Ana Prada’s work is, quite literally, off the wall. After two decades of producing labour-intensive wall works – in which the work is manufactured during the installation process, often involving multiple tacks or staples – her production has recently diversified to include freestanding sculptures, photomontages and graphics, which radically extend the complexity and narrative scope of her oeuvre, while at the same time elucidating and augmenting its reading.

Most critical texts on the Spanish-born, London-based artist place her in the context of Minimalism, but the repetition of basic units aside, the artist has little in common with the predominantly male ethos of the 1960s movement. Unlike the sculpture of, say, Donald Judd or Carl Andre, Prada rarely respects the integrity of the readymade but rather deconstructs the everyday objects that form the DNA of her work to the point where they pass almost beyond recognition. Small, mass-produced objects such as plastic clothes-pegs, false nails, hair curlers, combs, tights, teabags or electric wires, not to mention more substantial items such as mortars and pestles, are dissected with an almost surgical precision, before being assembled in geometric or organic formats as wall or floor sculpture. This is approached with the exactitude of Crick and Watson’s pursuit of the double helix, yet reveals a regard for an aesthetic that is closer to the Oriental tradition than the values of the materially-orientated West. The very fact that dismounting an exhibition essentially destroys much of the work places it more on a conceptual footing, yet that is again to deny the purely visual delight the artist weaves around the commonplace.

Prada’s work is like a detective novel, full of false leads that frustrate our initial reading and demand closer inspection. Depicting robust yet surreally deformed objects, the ragged lines in her graphic works initially hint at the grain in Japanese woodcuts, but in fact largely originate in fragments culled from commercial illustrations and comics. These Robert Crumb-like images have been photographed, rescaled and computer-manipulated, before being retouched by hand on the final printout.

Similarly, when an oversize bubblegum ‘balloon’ seemingly adheres to the gallery floor, all is not what it seems: the bubble is simultaneously present and absent, the voluminous pink mass a photomontage of an actual gum bubble mapped onto a photograph of the empty gallery space in which we are standing. By setting the fantasy within the real space inhabited by the viewer, we are invited to do a double take, a device akin to the ambiguous reflection of ourselves as the royal couple in Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656).

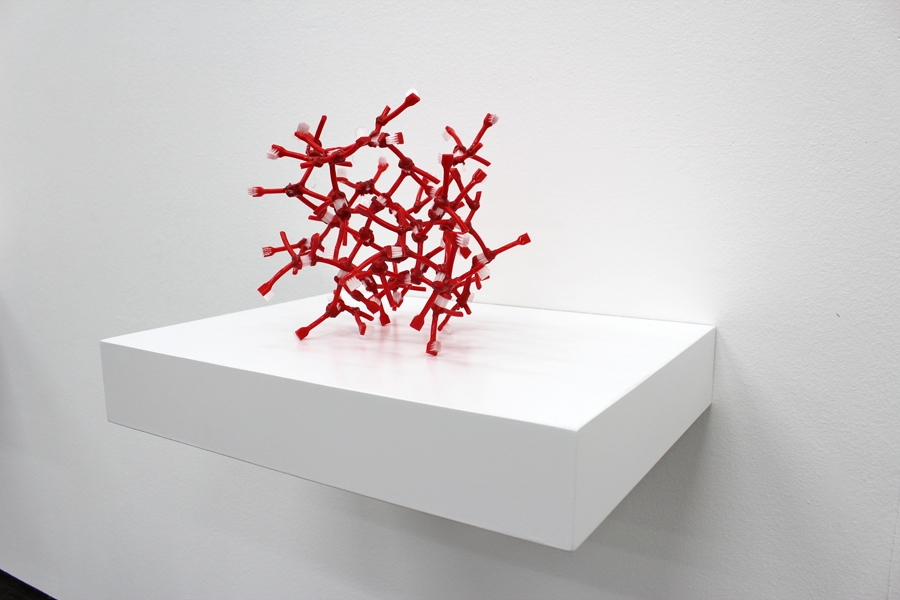

As an earlier catalogue essay remarks, Prada’s work elicits comparisons to Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass (1871). Prada’s is a world of surprising inversions, where nothing is quite what it seems and the mundane reality of the everyday is transformed into an aesthetic wonderland: such as the electric-toothbrush heads in the T.B Creator series (2015) that, released from their familiar context, combine and multiply to evoke a subatomic microcosm or crystalline growth. As the artist herself says, the work is essentially about realising the visual potential of the commonplace. And as Crick and Watson claimed of the double helix, the discovery of its structure was only made possible by the a priori conviction that the answer to their quest would be both simple and beautiful – despite the complexities of their discovery that continue to unfold with the passage of time.

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.