Much of the art of Lebanon’s influential post-Civil War generation – which includes artists such as Walid Raad, Akram Zaatari, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, and Rabih Mroué – relies on the status of the photographic image, playing its veracious claim as historical record against itself through strategies of fiction, absence, erasure and latency, to investigate the complex relationship between history and memory. Rayyane Tabet navigates similar terrain but adopts, instead, the approach of an archaeologist, excavating material rather than representational traces. These artefacts then serve as jumping-off points for subtle sculptural installations that attempt to transmute the recent past – personal and collective – into experiences of form, space, surface and weight.

Take The Shortest Distance Between Two Points (2013), Tabet’s debut exhibition at Beirut’s Sfeir-Semler Gallery, which traces the chequered history of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, a midcentury endeavour among three American oil companies to connect the oilfields of Dammam, Saudi Arabia, to the Mediterranean Sea over land. Tabet distilled more than half a decade of research into a precise sculptural meditation on the line as abstraction: folding rulers traced the pipeline’s path to scale on one wall; 40 steel rings created a line down the centre of the gallery; pages of frayed yellowed stationery, recovered from the company’s abandoned Beirut headquarters, were presented, framed, in a neat row on another wall. Ultimately, every line is just a set of points, and the tension between the line’s unrelenting continuity and the integrity of each point along its path serves as a poignant metaphor for the difficulties of excavating and representing history.

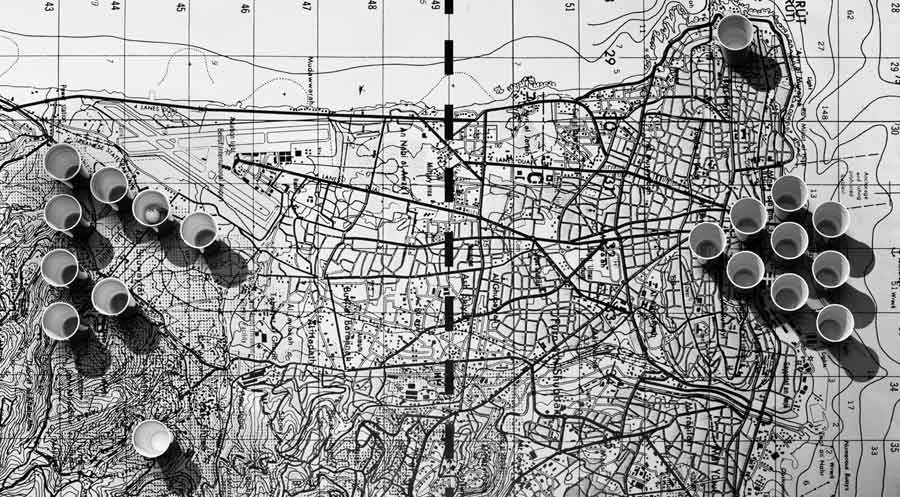

In other projects Tabet uses popular games and rituals to help lighten the load of history. Inspired by an American college drinking game named after his hometown, How to Play Beirut (2009) riffs on the double meaning of being ‘bombed’. Tabet produced a table customised for the game, the holes cut out to hold beer glasses introducing craterlike scars into the city map grafted onto its surface. And for Fire/Cast/Draw (2013), Tabet adapted a ritual to ward off evil performed by his superstitious grandmother into an artistic act: a handful of lead shot, each the weight of a bullet, was cast and cooled in water into a unique nugget, whose craggy surfaces are supposed to reveal your enemy’s face, thus neutralising his power. Tabet repeated this 5,000 times, extending its promise of protection to the collective, materialising, through art and superstition, the missing evidence needed to bring to justice those culpable for the region’s many conflicts and failures.

Originally published in the March 2014 FutureGreats issue, in association with EFG International