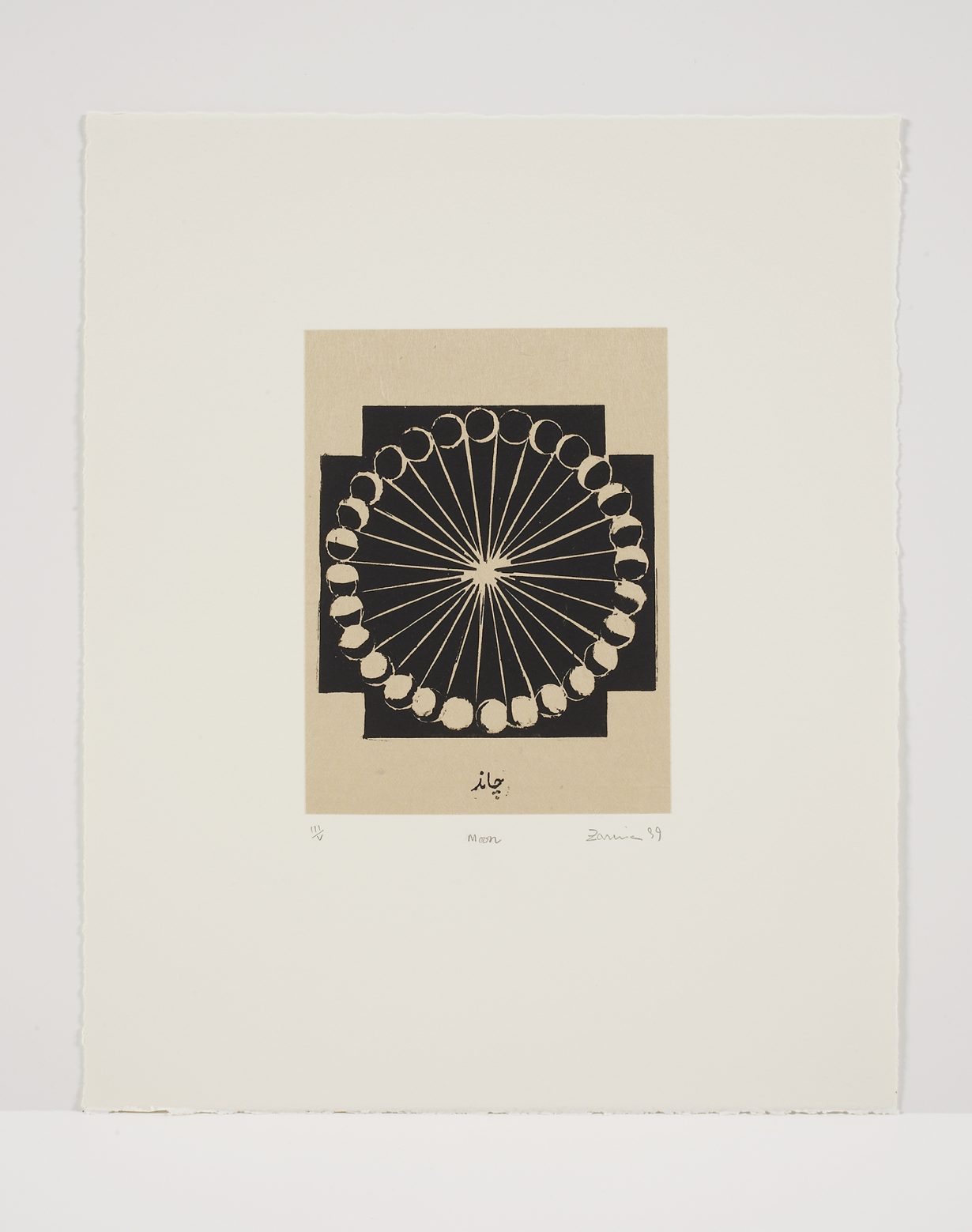

Her search for that one home with a capital H inspired her best-known works. Homes I Made, a Life in Nine Lines (1997) were architectural drawings of the various houses she lived in; Cities I Called Home (2010), woodcut prints of places her husband’s diplomatic career had taken them. While Letters from Home (2004) were prints of letters from her sister Rani, whose person Zarina identified as home, her birth town featured often in works, such as My Dark House at Aligarh (2017). Her celebrated Home is a Foreign Place (1999), an expansive exploration of various aspects of home through a combination of text and image,

a style to which she often returned, was made during a time she was facing eviction from her New York apartment. It is perhaps in the work Dividing Line (2001), though, referring to the Radcliffe Line that violently carved Pakistan from India, that Zarina most poignantly embodies that oft-repeated phrase ‘one can never go home again’.

Pushing the metaphors for home further, Zarina extensively used her mother tongue, Urdu – “My work is about writing,” she once said – with calligraphic and Islamic elements to tell her stories. Paper, a medium she famously likened to skin for its ability to age, stain and keep secrets, is fragile. Yet writings on paper retain a sense of intimacy and can last for centuries. These notions of impermanence, distances from people, geographical locations, her language and the resilience needed to accept the fragility of belonging were the layers in the idea of home she regularly sought. Home for her was a shifting entity, always just out of her grasp. While minimal in their execution, and thus open to multiple meanings, her works on paper and sculptures, mostly made with cast paper, are rich in associations.

One of the few women modern artists in the roster of celebrated Indian artists such as M. F. Husain, V. S. Gaitonde and Tyeb Mehta, Zarina might not have found a permanent ‘home’, but through her use of Indian paper as a frequent medium and motifs that resonated with American minimalism and elements of European modernism, she was able to bridge elements of the many continents in which she lived and made work.

One way to view Zarina’s works is to read them as the memoir she intended them to be – following a trajectory of early life in India, travels around the world, family strewn across the border in Pakistan, which wasn’t easily accessible, active participation in feminist movements in Europe and the US, and the involuntary wanderings of an exile who never felt at home anywhere. Her treatment of the idea of home is the story of global migration, events that can never be completely devoid of the trauma of leaving locations and people behind.

As of writing, most states in India are under various stages of lockdown, even as hundreds, and possibly many, many more, are dying for lack of medical oxygen and medicine. The wearing of double masks, even while home alone in larger cities, is being recommended. There is a vaccine apartheid thanks to the discriminatory policies of rich nations, corruption in the equitable distribution of doses among Indian states and the spectacular failure of the Modi-led government in managing the pandemic’s second wave. A third wave, perhaps a fourth too, are said to be imminent, and it is likely that stay-home will remain a directive for a long time to come. But revisiting Zarina’s subtle and quietly devastating works can be anchoring to anyone cast adrift by this abnormal life; indeed, they offer instruction in the ways in which the idea of home can encompass many overlapping and sometimes contradictory sensations – how homes can be sites of belonging, permanency, fragility, refuge, temporariness

and trauma, all at once.