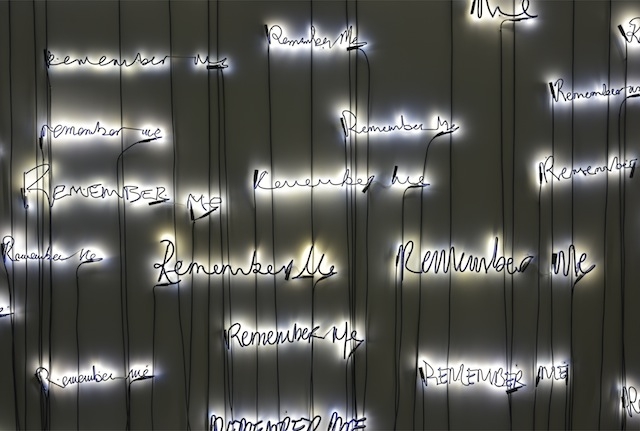

Steve McQueen’s first solo show since 2014 contains only two new works: Moonlit (2016), two silver-painted rocks; and Remember Me (2016), 88 repetitions of the title in white neon. Sculpture is a rare medium for McQueen, and by no means his strongest – I can barely remember the elements of only two previous works, both shown in his ICA show in London in 1999, the year of his Turner Prize. These new ones are scarcely more memorable, at least on first viewing. Moonlit is especially mute, while Remember Me’s repeated phrase, which probably comes from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (1689), specifically, ‘Dido’s Lament’ – ‘Remember me, remember me, but ah! forget my fate’ – only (at first) makes me reflect upon, but not exactly lament, McQueen’s fate: a gallery-based artist whose best-remembered early works include two short films where he wrestled naked (Bear, 1993) and pissed onto the camera lens (Five Easy Pieces, 1995), now a Hollywood A-lister writing, directing and producing a TV series for HBO.

The third piece on the gallery’s main floor, Broken Column (2014), last seen just over a year ago at Thomas Dane Gallery in London, doesn’t move us much, either: two black Zimbabwe granite columns, one brilliantly polished, a little over two metres high and perched on a wooden pallet; the other, identical but a quarter the size, caked in clay and housed in a Perspex box on a white plinth. The columns appear to riff off similarly named works by Frida Kahlo and Barnett Newman, perhaps, or pay funerary homage to the lives and lands destroyed by granite mining in Zimbabwe.

Three works that leave us cold. So on we go, down the stairs, past another element from the Thomas Dane show, a stack of double-sided posters, with, on one side, a grainy image of a bareback young black man in white shorts sitting on the bow of an orange boat at sea; and on the flip side, the same image covered with white text about a man’s murder. Reaching the basement, we see still one more element from the earlier show: the same man on the same boat, now a moving image projected on a standalone screen in the centre of the room. He is facing the camera, smiling, mugging a little, happy to be the focus of our attention. The endless horizon bobs up and down in the background, waves slap the hull and a voice, in thick Caribbean patois, says the words transcribed on the poster: “They shoot him in the back and when he fell one of them guys went over to him and shoot him up around his belly and his legs and thing. And that was about it…” We hear, too, incongruent scraping and banging, metal on stone.

Circling the screen, we see projected on the other side another moving image, in both senses: men in a cemetery constructing the young man’s tomb. McQueen shot the boat footage in Grenada in 2002, six years before his Caméra d’Or at Cannes, 12 years before his Oscar, and two months before the young man’s murder and subsequent burial in an un- marked grave. McQueen learned of the man’s fate – shot and killed over a drug stash – in 2009. Four years later he resurrected the boat footage, added the voiceover, titled the work with the man’s name, Ashes (2014), and showed it in Japan and London. Last year, he disinterred Ashes’s body, gave him a proper burial and premiered the double-sided projection of him (Ashes, 2002–15), alive and in death, at the 56th Venice Biennale.

From potter’s field to Paris gallery, Ashes to Ashes and dust to dust. We climb back out of the ground, up the stairs, back past Remember Me, Ashes now haunts the room. Dido’s lament elicits an electric chill. Moonlit is gloomed in melancholy. Broken Column radiates mourning and loss. My dismissive disdain leaves a bad taste, all my trust and travail is but waste. Life is short, and shortly it will end, and McQueen’s memento mori will outlive us all.

Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris 9 January – 27 February 2016

Read our Power 100 profile of Steve McQueen here.

Our 2014 review of his solo exhibition Ashes can be read here.

This article first appeared in the April 2016 issue of ArtReview