Saban glitches her way to a multidimensional critique of how we assign value

Chat GPT declines to say whether Analia Saban is a painter, a sculptor or a weaver; instead it remarks that Saban is ‘conceptually rich’, and when asked for clarification, the bot suggests she is ‘rich in concepts’. Another question simply yields a return to the first answer. Granted, it isn’t easy to say what kind of art Saban makes: works on view in her recent Los Angeles exhibition, Synthetic Self, held jointly at Sprüth Magers and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, employ laser cutters, machine looms, marble slabs, screenprints and graphite panels to explore the proliferation of artificial intelligence – a new subject in Saban’s singular practice.

Saban’s work is better defined by her consistent critical inquiries than by medium alone; her work collapses the stratifications between domestic, private modes of production – seen in weaving or in ‘work from home’ industries enabled by consumer electronics – and those in the public sphere, from male-dominated modern art practices to technology used in mass manufacturing. Saban’s tapestries, objects and wall reliefs highlight the flawed nature of technology, emphasising the ways in which machines – and their malfunctions, like Chat GPT’s ‘conceptual’ ouroboros – both enable and destroy. Textiles disintegrate, canvases break and AIs glitch: Saban traces a material history of creative processes in which machine error is, as they say, a feature, not a bug.

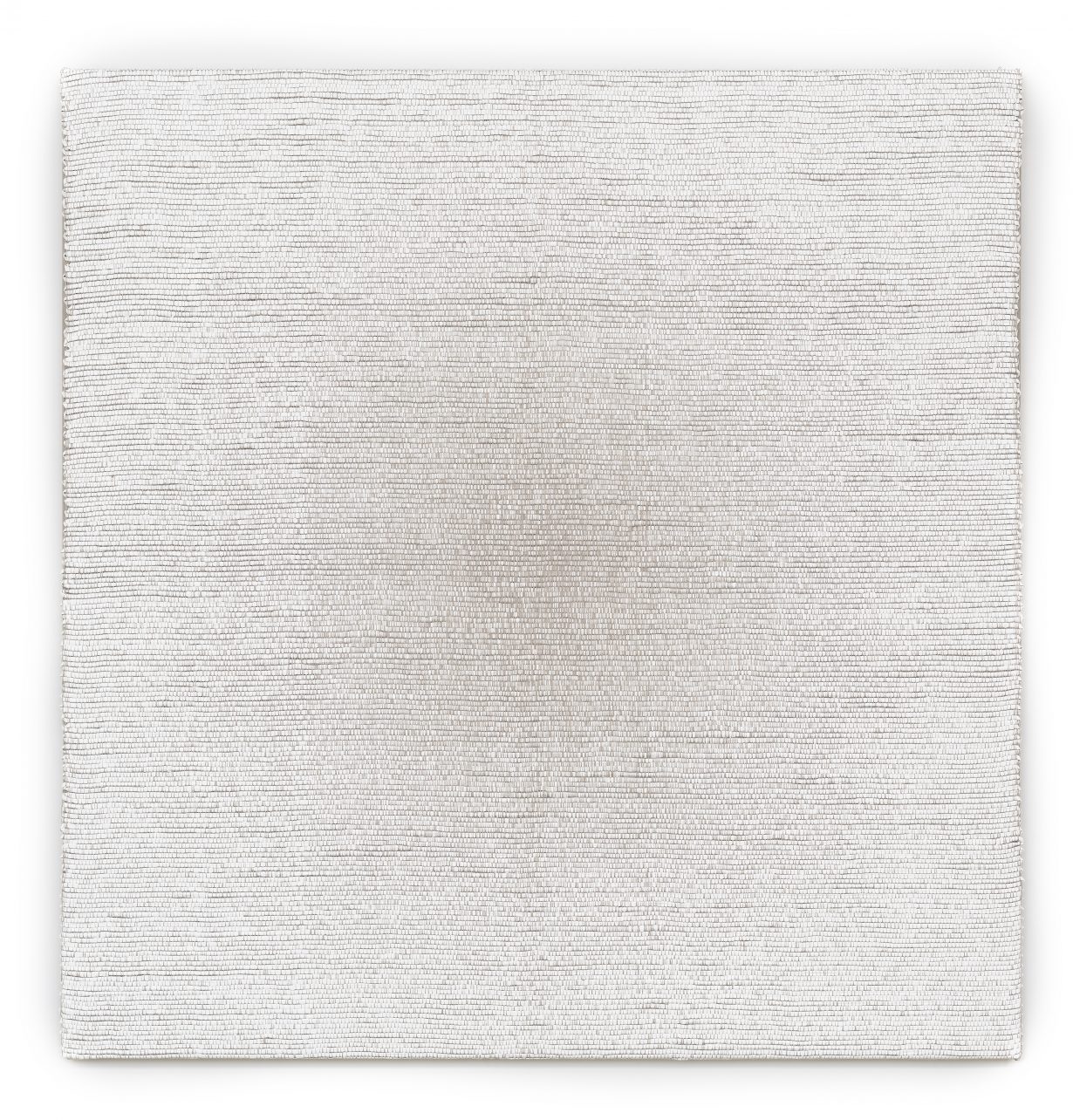

Saban first gained artworld attention with her tapestries, which use mechanised methods to disrupt antiquated, often gendered divisions that defined textiles within the arts. Historically, painting and textiles have been segregated along gendered lines: domestic women composed weavings that were shown, if at all, in craft and ‘folk’ exhibitions, while studied – and moneyed – men made paintings for salons and museums. Through her innovative use of materials, Saban combines the two disciplines, subverting art-historical lineages in the process: Woven Olympia, Gray (2021) employs a computerised loom to weave dried acrylic paint ‘threads’ with raw linen fibres, forming a painting/tapestry based on Édouard Manet’s infamous Olympia (1863), the original reclined figure distilled to a wavy grey outline. The same mechanical operation composes Woven Radial Gradient as Weft (Linen on White) (2020), a white weaving with a faint, shadowy centre that recalls the painterly abstractions of Ad Reinhardt or Mark Rothko. Saban’s sly interventions force reconsiderations of discipline in the current industrial age, destabilising systems of value used to relegate women from fine-art arenas.

In sculpture, Saban’s attention to the intimate connection between machines and creative output turns luxury goods, like art, into symbols of mass production. Claim (from Chesterfield Sofa) (2014) features a large canvas draped in beige cloth, the thick fabric extending into the buttoned divots of a tufted couch placed below. Saban’s ‘claim’ ties together two often expensive pieces of decor – art, furniture – by their raw materials, reducing these pricey items to their simplest structure: fabric, typically manufactured in bulk, stretched over a stock frame of wood or metal. A series dedicated to unearthing the material histories of colour yields similar results: in Five Thousand Years of Blue (from Lapis Lazuli to Tesla Door) (2021), a swatch of pure pigment extracted from a Tesla’s exterior extends diagonally across an unprimed canvas, a line that stretches from a pile of lapis lazuli rocks at the wall-hanging’s top edge to the glossy, royal-blue car door at its bottom. Saban’s painterly brushstroke unites the unprocessed stone with its most ostentatious form through artistic gesture; her recombination revealing the substances obscured in the production of privately owned, fetishised commodities. Brands typically mask manufacturing processes from their market; in her artwork, Saban deconstructs these products to emphasise each object’s materials, a focus that lays bare the foundation of the luxury sector.

Saban’s subtle critiques of capitalist production pair with more literal manifestations of failure within the works themselves; in her wall-based reliefs and tapestries, machines both create and fracture each delicate composition. Saban’s contemporary tools are incompatible with natural materials: in Cooling Rack (6 × 6), Pine Wood #2 (2023), line-art illustrations of computer fans are cut by a laser-sculptor into sheets of pine, the wood occasionally shaved so thin that large fragments break away – rendering the fans difficult to discern. In Distressed Canvas Circuit Board (with Component Rubbings and Punctures) #1 (2018), the impression of a motherboard into the back of a stretched canvas creates a landscape textured – and eventually ruptured – by technological infrastructure, a piece of circuitry ripping through the fabric’s membrane. Brushstrokes (Dandelion Field) (2014) reveals the fragility of digital photography subjected to editing software: the diptych displays a closeup view of a meadow, with fragments of grass and flowers removed, their pixelated remains scattered haphazardly across the frame’s blank righthand side. Electronics shape each artwork, but their effects are often as detrimental as they are productive.

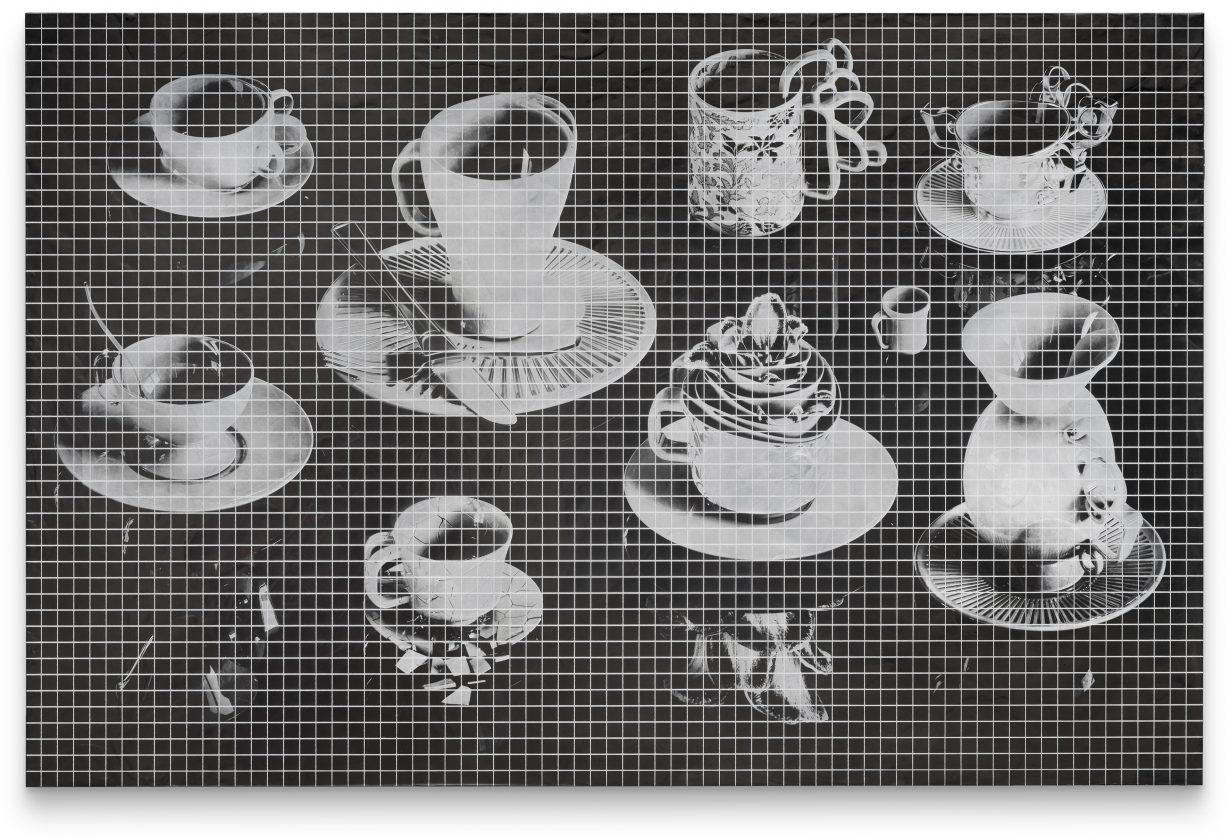

Saban’s most recent pieces use a new roster of materials to explore the faulty knowledge generated and disseminated by digital tools. In Flow Chart (Painting a Cup) (2023), Saban scrawls a formula that could be used to create a painting of a teacup across a black canvas, one reminiscent of classroom chalkboards. These diagrams – similar works on view at Sprüth Magers chart the steps required to create portraits and landscapes – outline the iterative processes that software might run to produce artwork. The results, however, stray from the assignment: the wall-based, multimedia Grid Method: Tea Cups (2023) depicts photorealistic mugs with extra handles, and malformed, unusable vessels, their computer-generated forms laser-printed across a gridded, rectangular square of graphite. Saban represents these ‘wrong’ digital renderings with materials typically employed in early childhood education: AI’s reimagined ‘tea cups’ appear across a top layer of encaustic wax that coats a large graphite panel, two substances usually found in pencils and crayons. Accompanying works use the same altered school supplies to explore the vast amounts of data gathered online, often with nonfunctional results: Self Portrait: (@#&%/,.* (2023) lists the keyboard characters in the piece’s title in the vague shape of a face; their symbols recall the structure of binary code, but they possess no practical use. Saban’s graphite and encaustic works join teaching tools with glitchy technology, situating malfunctioning devices at the core of the production of more ineffable commodities: data, facts and images.

“This is how reality feels for me right now,” Saban remarked at a recent viewing Synthetic Self. She gestured at Prompt Drawing: Deep Fake (2023), a laser-printed photographic work that depicts three close-but-not-quite views of Saban’s own face generated by AI, their forms emerging from a darkened graphite background. Saban’s joke commented on the banal intermingling of two once-separate worlds, that of humans and machines. The overlap proves central to the way we conceive of both abstract and physical goods, enshrouding them in a veneer of cryptic, manufactured perfection. Mined rocks become the sheen on a Tesla’s door or the paint in Manet’s Olympia; a formula dumped into AI can produce an artful still-life or an NFT-ready portrait. In Saban’s work, though, these structures feel both fragile and fallible: fragments of wood break from a replica computer fan, and ‘deep fakes’ are inaccurate to the point of absurdity. Saban’s skill lies in decoupling products from their mythos, resulting in works that portray technology – and the powerful, totalising systems they facilitate – as fundamentally broken. ‘Rich in concepts’, indeed.

Synthetic Self is on view at Sprüth Magers and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Los Angeles, through October 28

Work by Analia Saban can be seen in Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, LACMA, Los Angeles, through 21 January