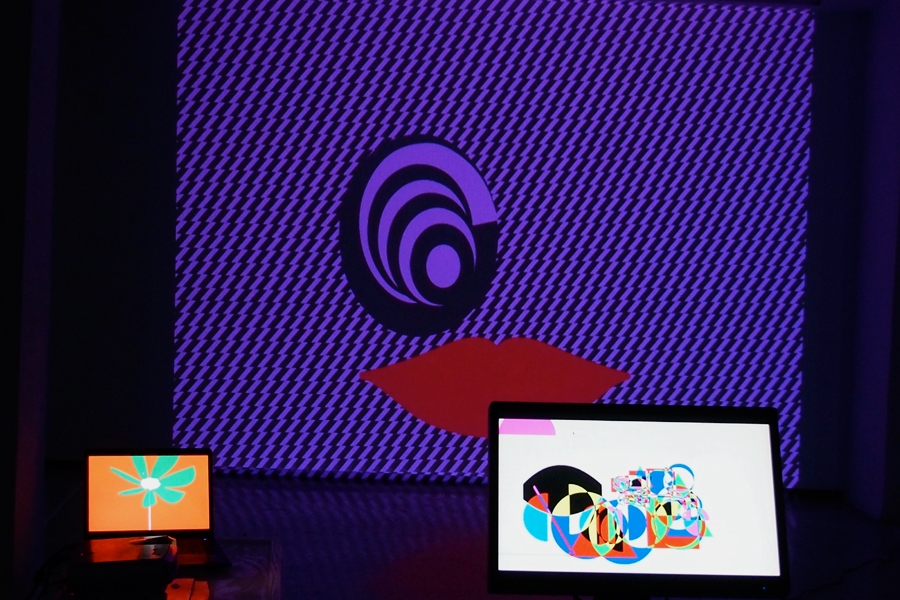

On the Internet one can find an ignorant creature with a strange beak that is compelled to chase the cursor on the web page, while walking in an endless landscape that is reminiscent of the reconstruction of a mescaline trip. This artwork by Angelo Plessas is titled after its URL: MetaphorsOfInfinity.com (2012). Installed at the Breeder gallery, it is part of Plessas’s solo show, Mirage Machines, together with several other websites realised by the Greek-Italian artist. In the darkened space, a few computers and as many beamers rest on the floor or on some plastic boxes. Kept functioning by a tangle of cables, they cast on the walls a disorderly display of projections, creating an otherworldly atmosphere worthy of a digital temple. Images on the walls feature an explosion of coloured balls (BeforeEverything.com, 2014) and a big spinning flower that changes colour and shape at every click (BonjourTristesse.com, 2014). In the basement of the gallery, the setup is similar but things get more obscure, with mysterious diagrams inscribed into planets that produce randomised piano notes (OnceInAThousandYears. com, 2010) and lifeless mannequins that we can toss onto pyramidlike constructions (SymmetryOfChaos.com, 2009).

These pieces of software are populated by curious inventions and weird critters that inspire a playful techno-animist sentiment when poked or disturbed with a click of the mouse. Confronted by the electronic autism – the restriction and repetitiveness that comes with experiencing Plessas’s automata – would it be legitimate to wonder whether the increased intensity of connections between humans makes machines more intelligent, or whether it is the other way around? The same applies to a number of deadpan faces, which are possible to identify in a series of abstract shapes that we instinctively recognise as eyes, noses and mouths. The face is a recurring theme for Plessas, who often indulges in the solaces of electronic portraiture – where the avatar is the symbolic attempt to transcend into a virtual ‘someone else’. What comes after is the ambiguous interfacial relationship with an entity that looks in our direction from the other side of the screen: is the screen itself a quasi-face that we address most of the time, or are avatars an expansion of subjectivities into an endless series of digital multiples?

In his seminal book Expanded Cinema (1970), Gene Youngblood argued that the art of the so-called ‘new media’ was taking a step towards the development of a new consciousness. ‘It is the belief of those who work in cybernetic art that the computer is the tool that someday will erase the division between what we feel and what we see.’ Youngblood believed that the computer would evolve into an aesthetic machine or, in other words, a means to achieve a new consciousness for a new cybernetic environment. While interacting with Plessas’s websites, we are encouraged to perform basic gestures for the exploration of this environment. A whole choreography of tactile investigations is created with simple tools such as a mouse and a screen. Swiping, dragging and dropping seem to be gestures of an augmented perception through which we learn, we question and we probe. How many colours – an artificially small amount here – do we see when we look at a screen? How do objects fall when gravity is simulated by an algorithm? How does the Internet feel?

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.