On Clogger Lane at LUX, London memorialises and wards against forgetting a British past

The scrawled red overtitles that open On Clogger Lane read, ‘Much that once was is lost, for none now live who remember it’. Andrew Black’s hypnotic hourlong video essay exists in a lineage of British artist film that seeks to memorialise the past and ward against forgetting, from Patrick Keiller’s Robinson in Space (1997) to the films of Duncan Campbell or Elizabeth Price; the unearthing of documentary sources, the recording of oral history, in the service of a more mythological sense of its subject. For while social history appears as the immediate content of Black’s film, there are altogether stranger and less certain questions that run below that surface: of the fragility of memory, of the way that the past might no longer make sense to us and how forgetting is a political choice made by those in the present.

The locations we see in On Clogger Lane are in the landscape of North Yorkshire, a region of rugged hills, heathlands and moors, a place of enduring community and cultural tradition long romanticised in British culture. It opens with amateur archaeologists examining large grey stones found on a sunny heath, scraping chalk into indentations in the stones to reveal what might be a symbol – some primitive figure or astrological sign, or… what exactly? It might be a sign from the deep past, or it might be a projection of what the archaeologists want to see.

Unearthing what lies beneath the surface becomes On Clogger Lane’s obsessive motif: accounts of the building of water reservoirs in the last century and the consequent flooding of entire villages; the black-and-white archive image of a church half-submerged, and a woman explaining how earlier generations of her family lie in graves now deep underwater, segue into conversations about the social histories of those buried. As a group clear the brush from an abandoned graveyard, local-history experts recount these stories of working-class Britain; of poor women committed to asylums, of adolescents brought from the big cities, whose excavated remains showed signs of injuries from working in local mills. But everything is now ‘at the bottom of the reservoir’, the blood-red titles repeatedly tell us, while archival footage turns our attention to quarries and quarrying. Under Black’s documentary attention lies a tenebrous, coldly woozy soundtrack of drones and cymbals that interjects a weird intensity: to the sound of ponderous gong chimes we see quarry faces dynamited, black rockfaces ballooning from inside, as if called to destroy themselves by nothing more than the gong’s reverberation.

As the film unspools, it becomes clear that submersion, burial and excavation, as both present-day acts and metaphors for knowing history, become merged. One layer of water or rock or earth offers up glimpses of moments of human history, but all these are swallowed up by the ‘deep time’ (as one interviewee puts it) of the land. In the film’s second half, the relatively objective tone begins to fracture into something more paranoid, as the stories turn to myths of witchcraft and hidden forces. This brings us to the surreal view of RAF Menwith Hill listening station, with its array of white ‘golf-ball’ domes used by the US for surveillance, and whose activities (including telecoms eavesdropping) have long caused controversy. We hear from veteran women peace campaigners of the 1980s, now elderly, who took inspiration from the Greenham Common antinuclear missiles campaign in their own protests against the US presence at Menwith Hill.

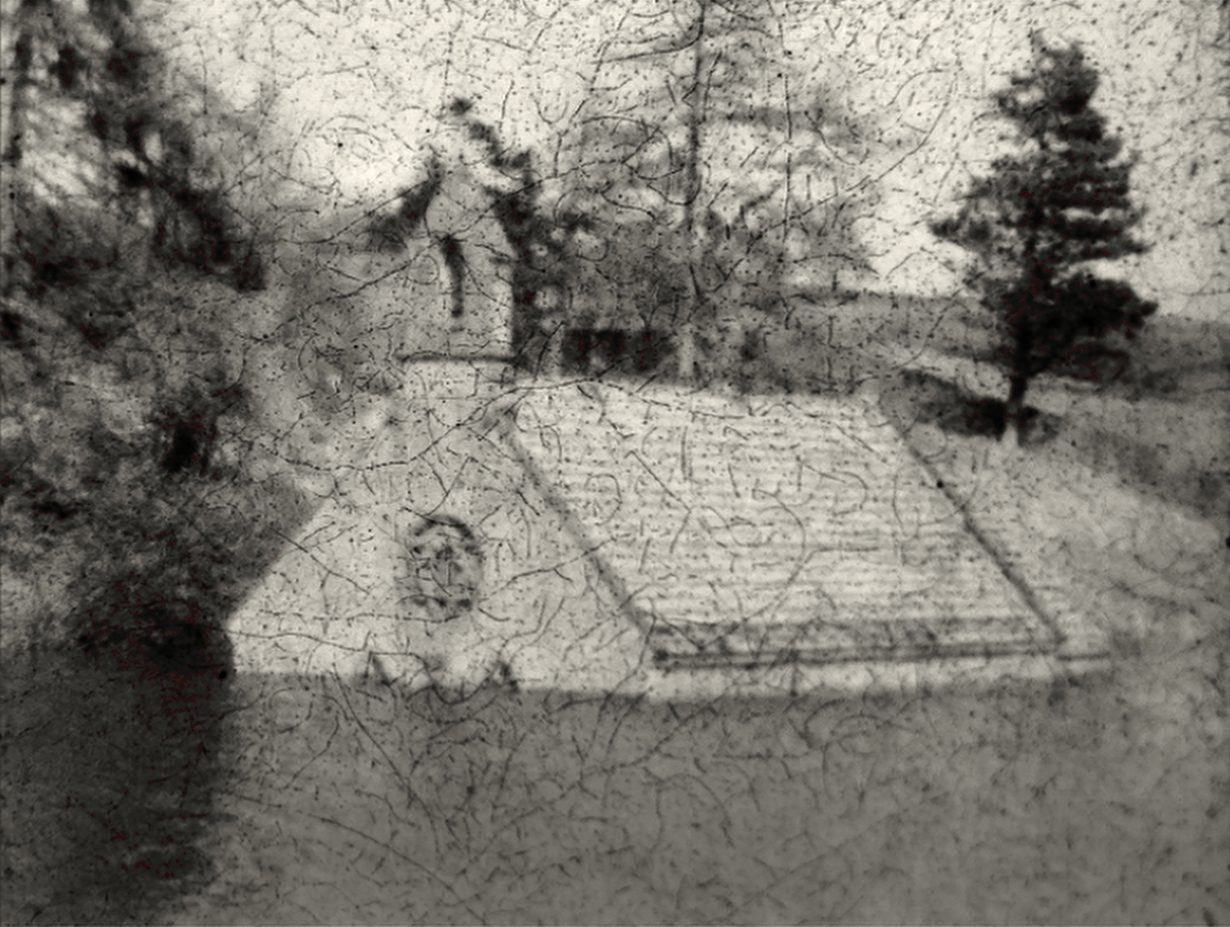

But there’s a sense of anachronism to these reminders of (relatively) recent history, as if the more Black tries to rescue these testimonies, the more their reality seems to recede, becoming something alien. “There’s very little protest about it nowadays,” says onetime campaigner Anne, ruefully. This melancholy and disconnect drifts through On Clogger Lane, as Black introduces uncanny synthesised choral voices, one singing the thirteenth-century Middle English verse ‘Foweles in the Frith’, another the twelfth-century French poem ‘Ja Nus Hons Pris’, both lyrics wistful reflections on loss and despair. Closing with a shot of Black himself marking out two carved symbols of concentric circles found on a heathland rock, with Menwith Hill’s domes in the distance, On Clogger Lane is full of surfaces and subterranean opacity, in which history seems doomed to disappear. It’s all the more striking for treating the documentary image itself as a kind of decaying matter – locations and people are seen receding back through a history of the medium – from clean digital, to striated, jittering analogue video, to cracked and disintegrating cine film. Retrieving the layered truths of a place, the film seems to suggest, may no longer help us make sense of our moment in time, however much we look back.

On Clogger Lane at LUX, London, 19 January – 10 March