The historian and critic Eva Díaz’s new book, After Spaceship Earth, follows R. Buckminster Fuller and how his legacy has shaped contemporary art

Jumping off from The Experimenters (2015), her wonderfully readable history of Black Mountain College and its remarkable aggregation of some of the twentieth century’s major artistic and design talents, historian and critic Eva Díaz, in her new book, focuses on one of those talents: R. Buckminster Fuller. Fuller taught at Black Mountain from 1948 to 1949, and is styled as the trunk of a family tree whose blooms Díaz sniffs out in all sorts of contemporary art practices of the past decade.

Fuller is a fascinating figure, and for Díaz he embodies both the good and the bad of American techno-utopianism. For Fuller, technology was an unalloyed good, as was the imperative to use it more efficiently and equally distribute resources around the globe. But Fuller was also a us military contractor (an unalloyed bad for Díaz’s wing of the progressive art-and-design caucus). Various of his dome designs were bought by the US military for easily transportable and constructable housing, both for people and for surveillance equipment, as with the Defense Early Warning (DEW) installations that pepper 4,800 kilometres of the Arctic. In After Spaceship Earth, Díaz sets for herself the task of showing how contemporary artists have been exploring both the promises and compromises of Fuller’s legacy, which she nicely dubs the ‘Fuller Effect’.

Much of that exploration comes down to how, when and why contemporary artists have presented, or represented, domes in their work. And indeed, domes abound: Díaz narrates how Fuller’s famous geodesic domes figure as dystopian escape pods in works by Mary Mattingly and Oscar Tuazon; as sites for critiquing what Díaz calls ‘modern adaptive information flows’ in works by Ben Coonley and Jacolby Satterwhite; as channelling a communitarian imagination, from their centrality for Drop City, a 1960s Colorado hippy commune, to MoMA ps1’s corporate-sponsored VW Dome event space, which was in service from 2012 to 2020; and as portents of a totalitarian information space (from the dew to Starlink) that is revealed and critiqued by artists such as Hito Steyerl and Trevor Paglen.

For all of the excellent snippets on Fuller and his effects on both art and pop culture – particularly noteworthy here is Díaz’s linking of the dissociative experiences of domed cinema spaces, such as the 1963 Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles, to Douglas Trumbull’s revolutionary FX work for the ‘stargate’ sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – they remain just that, snippets, with in some cases only the most tenuous connections to the more contemporary artists and debates that hold Díaz’s interests.

One has to ask, for example, why nothing is written about Ruth Asawa, one of Fuller’s students at Black Mountain College during the 1940s. Or what about Norman Foster, who met Fuller in 1971? He comes in for only a single mention, and only as an avatar of the excesses of space privatisation, though Foster is arguably the figure today who is manifesting the full scope, both good and bad, of Fuller’s technoutopian visions.

Another way to put this is that After Spaceship Earth would be a very interesting exhibition, but it is not entirely convincing as either history or criticism. When in the second half of the book Díaz exchanges Fuller for legendary funk musician and Afrofuturist Sun Ra as a touchstone for contemporary art practices, what were once ‘effects’ traceable through a loose but tangible genealogy become mere thematics. Any work of the past decade that invokes space or time travel as an allegory for racial, feminist or decolonial politics might be included, and the writing suffers. For example, two paragraphs on Neïl Beloufa’s 2007 videowork Kempinski – the only two this otherwise exceptional artist gets in the book – read like an overindulgent wall text.

In these latter sections, description comes to trump analysis, as works of art become illustrative rather than illuminating, artists are ‘profiled’ and chapters close with shopworn progressive mantras about ‘injustices’ being met with ‘new speculative imagination’ and ‘radical forms of invention in performance and art production’. These themes are more redolent of establishment exhibition culture, here captured between the covers of a book, which doesn’t feel very new or radical at all.

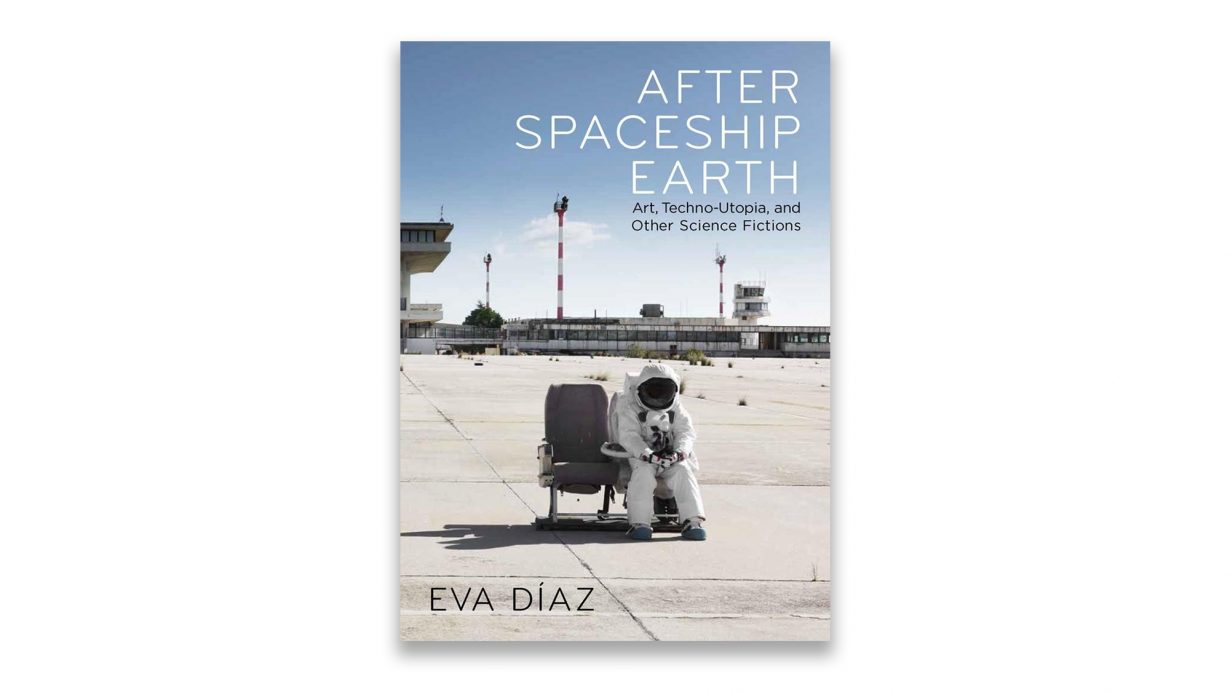

After Spaceship Earth: Art, Technology, and Other Science Fictions by Eva Díaz. Yale University Press, £45 (hardcover)

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.