Testing the Objects of Affection at Alison Jacques, London is defined by the relationship between other-worldly and earthbound objects

Beautiful, deadly things inspire Alison Wilding. Some of her art objects lean towards ethereality. A delicate, orb-like Gobstopper 5 (2020) made of silver-gold wire, floats, suspended from the ceiling on a transparent thread. Others are earthbound. Hocus Pocus (2022) features a rusty orb atop a serrated disc-like form fixed to the wall. Dirty, dark, dangerous. If the first orb is beauty, the second is death. This relationship between other-worldly and earthbound objects, between symbolism and materiality, is one of the structuring principles in this retrospective show of the British artist.

Wilding rose to prominence in the 1980s as one of the artists associated with ‘New British Sculpture’, a group styled by critics and curators that included contemporaries such as Richard Deacon, Shirazeh Houshiary and Anish Kapoor. Reacting against the predominance of Minimalism and conceptual art, theirs was an alternative approach to sculpture characterised by an eclecticism of materials and methods.

Through the 23 works presented, Wilding manipulates the interaction between viewer and sculpture, continually varying the height of floor-based and wall-mounted works. Belvedere (2011) resembles a water-well made from one-metre-high white zig zag walls, from which a curious purple sphere peeps. From another position the sphere turns out to be a fibreglass balloon propped up on a gnarled silver-painted twig. Whereas Belvedere contains space, Breaker (1985), a matt-black freestanding steel trapezoid, fractures it. Vertical and mostly flat, it is curled slightly at the edges, propped up by a curious flipper visible only from behind.

The closest Wilding gets to a plinth is a selection of six small sculptures arranged on a table. Several hint towards stalled motion and flight. Killjoy (2015) comprises a bleached pheasant feather threaded through a dark-grey orb. Once used in flight, the feather is now bound to heavy iron, laid to rest atop a bowl-like iron base. The themes of weight and flight are again evoked through Badapples (2014). Two bronze apples are fused at their bases, grounded on the surface, provoking thoughts of Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity. Like the object of its title, Solenoid (2015), the sculpture resembles an electromagnet, a sort of dark oblong bobbin, but is set in iron and wax, stifling any possibility of electricity or motion. Two dark, cylindrical, vase-like receptacles, Pair (1994), preside over this curious selection. Wing-like shapes protrude from the top, guardian angels watching over the two hand-sized alabaster cuboids that sit at their feet. These latter works, Press 1 and Press 2 (2006), are marbled in shades of coffee, clouded cream and sienna, their earthen colours inviting quiet reflection, pausing the rhythm of the room, much like the stalled flight to which many works hint.

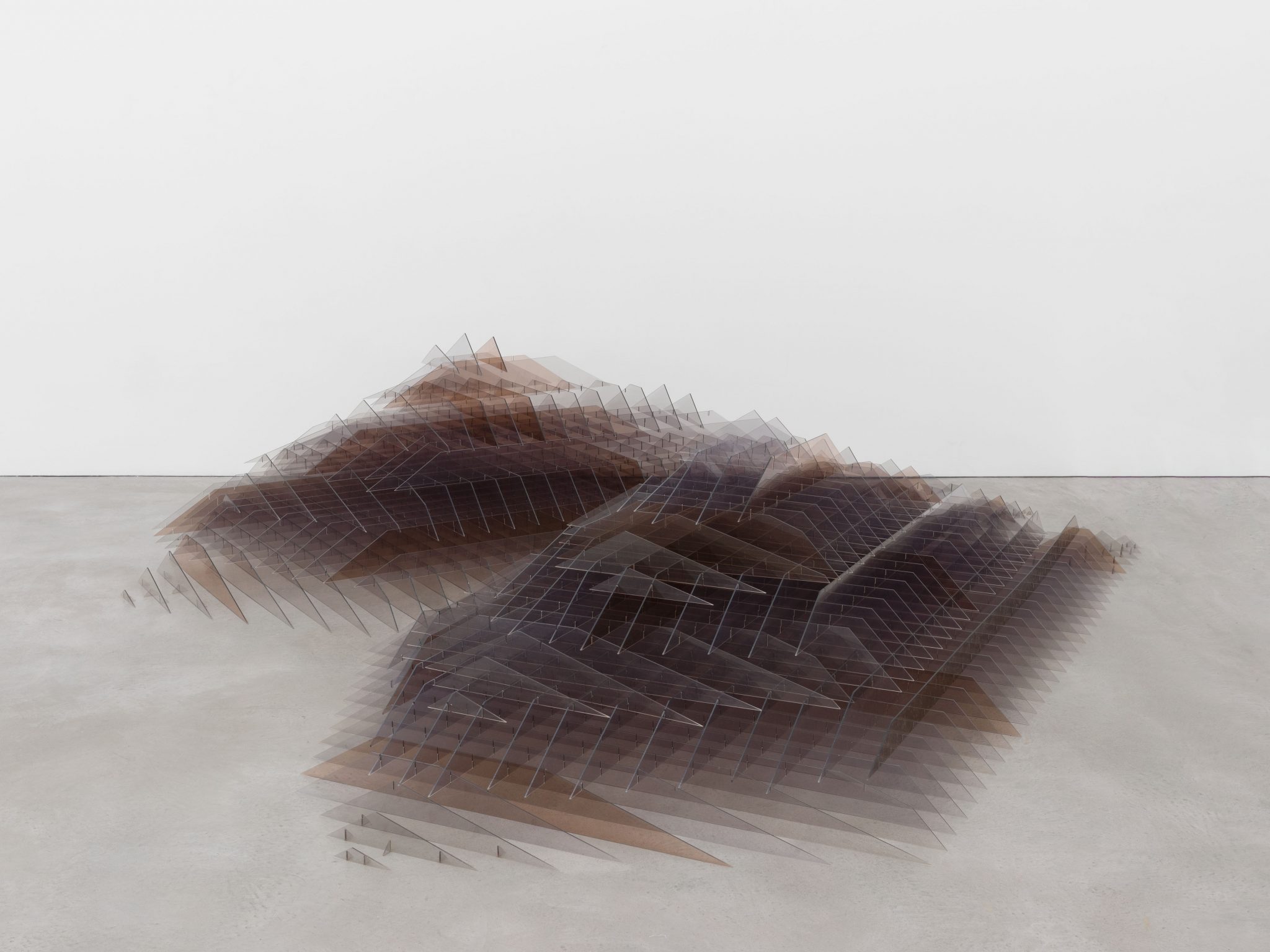

In the second gallery, artificial light floods down from the ceiling, a stark contrast to the sombre works that possess the space. The stand-out work here is Terrestrial (2003). Two prisms rise from the floor to shin-height. Dark, shifting masses from afar, these are made of hundreds of interlocking triangular and trapezoid transparent plastic slats. Shadows shift through their transparent grey and brown planes, absorbing light into them. Drowned (1993) is the other alien presence in the room. Like Terrestrial, it produces an uncanny sense of silent presence, altering with each changed perspective. Shiny, almost black, its conical shape is made of deep-green acrylic. Raised slightly off the ground, it appears to levitate, an eerie green halo at its base.

Wilding takes seriously how different forms affect our sense of physical presence, provoking visitors to orient themselves in relation to the changing moments of visibility and concealment in her works. Leaving back through the first room, you confront the wall piece Ahem (2020), hung at face height. Its alabaster body and foam cone arms, finished with a spherical head, resemble a crucifix. This final work confirms what one suspects of the exhibition: underneath the playfulness, materials dance between worlds.

Testing the Objects of Affection at Alison Jacques, London, 20 September – 26 October