A famous author, a photographer on assignment, and a chasm of perspectives

On good days he writes an average of 100 words per hour. His staying power is just shy of three hours. Three hundred words on the most promising day: he works little by little. When the going is good, he feels like he’s descending. No… that’s the wrong image. While the hours accumulate, he does not feel like he is holed up, and so it isn’t descent but immersion. His desk takes on the character of a baptismal font.

He is writing his second book. Things aren’t going well. There are several false starts. Each sentence he writes appears inexact. He knows what meaning to convey but can’t quite discern the rhythm of the prose. If great prose could be measured in mileage, he’s done several days’ worth of journeying but all he can manage are inch-long strides.

He has to relearn the process of writing a novel, to master the twists of narrative, the right balance between fable and moral, truth and irony, character and event. He’s learning to tell the story of his people without cheap obfuscation or sliding into didacticism. He wishes, most of all, to work like storytellers of the past, in the oral tradition.

His first novel had been unexpectedly successful. Within two decades he’ll come to be known, because of the novel, as the father of modern African literature. But the afterlife of one book has no bearing on the ease with which the next is written – you write as if training yourself again to run the distance you once covered.

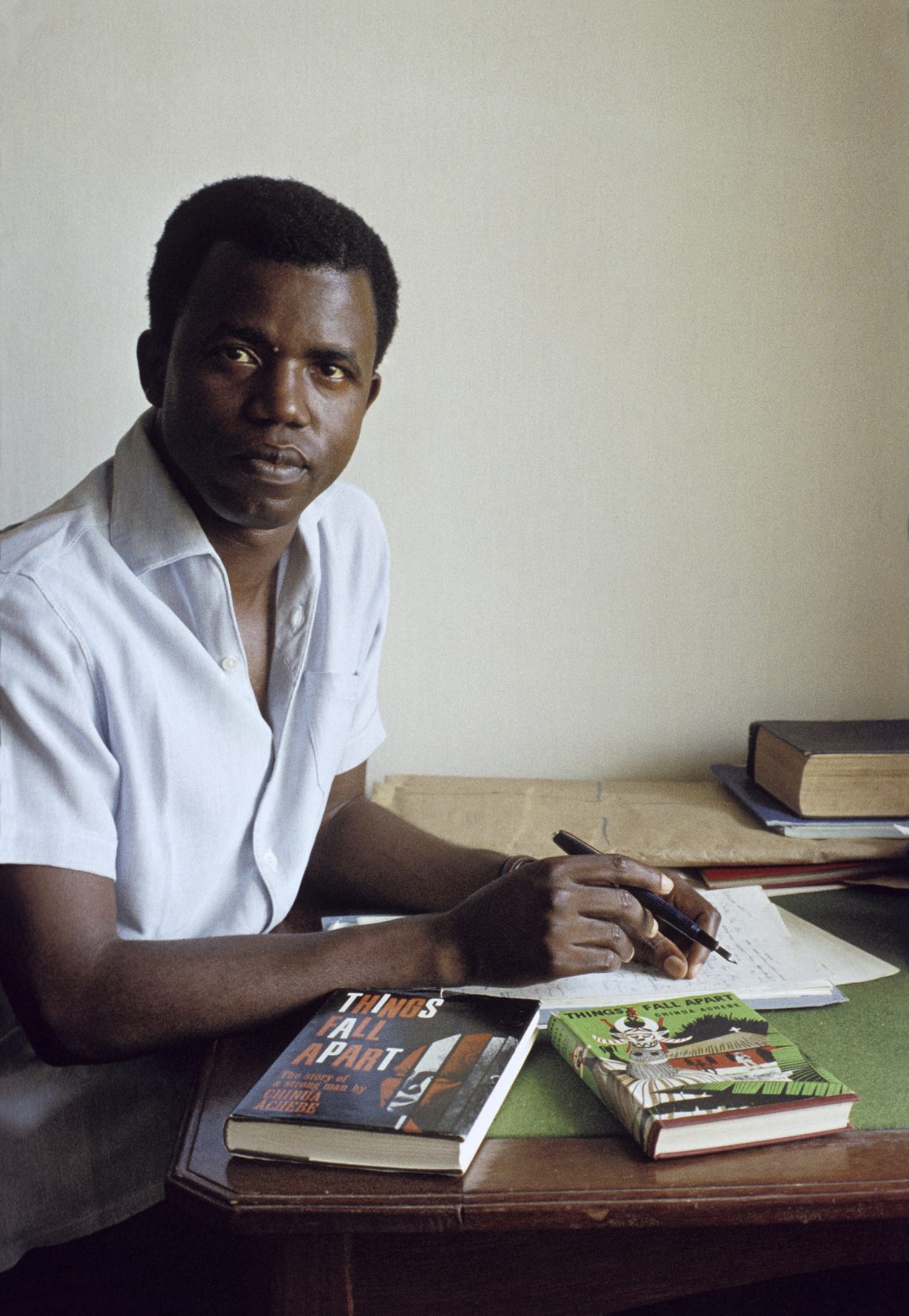

Yet sometime during this days-long stretch in which writing is strenuous and his purpose hazy he is offered a moment of distraction: a photographer visits his small flat, with the idea to picture him as a writer in modernised Africa. Eight photographs outlive the 1959 encounter. Four show him bent over his desk; four with his back straightened, facing the viewer.

The desk is small, even cloistered, and three books are visible: two editions of his famous novel, and a worn, bulkier book, likely the Oxford English Dictionary. In one of the photographs – one of those where he sits on a chair – you can make out a foolscap sheet and, zooming closer, the slender squiggles of his handwriting.

Many decades later, in 2013, Raoul J. Granqvist, a Swedish scholar who befriended the writer, reflects on the encounter between the writer and photographer. The writer has just died (the photographer long predeceased him). Granqvist clarifies that, despite how famous the photographs have become, they are framed by the racist assumptions of the series in which they are included. The photographer visited the writer as the second part of a commissioned trip for Life magazine. First he’d gone to Congo, where he took photographs meant to illustrate passages from books by white writers about the African continent, filled with clichés and stereotypes – including Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). Conrad’s book would be the subject of a reasoned rebuttal by the Nigerian writer in 1975, 16 years after this visit. And thus, Granqvist concludes, the distance between the photographer and writer ‘is measured in murky, racial moon years’.

But the writer appears to welcome the photographer with no such disillusionment. His eyes, when they turn to us, are kind and curious. Compliant and welcoming. His fight is neither with the camera, nor is it with tools such as English, the language of his colonial oppressors. Regarding English, he’ll later say he hopes to do ‘unheard-of things’ with it. Regarding the camera, what lie can it tell? We see him in one of the photographs as he might seem like alone, in the fight over exact words, straining to fill an empty page.