As her largest project yet opens at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, the artist – known for her work with scent, olfaction and living micro-organisms, and for her extensive collaborations with biologists and technologists – discusses how the pandemic has changed her approach to life and practice, and why she’s not too attached to ‘survival’

Retrospectively, Anicka Yi’s artistic trajectory looks remarkably focused. She rose to prominence in New York during the early 2010s with a body of works that leaked, seeped and wafted around galleries, demanding an engagement from her viewers that was at turns humorous, sensual and sharply cerebral. She became known for combining unusual chemical and organic materials, often perishable, with a wry autobiographical drive. A case in point is Sister (2011), a funny, figurative work of sorts comprising a red cotton turtleneck crowned by a bouquet of tempura-fried flowers, their abject glory temporarily fixed in crystalline growths of panko and batter.

In some ways, this knowingly subversive curating of consumer signifiers was characteristic of the late-capitalist, post-conceptual gestures of the early 2010s, but Yi’s work also alluded to an interest in another reality. In works like Sister, language, subjectivity and chemical transformations effortlessly converge, as if to suggest the entropy underlying it all. On the occasion of SOUS-VIDE (2011), her first solo show at 47 Canal, Yi said she wanted audiences to approach her work with “a presentness of biological and intellectual receptors” while speculating about “[exploring] more biotechnologies. Cryogenics, grafting, impregnable materials”.

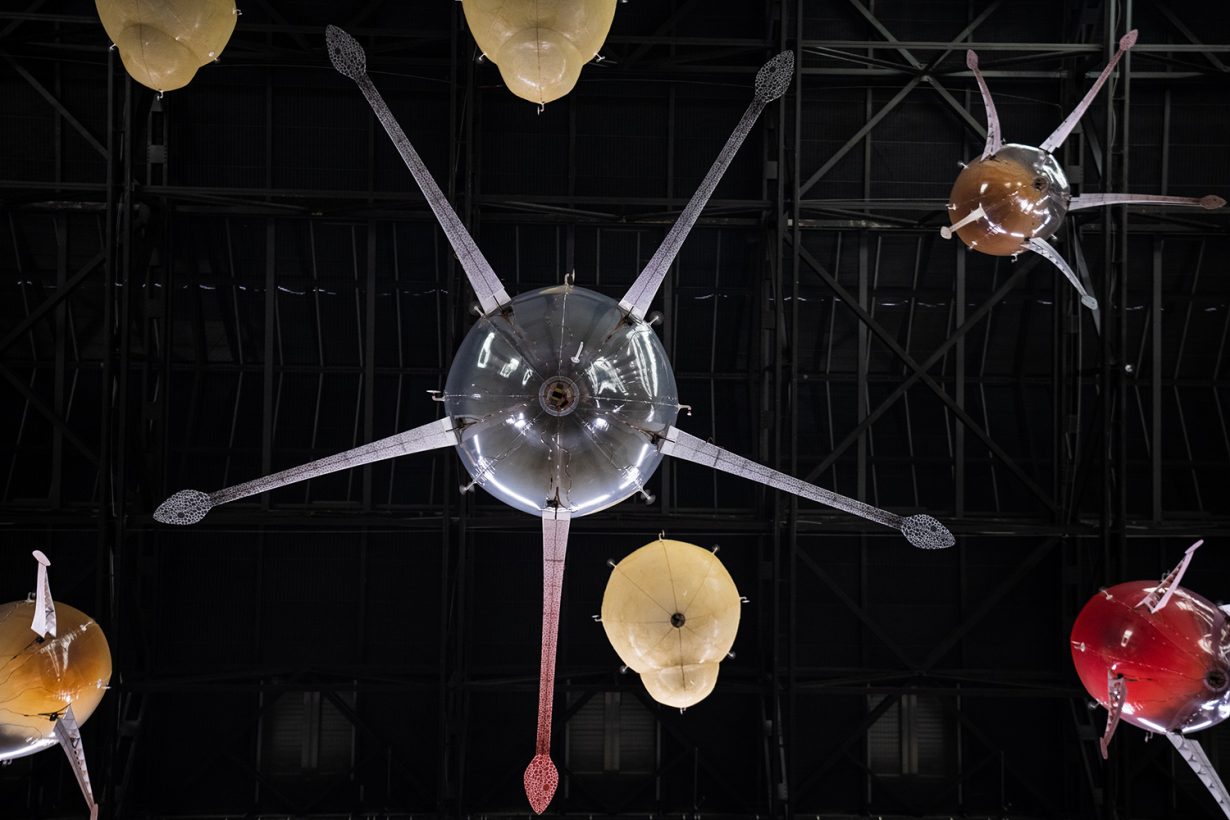

In the decade that followed, she did just that, becoming known for her work with scent, olfaction and living micro-organisms, and for her extensive collaborations with biologists and technologists. After a lauded solo show at the Guggenheim in New York and a multiyear residency with microbiologists at MIT, the artist’s commission for the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall – their largest project yet – opens this week in London. The installation was, she tells me tentatively, developed in collaboration with three different types of engineering teams.

There’s a large, blurry fly hovering around during the video call, but Yi doesn’t seem to mind. “There are lots of insects upstate,” she tells me. As it turns out, Yi and her team have been working from a compound in upstate New York. To our mutual dismay, the Turbine Hall commission remains under embargo, so we discuss the world around her instead.

GARY ZHEXI ZHANG So you’re out in the forest.

ANICKA YI In the woods, yes. You know, I was just talking to my research director this morning – she’s remarking upon a bird on her windowsill because she’s in the house next door. I just warned her, jokingly, that that bird is probably carrying lots of ticks. And we were talking about how sad it is that as humans, we now regard all animals with an initial bit of alarm and suspicion, you know? And it seems to be the curse of our species to have that, with our recklessness.

GZZ I guess this sense of threat comes with a kind of respect as well.

AY I think it’s respectful on my end. I think that humans are really extremely vulnerable on the planet – it’s almost like we’re not really supposed to be here. This coexistence with these other animals that carry, you know, ticks that are potentially lethal to humans, it just reinforces for me how robust animal life is, and how fragile and vulnerable humans are. And we’re all kind of entangled in that zoonotic spillover, right?

GZZ Right, I’m kind of taken by this idea that a biosphere is an expression of a planet. I guess humans are part of that too.

AY Yeah, I guess I’m not too attached to [she makes air quotes] “survival”. I think that we had a good run and that, you know, we should maybe just conform to evolutionary processes. That being said, artificial intelligence and the extension of life is part of our evolution as well. It’s not outside of our evolution, and neither are machines.

GZZ That’s an interesting way to put it, you think we’re an ending phase?

AY I was being cheeky about how we had a good run, but I mean, I just don’t think we need to save ourselves at all costs… to what end, you know? At the peril of all these other planetary entities and concerns?I’m okay if the species isn’t propagated, but it’s hard because as biological entities that is part of our drive, right? At the same time, we’re also introducing new species into the world, we are designing life and coexisting with new life that wasn’t there before.

GZZ Has your relationship to science and technology changed over the course of your collaborative projects?

AY My relationship to science and technology is becoming looser and looser, and less about knowledge production. I think art ought to be far more than that, and can be a lot more akin to something like some of the functions of quantum mechanics, if we let go instead of trying to steer it into some knowledge-production territory of certainty, to almost mirror scientific research or the way that science articulates the phenomenon. My job is not to articulate the phenomenon of art. I’m more interested in opening up these nonconceptual spaces. And that’s something that science and technology doesn’t purport to do.

GZZ Can you say more about this nonconceptual space?

AY I guess what I’m trying to say is that I’m trying to be much more open to an absolute reality, versus the relative reality we concern ourselves with through culture. And that is the value of science for me, in that it can tell me about something beyond my own relative reality. Even though I may not perceive things in a certain way, I know that if I were to die, tomorrow, the sun will still come up in the morning, with or without me, and that there will be rain, there will be weather patterns with or without my experience of that reality. Another way of looking at it is really just to reposition, or maybe even de-position a certain kind of certainty.

GZZ Right, a space outside your own relative way of knowing, and beyond the powerfully relative world of “culture”.

AY I’m very, very squeamish with culture. Culture seems like it’s really fundamental to who we are as social beings. However, culture can really perpetuate the worst aspects of humanity and it also can perpetuate all of the falsehoods of humanity. You know, patriotism, nationalism, racism, sexism. It’s all story and narrative. I guess they say that humans need stories [laughs]. But I think that these stories perpetuate a lot of suffering and a lot of obstacles to our growth and evolution.

GZZ That’s an interesting place for art to begin, against knowledge and culture. How do you approach this absolute, transcendental world in your practice?

AY This is kind of an evolving way of thinking with the practice. If we could create a kind of timeline, I think in the last five, seven years, I’ve been thinking about how there is no autonomous, sovereign self, right? And if you look microbiologically, you know that there is no individual and that the self is comprised of a multitude. And so what that means is that the self is – we are – vessels for interdependence. So the work I’ve been exploring has really been thinking about the entanglements of this co-constitutive life, and also just not having this over-reliance [on the distinction] between life and death. Because if ultimately there’s only energy, then the difference between the living and the non-living is pretty insubstantial.

So a great example of that is a virus. I mean, technically, it can’t reproduce. Technically, it would not qualify as living. And yet, it is responsible for regulating all biodiversity on the planet. So we have to constantly update these scientific concepts with new meanings, and this certainty starts to collapse. One of the great lessons that I take from science is that you probably shouldn’t be too attached to any certainty. Because every generation comes around and says, “well, we need to update this idea of what the human is, and we need to update this idea of what climate is.” And so the larger meta-project is maybe that, as an artist, attachment to knowledge production is becoming more of a hindrance than an asset.

GZZ Has this changed your relationship to your work?

AY I’m trying to have a different relationship to the practice. I think that in order for real re-genesis to take place, you have to force yourself to rest. I have never been good at doing that. It was just like: pile on 20 projects and keep going. And I just think I burned through too much energy. And I guess now I have new goals towards having more of a whole-body balance, rather than just being this disembodied, cerebral will, where you’re just like, “No, we can do it, we can do it if I think it!” It does catch up with you, and you can pay attention, or you can ignore it. I can’t really speak for anyone else, but for me, I’ve learned a lot from this pandemic.

GZZ The process of reorientation you’re talking about is tremendously difficult, with the history we’ve inherited. How are you finding it?

AY Yes, absolutely. I find it really pretty blissful and challenging. It’s this different sort of quantum engagement through the body, and how it can lead the mind. I find it really stimulating, but not in the way that I used to get stimulated reading George Church’s books and discovering his theories or something like that. It’s this kind of immersive, totalising way of learning rather than this siloing of knowledge, of experience, of reality. I don’t know, I’m not an expert, I’m just starting out on [laughs] waking up to this path.

GZZ You’ve mentioned quantum a few times, in a figurative way, in describing this process. What do you mean by that?

AY I’m not an expert on quantum physics, but you know, I read a lot about it. So it’s not just figurative, it’s quite literal, in the way that I think my practice can sort of parallel the way that quantum physics can teach us about how the mechanics of the world works. And it also speaks to the history of consciousness, and I’m not sure that there is an ultimate sort of primacy here, but I’m kind of doing my due diligence, you know, in trying to live by the phenomenon [laughs]. Whether it’s microbiology, synthetic biology, quantum physics, these are the phenomena that shape our understanding of the world and ourselves and others. And so, without knowing that, it’s hard for me to try to live the phenomenon. But I would definitely save the phenomenon over the theory any day of the week.

GZZ I really appreciate your interest in reality, in all the fuzziness and non-fixity of that pursuit.

AY Yeah. I mean, one of my goals is to appreciate just existing in the way that birds get to appreciate existing, in the way that plants get to exist without having any value judgement, and without having to produce my own subjectivity or consciousness or anything. I want to exist, and I want to appreciate that I can exist. That’s the goal.

Anicka Yi’s Hyundai Commission is on show at Tate Modern, London from 12 October to 16 January.