In Southeast Asia the antiquities trade is under closer scrutiny than ever before, but if the region is to keep hold of and preserve its heritage, there’s a long way further to go

During the early 1920s, the American poet and playwright Arthur Davison Ficke did some opportunistic plundering at the ruins of Angkor Wat. There, while rambling around the ‘finely proportioned and lofty pyramidal temple’ of Takeo, he had come across two dark, basalt sculptures: one of the Hindu deity Shiva ‘standing in a lordly attitude of repose’, the other his ‘delicately but powerfully moulded’ wife Parvati. Astounded at their beauty, he was suddenly overcome with a mixture of awe and acquisitiveness. Before he knew it, Parvati’s loose head – ‘severe and magnificent, noble and sensual, disdainful and exquisite’ – was in his possession. A sleepless night ensued. ‘My triumph, and the desire to look incessantly at that beautiful cold proud face, kept me awake,’ he wrote in his 1921 account for The North American Review. ‘For me, the might and majesty of Angkor was all concentrated in that head.’ Mostly, though, he felt vile for having committed ‘a terrible and irreparable injury’ to a sublime work of art, analogous in his mind with ‘the Winged Victory which now stands headless at the top of the great stairway of the Louvre’. Come dawn, Parvati was whole again.

Ficke’s self-aggrandising anecdote puts a happy spin on a depressing trope: while many foreign admirers have purloined the stone, bronze or gold treasures of the Khmer empire, whose divine kings ruled over parts of modern-day Cambodia and Thailand between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, few have handed them back so quickly or enthusiastically. Two years later, an intrepid young André Malraux, the French author who went on to become a national icon and minister of cultural affairs, made it as far as the capital Phnom Penh before being caught with his ox-drawn caravan of booty: around 650kg of sculptures and bas-reliefs hacked from the Banteay Srei complex. A trial in Phnom Penh followed, but there was no prison sentence and never any contrition on Malraux’s part.

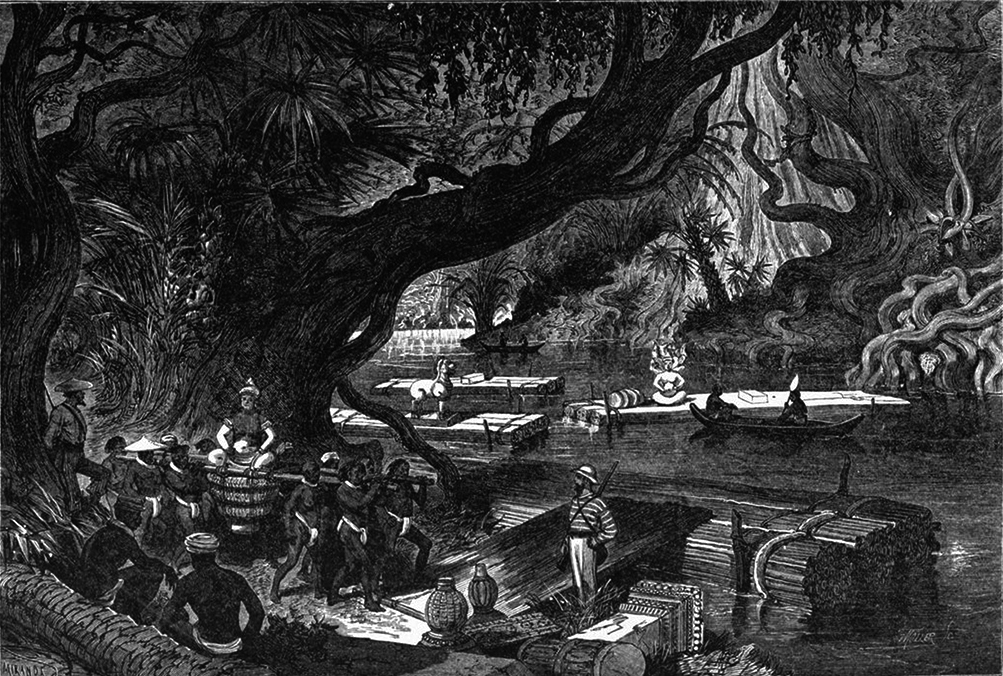

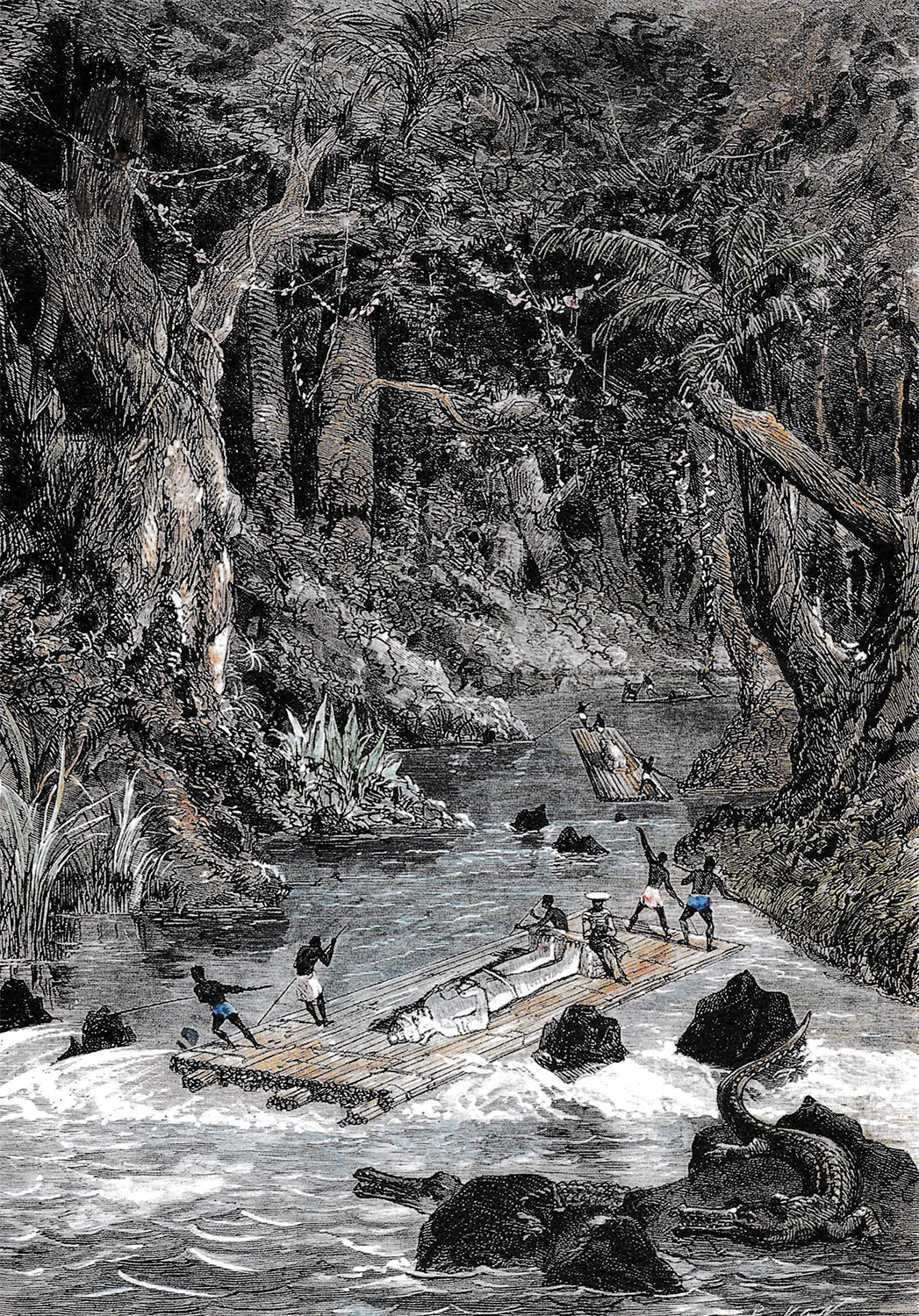

In Angkor’s Temples in the Modern Era: War, Pride and Tourist Dollars (2021), John Burgess describes how pilfering was such an issue under French colonial rule, which ended in 1953, that signs beseeching visitors not to destroy or remove objects were erected; major sculptures were moved to depots for safe keeping; and, to disincentivise theft, genuine items deemed of no archaeological interest were put up for sale. And this is to say nothing of the ancient antiquities removed by their self-appointed custodians. Under the banner of patrimoine, or cultural heritage, many sculptures were hauled out of the jungle using rope pulleys and lowered onto rafts for transport to the museums of France, where they remain to this day. Others were sold to foreign institutions in high-priced sales, or exchanged in return for museum-quality objects from other countries.

But while such cases hail from a time when Western imperial powers and their citizenry didn’t know better (or so the fading excuse goes), any last traces of Old World romanticism and derring-do have been dispelled by the Douglas Latchford case. Born in Bombay to English parents, this self-styled ‘adventurer scholar’ – who died in Bangkok, aged eighty-eight, in August 2020 – was, in recent years, accused of being the conduit in a major antiquities looting and smuggling network that flowed from Cambodia’s sylvan Khmer temples through rural Thailand and Bangkok, then on through the moneyed capillaries of the artworld. He is said to have done this as civil wars, rebel groups and genocidal Khmer Rouge-rule ravaged the country – and to have thrived on this conflict, not in spite of it.

In the eyes of his critics, a veil of respectability and a veneer of scholarship allowed him to operate in plain sight. A successful businessman and bodybuilding impresario who made his fortune in pharmaceuticals and property, he had dual Thai-British citizenship and friends in high places. In Cambodia, he donated money and the occasional item to the national museum, and even accepted an award for his ‘unique contribution to scholarship and understanding of Khmer culture’. He also self-published three quasi-academic books, among them 2004’s Adoration and Glory, a lavish compendium of Khmer stone treasures ‘dedicated to the Khmer people’. Containing sumptuous images, essays and admiring testimonials from Cambodia’s culture and museum ministries, its high production values now stand accused of masking a calculated goal: to launder anonymous private collections (his, we can assume) of suspect origins. With many of the beguiling stone figures shorn of arms, legs or heads, it is also a glossy catalogue of the horrors meted out by looters.

In the last decade of Latchford’s life, a few events caused the facade to crack. In 2012 a tenth-century Duryodhana statue broken at the ankles went up for auction at Sotheby’s, only to be withdrawn at Cambodia’s last-minute request. The subsequent legal case brought by the US government, which alleged it had been looted in 1972 from the Prasat Chen temple at Koh Ker – a remote tenth-century complex once studded with statuary – and then sold on by a Bangkok-based collector who knew it was stolen, led to its return in 2014. Four other fine Khmer statues also suspected to have flowed through Latchford’s network, among them Bhima – a tenth-century sculpture featured in Adoration and Glory and identified as the twin of the Sotheby’s statue – were likewise repatriated to Cambodia in the same timeframe by the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and a private collector. More restitutions followed. In effect, the game was up: a coterie of lawyers and researchers had begun to expose the litany of half-baked provenances and subterfuge that served Latchford and his transnational network of collaborators so well for so long. Upon his death, with a 2019 indictment by US authorities still unresolved, his daughter appeared to concede as much when she voluntarily gifted his entire collection – over 100 pieces of Khmer sculpture, architecture, gold and bronze – to the Cambodian people. ‘The collection simply became a burden to me,’ she told The Art Newspaper this year.

But while the artworld turned against Latchford, it barely humbled him. In a 2008 interview with Apollo magazine, he ushered a journalist into his softly lit London Mayfair apartment, where he proceeded to show off his fastidiously accumulated assortment of fullsize Khmer deities lined up against the walls, some drenched in gold jewellery. ‘The collection is not overwhelming in size but the museum in Phnom Penh agrees that the pieces are the best of their type,’ he said. By 2014, however, he cut a more cagey, reticent figure. In The Stolen Warriors, Wolfgang Luck’s 2014 documentary about the Sotheby’s case, he agreed to speak on camera, only with one precondition: do not film the righthand side of his Bangkok apartment – the side groaning with Khmer treasures. He then denied ever owning the Duryodhana statue or being part of a smuggling network: ‘Their imagination has gone wild… They’ve seen too many Indiana Jones movies’. He also alluded to a secret video that proved his innocence. “However,” intimates the narrator, “he cannot allow it to be shown on TV. If he did, he says it would incriminate one of the leading Thai families as big-time smugglers. We have no way of verifying his claims.”

While on the back foot in his twilight years, Latchford appeared unassailable in Thailand – the country in which he had lived for over 60 years and that accommodated him and his collecting habits. It was in late-1960s Thailand that he began scouring Bangkok’s now defunct ‘Thieves Market’ for the Khmer antiques trickling in from Cambodia. It was in Thailand that he acquired his knowledge of Khmer antiquities, by travelling, along bumpy roads through the dry landscapes of the northeast, to see and touch the eleventh- and twelfth-century Khmer temple-city ruins of Phnom Rung, Muang Tam and Phimai. ‘It was an open-air encyclopedia,’ he told Apollo. Such recollections may seem innocuous, but of these trips over half a century ago, he also boasted casually of hunting down offsite sculptures. ‘I would show local governors a picture of a sculpture and ask them if they’d seen anything like it,’ he recalled. One that he claims to have somehow ‘bought’ from a field in Thailand’s Surin province and brought to Bangkok was, he added nonchalantly, acquired by John D. Rockefeller and eventually ended up in the Asia Society in New York.

An even more audacious Khmer statue trafficking ring – one with Thailand as the laundering transit point – was later exposed in the field research of Simon Mackenzie and Tess Davis. While Latchford is not named in their two studies from 2014–15, their investigations in Cambodia and Thailand uncovered a ‘trafficking channel that was essentially fixed for several decades, in terms of its roles, the occupants of those roles and their trading relationships’. It comprised two networks: one running through northwest Cambodia and directed by local gangsters; the other through the north of the country, run by members of the Khmer Rouge.

Thought to have originated in around 1970, shortly after the start of Cambodia’s civil war, both channels are said to have funnelled looted statues via oxcart, truck and even elephant into Eastern Thailand. Receiving them in Bangkok was a Janus-like figure with ‘one face looking into the illicit past of an artefact and one looking into its public future where that dark past is concealed’, write Mackenzie and Davis. No mere middleman, he or she performed a sanitising role while also being the broker-cum-ringmaster and, therefore, ‘the real looter’. Delving into the lucrative Bangkok-centred trade in Khmer art, both fakes and originals, the reports also implicated the customs authorities, whom they say had ‘no appetite’ for restricting the export of any country’s cultural heritage ‘other than their own Buddhist pieces’.

If true, this is no small scandal, especially as those exposing it have hinted at menacing undercurrents. Writing in The Diplomat in August 2020, Davis, executive director at The Antiquities Coalition, in Washington, DC, stated: ‘While investigating his [Latchford’s] network, I was told more than once to drop my inquiries. A Bangkok journalist, whom I tried to interest in the story, flatly refused, citing Latchford’s connections to the Thai military and the going assassination rate.’ But the big story here, bigger even perhaps than the full magnitude of Latchford’s crimes, or the grubby question of who sold what, to whom and when, is where the remaining Khmer treasures are, and what is being done to prevent more such losses.

As the latest return – a sculpture of Hindu deity Skanda riding a peacock, voluntarily forfeited to US federal authorities by an unnamed owner in July – shows, unravelling Latchford’s ties with international dealers, auction houses, private collectors, galleries and museums is key. But again, the Thailand connection is also germane: just as Cambodia is welcoming home Latchford’s plunder, the country in which it ended up or transited is pushing for the return of its own lost antiquities, some of Khmer origin. In tandem, the Thai government, which has had a bilateral agreement with Cambodia concerning the trafficking and restitution of cultural property since 2000, has announced a belated plan to ratify the relevant international conventions.

On a recent weekday morning, I went to see a temporary exhibition of two hand-carved sandstone lintels that disappeared in mysterious circumstances from two of Thailand’s Khmer temples, Buriram province’s Prasat Nong Hong and Sa Kaeo province’s Prasat Khao Lon, back in the 1960s, but were recently handed back by the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. Mounted on raised pedestals, these rough-hewn eleventh-century architectural relics – one known to have been among the 7,700 Asian artworks and antiquities donated, starting in 1959, to the Asian Art Museum by Chicago industrialist Avery Brundage, the other purchased by it in 1968 from a Paris dealer – are the current centrepieces at the Issara Winitchai Throne Hall, a richly decorated building originally used as a royal audience chamber but now forming part of Bangkok’s National Museum complex.

On display through September, their curlicued leaf motifs and weatherworn Hindu deities – Yama riding a buffalo, Indra kneeling above a Kala face – appear out of place amid the gilded Rattanakosin-dynasty artistry and immaculately staged Theravada Buddhist symbology of the hall. But while slightly jarring, this display is a stark reminder of how the story of the Khmer empire has been absorbed into Thai, as well as Cambodian, history. For much of the twentieth century, the two countries were locked in disputes over land and the Khmer ruins that stand on it, as borders established by the French were contested. Throughout the key defining events – Siam’s 1907 return to Cambodia of the province containing Angkor Wat (renamed Siem Reap, or ‘Defeat of Siam’), Angkor’s meteoric rise as a tourist destination, Cambodia’s 1962 international court victory against the Thais over the border-straddling Preah Vihear temple – those Khmer temple ruins still on Thai soil (referred to typically as ‘Lopburi’ or ‘Lopburi-style’, in reference to the ancient city of the same name) have steadily grown in religiopolitical significance. And not without some justification: a thread of Khmer influence winds through Thailand’s national story.

Still, a striking divergence in nationalist rhetoric is clear. For many Cambodians, such returns expose raw, stinging wounds as well as feelings of cultural pride. As the country’s minister of culture and fi ne arts, Phoeurng Sackona, told The New York Times upon hearing of the Latchford donation: ‘These are not just rocks and mud and metal. They are the very blood and sweat and earth of our very nation that was torn away.’ In contrast, the return of two ‘Lopburi’ lintels to Thailand was, while also an international news story, framed in less emotive terms as a legal and moral victory.

Which is not to say that the Thai authorities take these matters lightly. During the sacred ceremonial fanfare accompanying their late-May arrival, Tanongsak Hanwong, an archaeologist on the government committee responsible for retrieving looted art from abroad, said the case ‘sets an excellent example for the museums that still own Thai artifacts illegally, because they know they will lose the case’. He also claimed many museums had already reached out ‘to begin the return process instead of going through the legal process’. According to Prateep Phengtako, director general of the Thai Culture Ministry’s Fine Arts Department, a total of 32 such requests are underway in America, and similar cases in other territories are set to follow. “After these cases we will do the same in other countries in Europe, such as England, Sweden, France and the Netherlands,” he told ArtReview. As of today, the wish list includes Dvaravati-era Buddha images and ornate Khmer architectural elements such as lintels, pediments and pillars. Although unconfirmed, future requests are likely to include several highly prized bronze Bodhisattva statues from Prasat Hin Khao Plai Bat II, a tenth-century Khmer brick temple in Buriram province (The Met and the Norton Simon Museum are among the museums in possession of the latter).

The extent of Latchford’s involvement in these cases, if he is involved at all, is unknown (although my hunch is that the chances are high: on the British Museum website, for example, a ‘DAJ Latchford’ is listed as having donated two Khmer-era lintels and three Dvaravati boundary stones, all of Thai origin, between 1970 and 1975). What is clear, however, is that the Thai authorities want to keep a tighter lid on the export of all antiques and religious artefacts going forwards. The exhibition at the National Museum proudly chronicles the many steps – the years of rallying and negotiation in close collaboration with the US government’s Homeland Security Investigations team – that led to the repatriation of the lintels (for its part, the Asian Art Museum claims that it had already planned to return them, prior to receiving a US Department of Justice civil complaint last October). But after admitting that this complex bilateral process was ‘tedious and resource intensive’, National Museum also says it must be avoided in the future through better prevention. ‘This would not be too hard,’ the exhibition text states, ‘if all Thais are deeply conscious of their long and precious heritage and fiercely protect these artifacts so that they can be handed down to later generations.’

While this might sound like hot air pandering to nationalist sensibilities, there is a more substantial development that may prove, if followed through with, more effective – not only in preventing future losses of significant Thai antiquities, but also in helping Thailand to cast off its longstanding reputation as the primary, legitimising conduit for the smuggling of Cambodian sculpture and stonework. To date, Thailand has not ratified the 1970 UNESCO convention on illicit trafficking, nor its complementary follow-up, the 1995 UNIDROIT convention. Together these two legislative instruments (while not retroactive and therefore not applicable to the colonial era) provide the 141 signatories with a range of mechanisms of cooperation for preventing the illegal trafficking of cultural property, or for making swift claims for its return when it does happen. These mechanisms are more streamlined than the bilateral agreements countries fall back on when they haven’t signed.

According to Etienne Clément, an international lawyer and former UNESCO official, this is not the first time Thailand has announced its intention to ratify the two conventions. However, the formal manner in which Thailand’s minister of culture, Itthiphol Kunplome, announced the latest plan on 29 June – during an online UNESCO Bangkok event marking the 1970 convention’s 50th anniversary – suggests that the means and momentum are finally there. “To do it in the opening speech of a conference is very significant,” said Clément.

Thailand, it should be stressed, is not the only holdout in the region: across Southeast Asia (as well as the Pacific), the ratification rate is among the lowest in the world – a fact many observers find strange given the many manifest threats to its rich cultural heritage. Source countries without strong international art markets, such as Cambodia and Myanmar, were onboard early. But many destination countries in the region have held off, either because they deem the convention low priority, or not of national interest, or too ‘statist’. Others, among them Thailand, have taken a more finicky, legalistic route – claiming that they can’t ratify until they’ve first tweaked their domestic laws and legislation. According to Clément, the situation now in Southeast Asia is similar to that in Western Europe during the 1990s, where it took heavy lobbying before destination countries like UK, France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland signed up. In his opinion, it is also illogical. “These instruments are considered almost universal now, and very benign and balanced,” Clément explained. “If you look, a bona fide purchaser in a country of destination can even get compensation. It’s not a convention that goes all in the direction of the interests of the source country.”

But conventions are only one part of this transnational jigsaw puzzle – effective implementation of national policy is also key. Thailand, for example, has had an act controlling the export of antiques since 1926, during the reign of King Rama VII. However, neither it, or the Act on Ancient Monuments, Antiques, Objects of Art and National Museums that replaced it in 1961, or its 1992 amendment, were successful at stemming the steady bleed of looted antiquities out of the country.

Reversing this bleed, across the region as well as in Thailand, won’t be easy. According to Davis, it is more simple than ever to hawk stolen antiquities thanks to technological advances, such as global express shipping, instantaneous money transfers and social media, and ‘Asia and the Pacific are under particular attack’. New research by UNESCO, for example, has shown that online platforms such as Etsy and eBay are fostering a new generation of reckless collectors of Southeast Asian artefacts. On these sites, awe and acquisitiveness are running riot without a second thought for provenance or the unethical, dangerous possibilities of the trade, and almost zero fear of repercussions. Meanwhile, with the trade in large relics generally stemmed, online sellers are now prioritising smaller, cheaper antiquities that are both easier to ship and easier to loot. This trend is particularly concerning given that, as Mackenzie told the UNESCO conference, ‘the amount of archaeological damage or harm caused [by looting] isn’t necessarily reflected in the value of the object stolen’.

The hope, however, is that greater collaboration across the region – from multistakeholder discourse to research and knowledge sharing – will allow for greater preparedness and nimble action in the future. To name just one example, UNESCO Bangkok held a conference targeting collectors in 2019. Attendees were familiarised not just with legal issues and ethics, but also shown how to research provenances and check existing databases listing lost or vulnerable cultural objects – something that ‘good faith purchasers’ are duty-bound to do, according to the UNESCO convention. It was held at River City, the riverside antiques mall once associated with the trade in fake and genuine Khmer antiquities, but now working, alongside Thailand’s Fine Arts Department, to foster more responsible collecting habits.

Given the exceptionalism that looters of Khmer treasure have displayed through history, such attempts to sensitise collectors may prove decisive. Latchford excused his predilection for exquisite stone and metal gods and goddesses by saying, as he told the Bangkok Post, ‘they would likely have been shot up for target practice by the Khmer Rouge.’ A believer in reincarnation, he also justified his activities by saying that everything he collected had once belonged to him in a former life. Likewise, Malraux claimed until his dying day that the statues he plucked from Banteay Srei were rightfully his. Even Ficke, who returned his beloved Parvati after just one night, only did so grudgingly on aesthetic, rather than ethical, grounds. Although in his case, he did at least qualify this admission with a statement that still resonates: ‘How easy it is to diminish the world’s beauty by more than one has ever been able to add to it!’

The Prasat Nong Hong and Prasat Khao Lon lintels are on display at the National Museum Bangkok until 30 September