What is this most sensitive of artists picking up beneath the placid surfaces of his homeland?

In the simplest of terms, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s tenth feature film is about being alert. Not thinking about the world around you so much as feeling it sharply, being keenly and indiscriminately present, after an awakening of some kind. At least, that’s my interpretation after seeing Memoria (2021) in Bangkok, amid a flurry of Weerasethakul gallery shows.

A brief synopsis: Tilda Swinton’s Jessica, a Scottish flower-seller visiting her sister in Bogotá, Colombia, is woken by a loud, jolting bang. Initially she blames early morning construction work, but when it returns with equal intensity, she realises the sound is interior… hers alone. At a meeting with a sound engineer she tries to recreate it in the forensic manner of a sketch artist: “It’s like a rumble from the core of the earth,” she says as he tweaks a dial on his mixing desk. Later this search leads her into the mountains, where her anguish in the face of this strange presentiment – a sign of madness? A gift of sublime truth? A cosmic roar reverberating through deep time? – turns to fascination. She becomes so keyed into the sonic boom that, in a hypnotic scene towards the film’s final act, she leans sideways by a stream to get closer to it.

As is customary for the mild-mannered Thai auteur, Memoria – a Husserlian pilgrimage that draws its enigmatic plotline from his own experience of ‘exploding head syndrome’ (a bona fide sleep disorder) – abounds with metaphysical resonances and metempsychotic suggestion. There is an all-pervading yet unsettled sense that Jessica has, as she handles prehistoric skulls, talks to lost souls who remember everything and is barraged by the sound over dinner, stumbled upon a portal into Colombia’s past lives, or somehow slipped between bodies. But when I watched Memoria, Weerasethakul’s first foreign-made film, in late February, Jessica’s awareness and interconnectedness in that moment when she leans into the earth also felt important – like a clear through-line to his recent work back on Thai terra firma.

Last October Weerasethakul claimed to be experiencing a similar state of heightened lucidity in his homeland. The stance voiced publicly in 2015 – no more moviemaking in Thailand due to state censorship and the military-proxy government – had not changed, but his outlook had softened. “I don’t know about feature films here, but in terms of short films and different kind of expression, I feel very motivated,” he told me. What had activated him was a Thai explosion: the youth-led protest movement that shook the establishment in 2020 and 2021 with its strident and satire-inflected calls for far-reaching reforms that would, if enacted, stretch to the gilded pinnacle of society. Meanwhile, working in Colombia – a country that shares a ‘heavy history’ of cyclical political strife and asymmetric Communist war – had reminded him that Thailand is not unique, that flawed democracies are commonplace and utopias nowhere. “So you just need to focus on the beauty and gratefulness of everyday life,” he concluded before calling himself out. “It sounds very cliché.”

He was right to call himself out. But the fruits of Weerasethakul leaning anew into his local environment have hardly felt maudlin. In fact, A Minor History – the two-part exhibition at Bangkok’s 100 Tonson Foundation resulting from his roadtrip around the country’s northeast, Isaan, between pandemic lockdowns – surely ranks among the most abrasive and forthright chapters of his celebrated trenchwork: his dogged negotiation of Thailand’s psychogeography.

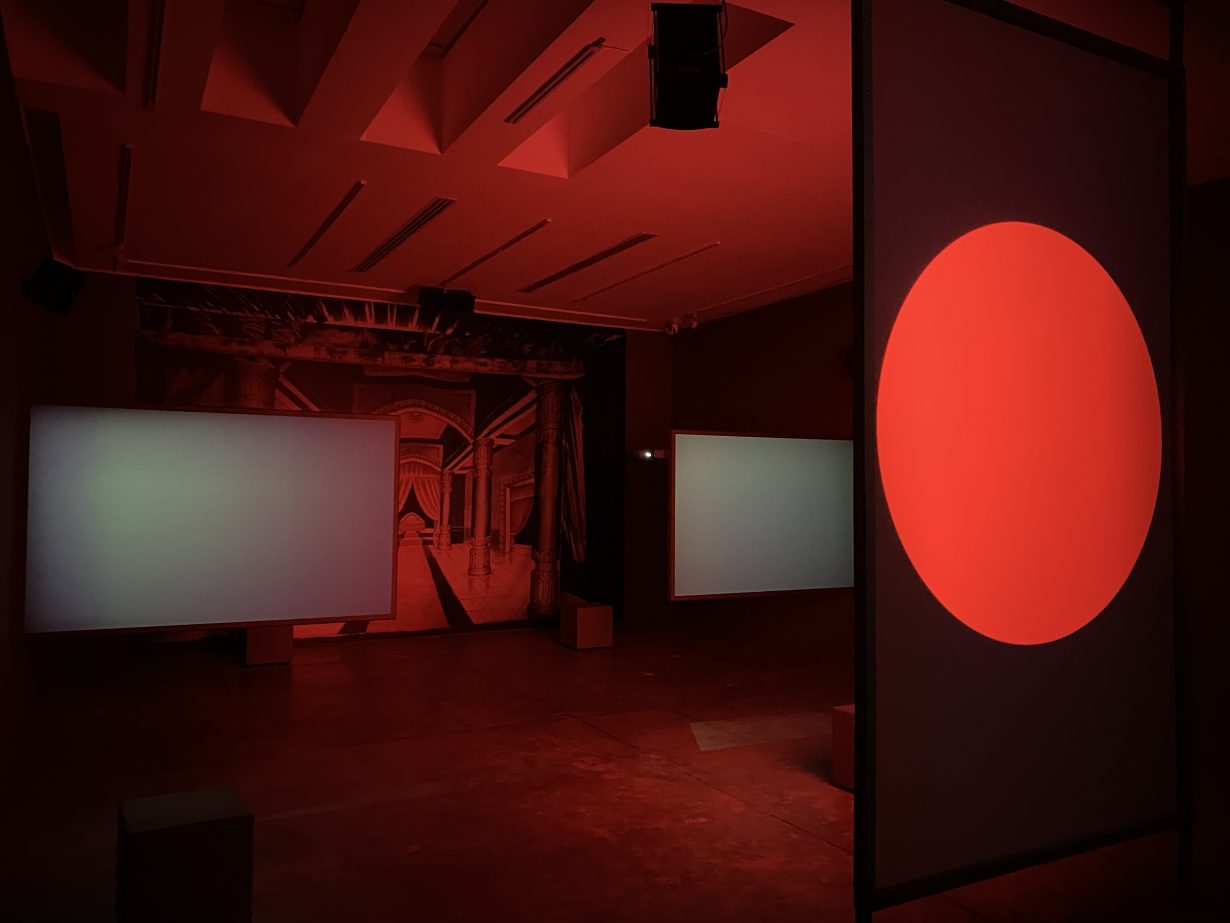

Part one of A Minor History was a Weerasethakul gallery show through and through – an immersive audiovisual experience – albeit one notable for its heralding a new collaboration with a pugnacious poet-activist, and its invocation of an extremely ‘heavy’ news story: the discovery of two murdered Thai anti-establishment dissidents in the Mekong River in December 2018. In the foyer, pictures of Asia’s third longest river were displayed upside down, while footage captured on his roadtrip formed the basis of a three-channel video installation in the main gallery. Scrolling slowly upwards on a double-sided vertical screen in the centre were elegiac shots of nocturnal Isaan: the moonlit Mekong, a neon wheel turning at a temple fair, a woman silhouetted against bedroom curtains, a microphone in a radio studio. This screen partially obscured two larger opposing screens further back, upon which flashed static shots of a crumbling cinema in the region’s Kalasin province.

Orientating us was not the image, however, but sound. A loud thud – resembling the sound of something or someone being struck with a blunt object – was followed by the flapping of startled pigeons. And then a deep male voice began to speak. “Its stomach was turbulent because it had swallowed a drifting corpse,” he began. “It couldn’t digest the body because the corpse was full of concrete. A dead body was stashed in a concrete mould, bundled up in ropes, metal chains and wires.” Young Isaan rebel poet Mek Krung Fah was narrating a tale of the northeast’s mythical naga serpent. And it was struggling, coughing up legs, arms, feet, a cock, organs, as a man and woman strolling along the Mekong looked on with a mixture of fascination and horror.

Towards the end of the 17-minute piece, imagery and storytelling gave way to three channels of running white-on-black text. As it scrolled right to left in large Thai and English font, and to the sound of slowly grinding metal, these snippets of prose drawn from Weerasethakul’s diaries and roadtrip interviews evoked the stream of consciousness besetting a scattered nervous system – or an insomniac, perhaps, as they lie blinking in the dark. Snippets of fraught conversations flashed forth: “My dad said if you weren’t my daughter, I would have shot you”.

During opening week, Weerasethakul stressed that this impressionistic piece was, on one level, an elegiac farewell to saak (remnants, carcasses) or bygone expressions – spiritual, ecological, architectural, artistic, textual – in the region where he grew up. The pulpy backdrop of a royal throne hall on the back wall, in which pillars frame a red carpet, is the kind used by mor lam theatre troupes. The playful dramatic style, wherein the narrator gamely voices all characters, belongs to obsolete old-school radio dramas and cinema dubbing. The images of the cinema evoke his childhood memories of being enthralled by 16mm Thai dramas and Steven Spielberg spectacles. And the footage of the Mekong is a continuation of his decade-long interest in documenting its changes, particularly in light of the Chinese dams now upstream.

Yet the main loss A Minor History chronicled was the disappearance of minor characters, the real-life erasure of antimonarchist activists who, having had their hands bound and bodies stuffed with concrete by kidnappers who remain at large, are now no more than ghosts “vanished into the void”. But who, the exhibition hinted, also possessed a seismic potential that could, potentially, cause the world to shift. “Was it playing?” asks a high-pitched Mek Krung Fah near the end, performing the role of the woman as she expresses concern about the naga’s condition. “No, it was dying,” replies the man. The potent symbolism of this image was only compounded by concurrent interviews, in which Weerasethakul compared Thailand’s current regime to a floundering animal in its death throes, wreaking havoc all around it.

Then, in early October, 100 Tonson Foundation temporarily gave itself over to a work that, to paraphrase one of A Minor History, Part I’s ironic self-reflexive moments, felt like another ‘tiny ant-sized story’. Commissioned by the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, Silence (2021) commemorated an even rawer festering Thai wound: the 6 October 1976 massacre, when 40 leftist students at the capital’s Thammasat University were killed by rightwing paramilitaries and bystanders.

In this iteration of the minimal 21-minute installation, which screened for five days to mark the event’s 45th anniversary, images of bloodied corpses, frozen in grimaces of pain, faced off with clips of mass distraction, from Bangkokers at leisure, to Payut Ngaokrachang’s cartoons, to footage from the nationalist epic The King of the White Elephant (1940). And streaked throughout, like blood flecked across a smashed face, were lines of Weerasethakul’s poetry that implied society at large had tuned out, been decapacitated by sweet, lulling dreams in which ‘speeches sound like music’, gunshots like ‘mysterious fireworks’ and curse words like chords (‘Asshole: C Minor 6’). ‘National Sleep Week’, he calls it. For anyone familiar with Weerasethakul’s work – a practice known for its placid realist-mystical veneer, multivalence and subliminal politics – it was as if a planet had eclipsed the sun, thrown his obstruse world into hard-edged darkness. Pain, regret and anger scorched everything. This impression was only reinforced by the implacable live-performance element of A Minor History. During Galleries Night weekend in late November, crowds headed up to 100 Tonson Foundation’s roof to watch Mek Krung Fah give a poetry recital that did not mince words.

In ten years, if you are still alive

Let me offer you shame and disgust!

That today you pretended not to hear

The voices of your slaughtered countrymen

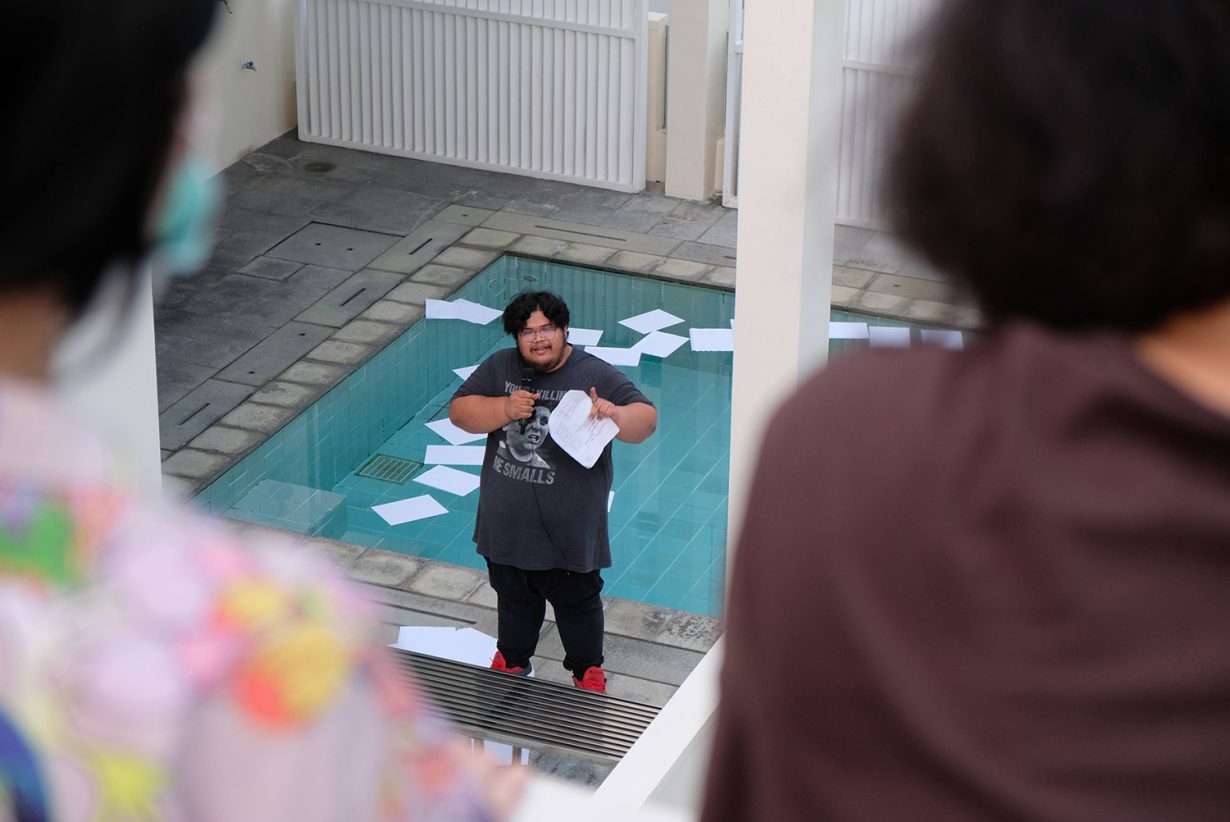

As quatrains of this fiery nature rang out in Thai over a speaker system, Teerawat ‘Ka-Ge’ Mulvilai – a performance artist and founder of the city’s B-Floor theatre troupe – ambled around a swimming pool on the floor below. Midriff bared, and donning a white mask, he slowly laid English printouts of Mek Krung Fah’s Unsubjected Verses (2021) around the edge.

A few weeks later, Weerasethakul’s video documentation of this performance showed up in yet another exhibition, A Trace of Thunder, at Maielie gallery in Khon Kaen, the city in Isaan where he grew up, the son of doctors. While it is joined by photographs that further his fascination with light in all its forms, the show’s key element is text. In the role of art director, Weerasethakul has turned excerpts of Mek Krung Fah’s ire-filled words into concrete poetry. They run down a hanging banner in oversize Thai font and, in a room where two chairs sit on wooden pallets flanked by LED spotlights, loop across the floors and ceiling in unbroken bolts. Here, amid his own injunctions to ‘stop crawling’ and ‘fight for the truth’ – some of them so subversive that the Thai words were deliberately misspelled to avoid authoritarian rebuke – Mek Krung Fah has been staging his counterreaction radio show. (Topics discussed include, among other hot-button topics, the government’s widely contested plan to tighten regulations for NGOs.) The implication of this broadcast-room installation is clear: the rousing oratory and critical debate of Mek Krung Fah and his ilk wield an electricity that can give us a transformative jolt. Like a trace of thunder coursing through the walls and floors of a building. Or as the lightbox images of digitally rendered explosions on the far wall imply (Mr Electrico (For Ray Bradbury), 2014), a neural explosion in the recesses of the brain.

Over the last decade or so, Weerasethakul, now fifty-one, has often employed nonprofessional actors as discreet vessels for the nation’s psyche. In a body of work in which violence feels barely suppressed – from shorts such as Fireworks (Archive) (2014) and Vapour (2015) through to his last Thailand-set feature, Cemetery of Splendour (2015) – their presence conjures a state of mind under Thailand’s political conditions, or gestures towards collective scars. This cluster of exhibitions, however, possesses a markedly more instructive and belligerent tone than these more elusive precursors. And not simply because that’s what happens when you team up with sympatico Thai performers, poets and artists with starkly different working methods and modes of expression. One senses that Weerasethakul believes the situation calls for it.

Which is not to say that his powers of abstraction and subtraction, nor his ability to imbue matters of politics and history with an intoxicating sense of mystery and ambiguity, have been diminished. Part two of A Minor History, titled Beautiful Things, is a case in point: at once subtle and searing, uplifting and destructive, minimal and expansive.

The six photographic works lining the walls – again based on images taken on his roadtrip – are palimpsests representing the confusion, torpor and amnesia of local Thai reality. In one image, text floating over a river landscape seems to announce a movie double-bill: Mekong Murder Mystery vs Dreams and Delusions. Others super-impose Weerasethakul’s own photographs of Bangkok’s recent street protests over shots of peri-urban decay, or rooms where light spills from windows onto unmade beds (windows are another Weerasethakul leitmotif).

Meanwhile, the inclusion of two works by young male artists from Chiang Mai strike a more sanguine tone. Suggestively obscuring the regal mor lam theatre backdrop on the back wall is Natanon Senjit’s painting Break Out of the Loop of National Conflict into Peaceful Nature: a faux-naif paradisical landscape in which members of Thailand’s pro-democracy protest movement and their allies appear defiant, if slightly cutesy. And making a guest appearance in 100 Tonson Foundation’s office-cum-annex is someone unexpected, even for Weerasethakul’s spectrally attuned body of work: a sacred lotus flower deity with four eyes, two phalluses and a bulbous head dotted with mirrored glass. According to curator Manuporn Luengaram, this sinuous red sculpture – an icon by the artist Methagod representing the resilience of the lotus flower – stands as a reminder of ‘the perpetual resurrection of Thailand’s youth movements despite being time and time again suppressed.’

And then there’s the ominous video component. While part one of A Minor History deployed a thud sound to evoke collective memories – much in the same way that Memoria does with its cinema-rattling bang – part two’s single-channel screen creeps along silently. Travelling slowly up the jet-black vertical screen is oversize Thai text, a trail of free-associative thought bubbles drifting into the ether. Punctuated by large spheres resembling fullstops, these flecks of distilled memory touch on, among other things, the meth trade (‘Soldiers distribute meth | Sell and resell | up the hills to Tais’), the temple murals of nineteenth-century painter Khrua In-Khong (‘Khrua In-Khong | utilised the skyline | and vanishing point | filling in shadows and darkness along the tree trunks’) and the teachings of the late Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (‘I prefer looking | at nature | more than | looking at any picture | in any museum’).

Some of these diaristic snippets clearly allude to throwaway thoughts or wider social truths; others appear to gesture towards formal qualities of the exhibition. Krua In-Khong, for example, was an innovator who introduced perspective, shadow and shade to the flat Thai temple mural. Similarly, the images presented here toy with our field of vision and vanishing points to get us ‘closer to reality’ – a reality full of distortions.

But the most illustrative allusion, for me at least, is the veiled reference to the zen wisdom of Krishnamurti, whose meditation teachings and interior journey Weerasethakul has been pondering of late. And who tried to approach everything, from perceptions to consciousness, from conflicts to mountains, with a uniform and deeply perfected sense of quotidian wonder.

Channelling Weerasethakul’s sensitivity to every plane of existence, the components of A Minor History have sought to find a similar measure of beauty – and egalitarian zen spirit – in the simple act of being keenly and indiscriminately present at a pivotal moment in Thai history. A moment when the loud rumbles of dissent have been stilled, when some protest leaders are facing charges of sedition and when a political awakening that made headlines around the world is being methodically relegated to ‘tiny ant-sized story’ status. For him, appreciating the fullness of this forest, being alert in the presence of murder mysteries, unfettered thoughts and those who dare speak truth to power, is no mere one-off gesture of solidarity or resistance. As he puts it, “It’s about surviving here, what it takes and recording memories.”

A Minor History, Part ii: Beautiful Things is on view at 100 Tonson Foundation, Bangkok, until 10 April