At first sight, Chou Yu-Cheng’s artwork is like the quietest person at a party: it speaks slowly in a feeble voice and you don’t usually notice it immediately; it is invisible in a suspicious way. But when you look closer or open a conversation with it, you will find there are unexpectedly intriguing and fascinating things waiting for you. Chou’s work doesn’t surprise you with razzle-dazzle installations or beat the drums to call for dancing; rather, he designs minimal but deliberately orchestrated ‘tricks’ that hold a special attraction.

Chou positions himself as a pivot point, creating a centrifuge for the mechanisms and operation of a space. He intervenes in this system through language and techniques, suggesting an advanced improvement or modification. In the works TOA Lighting (2010) and Rainbow Paint (2011), he proposes to exchange the art object with the structural components of the institutional facilities that house it, challenging the economic system of patronage. Exhibition lighting equipment or wall paint of a specific colour derive status and meaning from the constant reproduction of their context and function; they become recontextualised through Chou’s play with the relation between source and product.

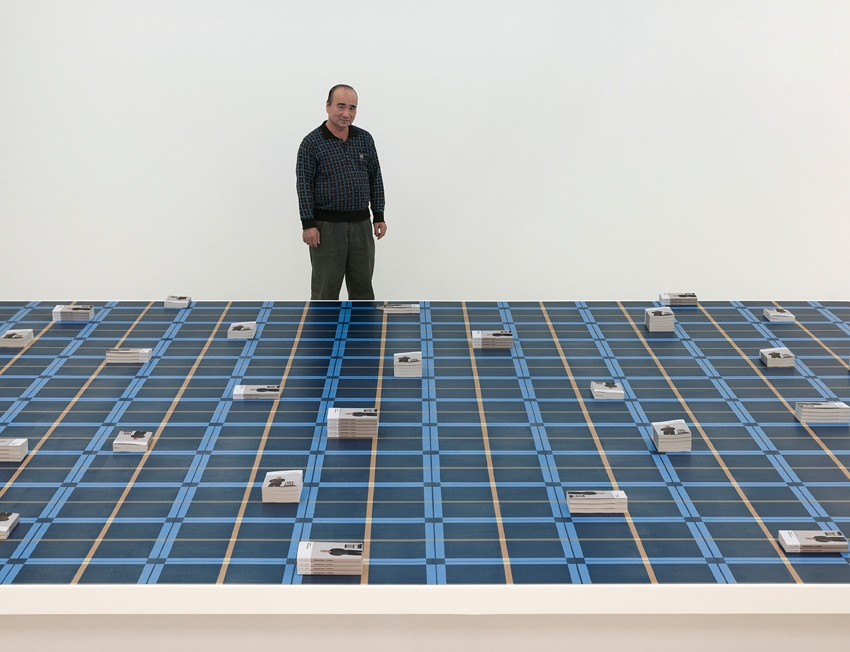

Chou seeks slits and unveils invisibility in the chain of events behind an exhibition. How is value produced? Who is engaging with the evaluation of value? These questions are further enhanced in his recent work, A Working History – Lu Chieh-te (2012). The work divides into two phases: at the first stage, Chou implemented the hidden economic realities of working conditions by employing a near sixty-year-old temp worker, Lu Chieh-te, and conducting interviews with him together with a ghostwriter. They wrote down Lu’s working history through the past 45 years and published the booklet as part of the final artwork. It is at this stage that A Working History won the Grand Prize at the Taipei Arts Awards, which made Lu an unexpected overnight superstar due to the massive media exposure. In the second phase of the work, Chou employed Lu as a security guard at the exhibition space. The physical presence of Lu guarding his own autobiography, added to his sudden fame, suggests implicit contradictions and uncertainties.

Chou uses strategies of ‘tricks of design’ to achieve subtle displacements of meaning, and questions and reflects the definition of what we see and conceive in particular milieus. In a sense it is the moment of ‘unexpected intrigue’ that produces a dialectical intervention.

Originally published in the Autumn & Winter 2014 issue of ArtReview Asia, in association with EFG International.