Selected by Rashid Rana

At first glance, to predict the increased popularity of an artist’s practice belies a belief in the linear progression of time. As if fame and recognition lie quietly in wait at the end of a proverbial tunnel. I am proposing however, that notions of visibility and temporality are not as simplistic, particularly in Pakistan, where multiple chronologies coexist simultaneously. Therefore, the artist I am choosing to shed light on is Zahoor ul Akhlaq, born 1941, died 1999, the trajectory of whose career is already in front of us. Akhlaq was my teacher at Lahore’s National College of Arts and his mentorship and practice has singularly influenced a greater number of artists from Pakistan than any other figure.

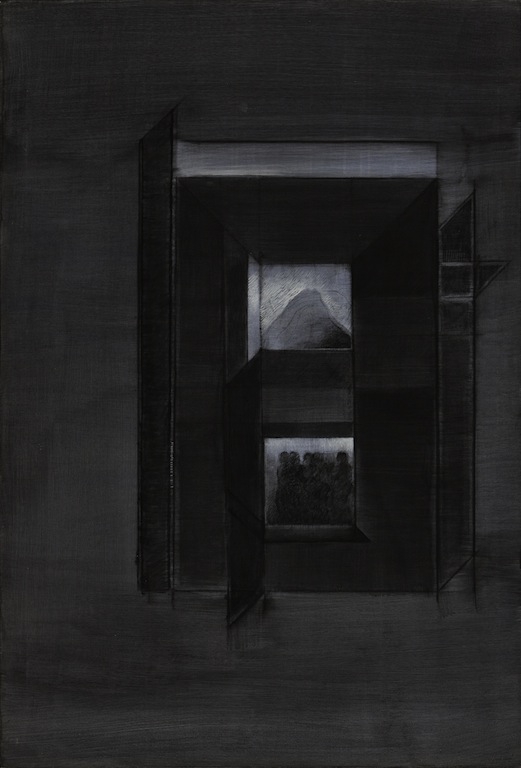

Artists are often occupied with a negotiation between the actual and the remote. The former is something close at hand that can be experienced directly, while the latter is composed of indirect sources of knowledge that may be scattered across space and time. Akhlaq’s peculiar synthesis of the actual and the remote is manifested in his critical take on ideas of tradition as well as the notion of a universal present moment: he engages with both the past and the present beyond the limited scope of geographical borders but remains unsubscriptive to either. This is all the more significant if we examine the context of the time in which he practiced where the ‘East’ and ‘West’ dichotomy was more entrenched. Yet, Akhlaq was able to overturn expectations and lay open claim to influences as diverse as Minimalism and traditional Indian and Persian manuscript painting. In retrospect, I believe that Akhlaq’s work set a precedent that provided frameworks to many contemporary artists, for shaping questions of identity and its relationship to physical and chronological location.

Akhlaq’s work has been typically pigeonholed as late modernist, which is an erroneous and ethnocentric category that presupposes a causal relationship between a European and North Atlantic modernity and the particular inquiries of other regions. In my view the term ‘modern’ is misleading in the context of regions such as South Asia, which haven’t undergone ‘modernity’ in the sense it was imagined, understood and practiced in the West. Thus works by artists from South Asia in that era were often unfairly regarded as derivative. However, while the modernist period was one of obsession with originality in the West, it was an age of concurrent acts of assimilation and rejection in post-colonial, non-western regions. It is important also to note that a posthumous contextualising of Akhlaq’s work is happening in light of the increased popularity of contemporary practices from the region, and is expected to generate fresh readings that will establish Zahoor ul Akhlaq’s legacy both there and beyond.

Zahoor ul Akhlaq was born in Delhi in 1941. He studied at the National College of Arts in Lahore (NCA), graduating in 1962, before attending the Hornsey College of Art and the Royal College of Art in London, and then Yale University, New Haven. He taught at Bilking University, Ankara, and served as a professor at the NCA for over 25 years. He died in 1999.

This article was first published in the January & February 2016 issue of ArtReview.