The artist’s life, work and exile is foundational to the history of Black-made contemporary art and the continuing struggle for racial equality in Brazil

‘You have my permission to produce The Emperor Jones without payment to me and I want to wish you all the success you hope for with your Teatro Experimental do Negro. I know very well the conditions you describe in Brazilian theatre. We had exactly the same… parts of any consequence were played by blacked-up white actors.’

So goes a letter, dated 6 December 1944, from the American playwright Eugene O’Neill to Abdias Nascimento, shown in a recent exhibition at Instituto Inhotim of work by the Brazilian artist, theatre maker, poet and activist. Nascimento had asked O’Neill if his tale of murder and power, written in 1920, might be the first work performed by his newly formed Teatro Experimental do Negro – the Black Experimental Theatre. Nascimento, then in his late twenties, had been part of a group of six Brazilian and Argentinian poets who had burned all their previous writing and embarked on a lengthy journey across South America in search of what they termed original American poetry. That is, writing that ignored the European tradition. In Lima they had come across a staging of The Emperor Jones, and while blown away by the pioneering spirit of the story, Nascimento, the only Black member of the group, bemoaned the fact the play’s Black lead was played by a white actor.

After the abolition of slavery in 1888 and the widespread intermarriage between races in Brazil, with no US-style segregation laws intact, the country was held up as a beacon of racial progress. In his 1933 book Casa-grande & Senzala (commonly translated as ‘The Masters and the Slaves’) the Brazilian anthropologist Gilberto Freyre describes an alémraça (a meta-race) more resilient than the sum of its parts. This was not however the day-to-day lived experience of dark-skinned Brazilians. Nascimento had started to strike out against racism, and the myth of Brazil’s ‘racial democracy’, from the age of sixteen. In 1930 the teenager moved from his home city of Franca to São Paulo to serve as a corporal in the army. In the state capital he got involved in the Brazilian Black Front, a radical activist group. One night during the Carnival of 1935 Nascimento and a friend were abused as they tried to enter a nightclub. A scuffle broke out. The police inevitably took the doorman’s side and the pair were arrested. Nascimento was discharged from the military and further convicted by a civilian court. His poetry pilgrimage took place while he was out on bail, and on his return he was arrested again. It was then that he began to formulate his thinking of what he called quilombismo: a mode of militant, collective Black autonomy, the name referencing the quilombos, remote communities historically set up by escaped slaves. Multi-ethnic Brazil was a front, after all, for a deeply racist policy of ‘whitening’ the population through selective immigration in which white workers from abroad were given financial incentives to come and make a new life. Or as Law Decree 7967 declared, ‘the necessity to preserve and develop in the ethnic composition of the population the more desirable characteristics of its European ancestry’. In prison Nascimento pondered further the staging of The Emperor Jones he had seen. From his cell he set about organising a convict’s theatre group, which on his release became the nucleus of the Teatro Experimental do Negro. Performed at the Teatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro on 8 May 1945, O’Neill’s work was the group’s first production in a programme that opened with a recital by the Black Cuban poet Regino Pedroso, and with Nascimento himself taking the stage to read Langston Hughes’s ‘Always the Same’ (1932). The choices were telling. Nascimento was not interested in merely fighting prejudice at home, but in tapping into the Pan-Africanist movement gaining traction in both North and South America, and across the Atlantic.

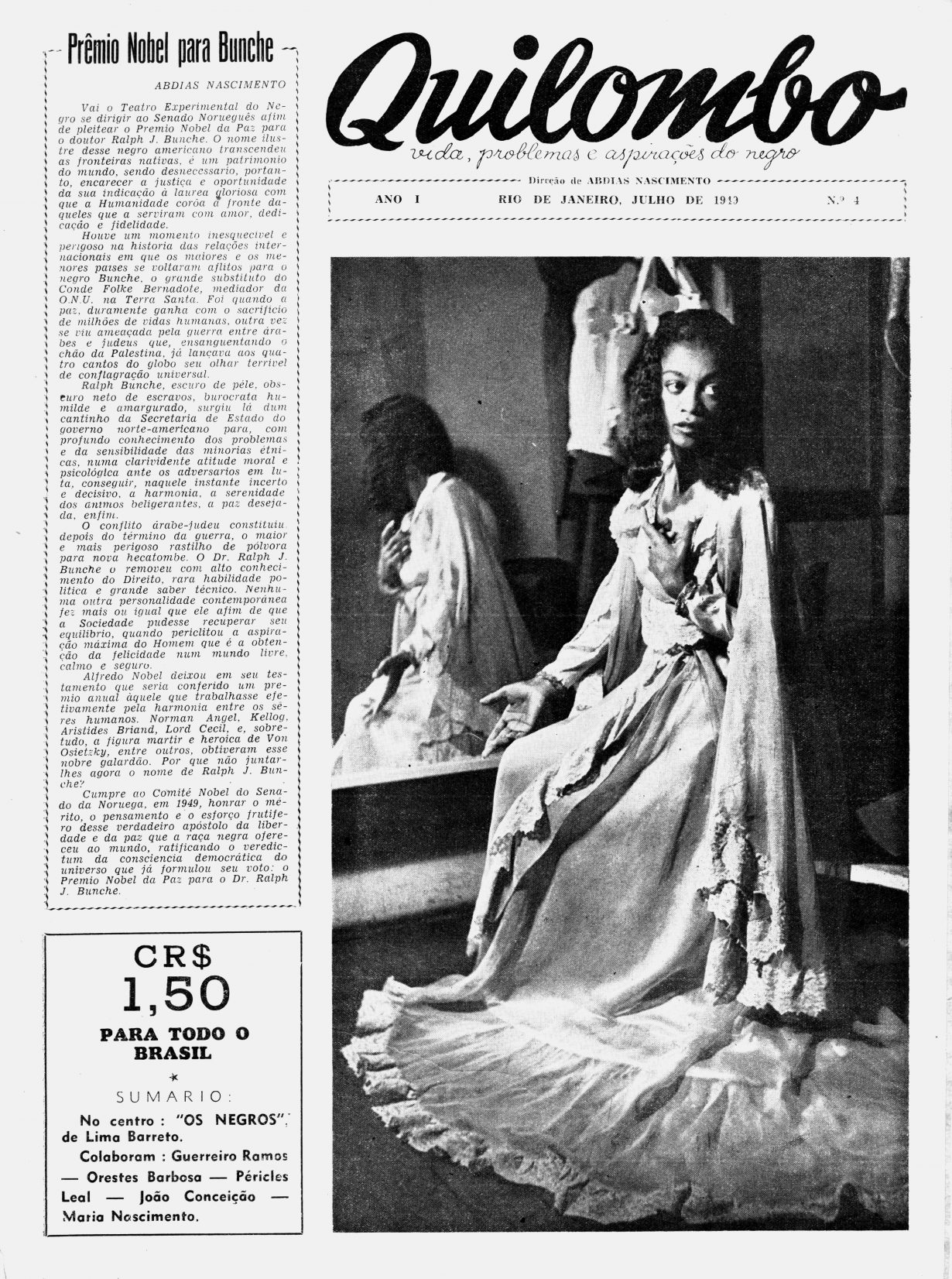

The group went on to stage many more performances across Brazil (including further works by O’Neill and Hughes, Nascimento’s own plays and Afro-Brazilian interpretations of classics such as Hamlet and Macbeth). The sets were invariably sparse, with questions of race, power and economic hardship delivered in what were praised as sharp, visceral performances. Yet theatre was just one part of the group’s activities: they published a newspaper, Quilombo; organised protests against racial discrimination both at home and in solidarity with Black liberation abroad (notably apartheid South Africa); and staged talks and conferences. In 1950 Nascimento and his colleagues opened the 1o Congresso do Negro Brasileiro (the First Congress of Brazilian Blacks), at which the group resolved to broaden its activities even further by opening the Museu de Arte Negra (the Black Art Museum), an institution that operated without a permanent home.

As well as delving deep into the theatre group’s archive of production photographs, scripts, posters and correspondence, the exhibition at Inhotim, an arts centre and sculpture park in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, displays rotating highlights of the Museu de Arte Negra’s collection in a pavilion that, with the blessing of Nascimento’s widow, takes its name. Despite never possessing a physical space, the museum collected art by Black artists who were, at the time, underrepresented in the country’s museums and art galleries (a problem that has persisted until very recently, the institutional reappreciation of Nascimento being part of this correction). In 1955 the museum organised a Black Christ Contest, in which artists competed for the best depiction of Jesus with dark skin. At Inhotim Cleo Navarro’s semi-Cubist oil on canvas, painted the same year, depicts the Son of God doleful and square jawed; likewise in Ecce Homo (1955), a reimagined Jesus by Quirino Campofiorito has his eyes closed in prayer and beard braided into two points. The new exhibition includes later works added to Museu de Arte Negra’s collection along the same theme: American LeRoi Callwell Johnson’s The Crucifixion (1996) is a fantastic Afrofuturist vision of Jesus on the cross against a strange supernatural vista. A semiabstract nude Black woman kneeling in prayer and an African Bakota mask (a motif used by Picasso) also figure.

The competition inspired Nascimento’s first forays into painting too. The medium provided him with a means to escape the oppression of Brazil’s burgeoning dictatorship: though still subject to censorship, the visual arts enjoyed far more freedom than other creative mediums. He made his first major body of work in 1968 – symbolism-heavy canvases, largely in acrylic, that intoxicatingly mix modernist abstraction and African figuration – just as new laws of Brazil’s four-year-old dictatorship imposed widespread repression. As Nascimento started to paint, the national congress was disbanded, newspaper offices were raided, musicians and filmmakers went into exile. All scripts were censored, with cuts and bans meted out on the basis of politics or morality. A production of African-American writer LeRoi Jones’s Dutchman (1964) was banned, along with four scripts by Brazilian playwrights that year. The industry went on a two-day strike after key lines of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) were cut by the censor.

Within the year Nascimento too had gone into exile, first to the US, where he staged his first painting exhibitions (he didn’t exhibit in Brazil until 1974, the end of the so-called Years of Lead), and then to Nigeria. Painting was also conducive to his circumstances. ‘Inhibited by my poor grasp of English, I developed a new form of communication,’ he said. Nascimento never liked speaking English, having already been colonised, he said, by Portuguese. ‘I could paint, and by painting I would be able to say what no words could say.’ His 1969 exhibition at New York’s Harlem Art House was titled Teogonia afro-brasileira, a perhaps contradictorily European-centred reference to ‘Theogony’ (c.730–700 BC), a poem by Hesiod describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods. For Nascimento it was the orishas deities of Candomblé that were his subject matter. Another recent exhibition, this time at MASP in São Paulo and dedicated to the artist’s paintings, opened with one such work: in flat blocks of uniform tones an orange peacock is shown, sharing the canvas with a large butterfly in similarly warm tones. A woman with the lower body of a fish lies to the bottom of the frame, while to the right of her a bull-like head (but odder, more alien) stares straight ahead. The title of the 1972 painting names several Afro-Brazilian gods: Iansã, Obatala, Oxum, Oxossi, Yemanjá, Ogum, Ossaim, Xangô and Exu. Iansã, mother of storms, also appears in another work of the same year, conjuring up a great wind and holding a decapitated head aloft. Meditation no 1 and Meditation no 2 (both 1973) feature Apis, the sacred bull, his eyes dilating respectively pink and green, each rendition featuring a burning sun emanating from the animal-god’s temple. In the second work the bull’s features are more angular; both are strange and unsettling compositions. Other works might be mistakenly labelled abstractions, but are in fact amalgams of religious symbols. In Eshu and Three Tempos of Purple (1980) two tridents curve inwards encasing three floating purple orbs – an ode, the title suggests, to the trickster god inherited from the Yoruba people. The use of such symbols is part of a strategy, Nascimento wrote in 1980, to address ‘the urgent need of the Brazilian Black people to win back their memory’.

For Nascimento spiritual liberation and social freedom were inextricably linked. The works were political gestures despite their cosmological subject matter: they asserted Black culture as foundational despite, as he explained in a 1976 speech in Senegal, the fact that ‘we are dealing with the more or less violent imposition or superimposition of white Western cultural norms and values in a systematic attempt to undermine the African spiritual and philosophical modes. Such a process can only be described as forced syncretization.’ A series of paintings from the 1990s incorporate the Adinkra symbols, ideograms originating in Ghana that communicated various philosophical ideas (and were also used as code language by Black African slaves to communicate clandestinely). Living abroad, Nascimento considered himself to be in double exile: both from Brazil and ancestrally from Africa. Much of his painting, in exploring African cultures that migrated and mutated, can be read therefore as establishing a Black homeland that operates beyond the nation-state borders defined by colonialism. In a pair of paintings Nascimento plays on flag insignias, refiguring them using Candomblé symbols. In Okê Oxóssi (1970) an arrow shoots through the central blue orb of the Brazilian flag; while in Xangô Sobre (Shango take over, 1970) an axe divides the us Stars and Stripes. These works are made in conscious allusion to Marcus Garvey’s 1920 Pan-African flag: most obviously in Quilombismo (Exu e Ogum) (1980), which features the symbols of the two gods painted in black over the red and green of Garvey’s earlier liberatory banner.

Nascimento was not a marginal figure: he rose up through the ranks of academia in the US before, on his return to Brazil in 1983, becoming first a federal deputy and then senator for Rio de Janeiro. He was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1978, and a year before his death in 2011. The Brazilian artworld is increasingly and belatedly investing time and resources into Black-made contemporary art (though the internationalism that Nascimento strove for remains scarce) and his work provides part of the foundations from which to build that lineage. Blackface is no longer acceptable in the theatre. Yet his institutional reappraisal comes as so much of what he strived for in wider society remains unfinished business. Recently, fly posters featuring cheap reproductions of Okê Oxóssi and Quilombismo (Exu e Ogum) started appearing beneath flyovers and on the cluttered concrete walls of downtown São Paulo. They aren’t advertising any exhibition, however. Above the work is printed the rallying cry, made as the country goes to the polls for the presidential elections in October: ‘VOTE NA PRETA’ and ‘VOTO ANTIRRACISTA’ (‘Vote for Black’ and ‘Antiracist Vote’). No specific political group or candidate is referenced; it is a call to action that transcends party politics. They do suggest however that, far from disappearing into art history, Nascimento’s message continues to empower the fight against oppression.

Instituto Inhotim is hosting a changing programme of exhibitions relating to Abdias Nascimento’s work through December 2023