For some time, the so-called editors of this magazine have been badgering me to write something about actual curating on these pages: “Everyone wants to do it, so you should tell everyone how!” they keep belching at me, chasing bits of crispy pork round a plastic bowl while using two hands to make stabbing motions with bamboo chopsticks from the takeaway next door. Who do they think I am? Hans Ulrich Obrist or something?

Who do they think I am? Hans Ulrich Obrist or something?

As it happens, though, I’m currently working on a major exhibition. Partly inspired by a summer spent touring Venice, Kassel, Athens, Stromboli and Hydra (hey – first expert tip: be present at everything). It’s called The Potato-Print Biennial and it’s by the art people for the actual people and in a medium to which the latter can really relate. I’m inviting a series of international artists to produce images exclusively created using the artworld’s preeminent vegetable-printing method: a working-class medium that requires artists to do some actual work. It’s important always to remind people that artworking is real working. And that curating is all about keeping things real. In fact, all-in-all, things are more equitable this way – everyone using the same medium, no one hogging attention with their hourlong video installations. Democracy is a big thing these days. It’s made America great again.

And I’m going to get it all sponsored by Tayto crisps (or ‘chips’, as our illiterate American cousins know them). Here’s their story: ‘Set deep in the heart of the Ulster countryside in Tandragee is Tayto Castle where Tayto crisps and snacks have been made for the past 60 years.’ It’s important that everything in your show has a story. Everything. You can’t rely on punters and critics to think for themselves. They’re not used to it any more. Of course, it’ll be good to get some potato-famine references in too. I learned at Documenta that it’s important to get in a few references to colonial atrocities and oppression into a show. People take you more seriously if you do. And an economic crisis. I learnt that from Athens – when it comes to being the centre of art, they’ve never had it so good. Well, not since the fifth century BCE, which is so long ago it doesn’t really count in the contemporary art game. In any case, the point is that art = economic prosperity. That’s why there are so many biennials.

You can’t rely on punters and critics to think for themselves

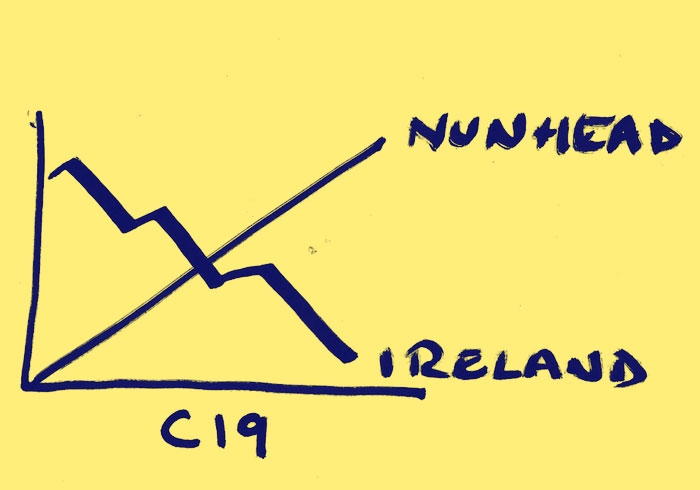

But I digress. You want concrete tips. The centrepiece of the show will be a lifesize reconstruction of Belfast Castle made entirely out of blighted Irish potatoes (you see, I can allow the sponsors to refer to it as Tayto Castle – that’s how you lock down a sponsorship): the potatoes that got censored. I’m going to stick it in the faces of the colonial masters by erecting it in the Victorian-era suburb of Nunhead, so that the bastards can come face-to-face with the price of their insatiable consumerism and historic exploitation. As London expanded, Ireland declined: those guys from Mousse (NB: very curator-friendly, unlike the brutes who run this organ) will be running a potato-print press to reproduce historic records (designed by Maria Eichhorn, of course) documenting how the rise of one was built on the fall of the other. It’s important that an exhibition be a literal site of production: people don’t believe in things they can’t see. That’s why witchcraft isn’t as popular as it once was.

By now the observant among you will have begun to notice that there is a bit of an international flavour to my exhibition. You’re right! I’m going to move the Nunhead Art Trail on from its pathetic insularity and make it truly global! Like Tate Modern did to Tate Britain. Welcome to Tayto Modern; you may refer to me as Sir Ivan!

people don’t believe in things they can’t see. That’s why witchcraft isn’t as popular as it once was

But enough about me. The ‘editors’ tell me that you people are always bothering them with questions about how to commission art. It’s tricky. Because artists don’t understand the point of a commission: they never really manage to stick to what you tell them to do; they always want to have ideas of their own. I know! They think they’re the curators! But in Nunhead I’m in charge. I can’t tell you much about my plans, though, because like all biennials, peace negotiations, Brexits and day-to-day White House operations, secrecy is paramount. Curators are not for leaking. Just because you’re ArtReview readers, however, I can reveal – exclusively (yes, you can put that word on your cover once you’ve finally caught the pork, Mr Editor) – the details of two other non-print-related commissions (as Walt Disney used to say, you always need to dangle a wiener in front of your hungry punters). I’m going to be commissioning Ibrahim Mahama to cover Nunhead Cemetery Chapel in jute sacking that was formerly used to transport Irish potatoes. In case it’s not obvious, that will highlight the redundancies in capitalist transactions, take Mahama’s concept to an international level and allow him a subtle wink at his recent legal issues with Irish gallerists (thus invoking art’s all-to-cosy relationship with commerce) and me a tip of the cap to the genius of Adam’s Documenta. The biennial will conclude with a relational performance by Rirkrit Tiravanija in which he serves people the used potatoes (the ones used to make the prints) reformulated (and recycled – never forget ecology and environmentalism) into a traditional Tom Yang Koong (he’ll be using the kitchens of Chai’s Garden, Nunhead’s finest Thai eatery – taking art out of the white cube and into people’s faces, literally). It’s important that he’ll be using none of the traditional ingredients, though, in order to create a commentary about the losses and profits of globalisation. And, of course, it’s a nod to that celebrated Irish staple: potato soup. For those of you who care (and remember, curators always do), Rirkrit will be using the recipe from irishamericanmom.com (‘I’m Irish. I’m American. I’m Irish American. Welcome to my melting pot’). It’s important to see your themes through right to the bitter end.