From 2017: The Paris-based Turkish artist’s works on politics, feminism and migration are as relevant now as they were 50 years ago

The relationship between people and places, and the assumptions made about both, underpins the dominant discourses of contemporary politics worldwide. Examples are myriad, from the seemingly endless refugee crises in Europe and elsewhere, to the more loudmouthed mythological articulations of Trumpists, Brexiteers, followers of Hindutva and various other forms of nationalism, all of which seek to articulate who does and doesn’t belong within the defining lines of various accidents of cartography on our planet. We live in an age – as have so many others in earlier times – in which the primary function of much political rhetoric is to justify degrees of exclusion and repression.

The relationship between people and places is also the dominant discourse in the work produced by Paris-based Turkish artist Nil Yalter over the course of her more-than-50-year career. It’s no secret that interest in Yalter’s work, often not particularly evident at the time in which she made it, has been increasing over the past seven years. During that time, while Yalter’s production of new work has slowed (it’s harder to maintain the energy, she complains, when we meet in what she calls her Paris ‘computer studio’), her existing output has been included in biennials in Istanbul and Gwangju, and a part of her Temporary Dwellings series (1974–77), for example, now hangs front and centre in Tate Modern’s new extension. In a manner typical of the delayed fashion in which much art and cultural intellectualism operates – and by no means am I excluding this magazine from that – this septuagenarian artist’s past has come to symbolise our present. But that’s not to say that looking at Yalter’s work is merely another opportunity for a critic to analyse today from the relatively safe vantage point of yesterday.

Migration has, in many ways, defined her life as much as it has her art. Born in Cairo to Turkish parents, Yalter moved to Istanbul at the age of four. With no formal art training, she is “in everything” an autodidact, she says; her earliest works, from the late 1960s, took the form of abstract paintings inspired by the Paris-based Russian painter Serge Poliakoff, as well as some performance and costume design. Although she exhibited regularly in Istanbul at the beginning of her career, in a 2013 interview with curator Adriano Pedrosa she reflects on how, at that time, it was a city that had not engaged in contemporary culture, let alone contemporary art: ‘in 1958 there was nothing, not a single gallery, no museums, no books, nothing… we didn’t do anything contemporary in Turkey in those days’. As a result, Yalter decided to move from European art’s periphery to its centre, making Paris her home in 1965. This was a transition revisited in Orient Express (1976), comprising Polaroids, drawings, text and a film shot during the artist’s ride on one of the storied train’s last journeys from Istanbul to Paris. The work quietly highlights, via observations of fellow passengers and passing landscape, the route’s glamorous aura, the mundane realities of travel, the human emotions associated with leaving one place for another.

In Paris, Yalter came into contact with Pop and conceptual art, encountering artists such as Robert Morris and Bruce Nauman, and by the early 1970s she was pioneering the use of installation and video, before later continuing her experiments with media outside of the established art-historical canon by engaging with computer programming during the early 1990s. But it is the work made in between these two periods for which she is now best known. Temporary Dwellings found its definitive form – 12 panels, seven of them now in Tate’s collection, comprising photographs, objects, drawings and text, alongside video interviews with Turkish immigrants conducted in 1978 – at an exhibition in Vienna’s Hubert Winter Gallery in 2011. Taken together, its aspects document the interlinked lives and living conditions of largely immigrant communities in Paris, New York and Istanbul; they’re dated and located as studies of, among others, Portuguese and French workers in Noisy-le-Grand in Paris’s eastern suburbs, and Puerto Ricans chased out of and now reoccupying buildings on New York’s Amsterdam Avenue. Each panel contains two rows of Polaroid photographs – some annotated with baldly factual descriptions, others not – documenting aspects of the location, interspersed by two rows of drawings and objects found onsite: fragments of wall and floor materials, notes from an English lesson and other detritus. The end result is a portrait of people whose presence is at once evident and absent: the very essence of an indeterminate existence.

As much as the panels of Temporary Dwellings utilise a documentary or ethnographic form to highlight a certain poverty of life – as do several of Yalter’s other works – they also mimic the ‘they’re here, but shouldn’t be here’ formula that defines much anti-immigration rhetoric, revealing something of its logical absurdities. A similar technique is at play in a 1974 collaboration with fellow artist Judy Blum, Paris Ville Lumière, in which the artists documented key sites in the city’s 20 districts, producing for each a collection of text, drawings and photographs drawn, written and printed onto cloth. The 2nd arrondissement, for example, features the stock market: ‘women were not allowed into the stock market at the time. They didn’t even notice that we were women when we went in,’ Yalter recalls.

And of course, Yalter’s is not exactly a Romantic tale of one woman’s voyage from backwaters to the cutting edge of contemporary art. Gender plays a role in this too. In the same interview with Pedrosa, she recalls the celebrated French gallerist Yvon Lambert telling her ‘that he would never show a woman artist, because you never know what she would do, she could fall in love, go to Australia with a man, make a child’. An art market that works like the stock market: plus ça change. In 1975 Yalter cofounded the group Femmes en Lutte (Fighting Women); 32 years later, in 2007, her work was included in Connie Butler’s landmark exhibition WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at MOCA Los Angeles. So maybe some things do change, if slowly.

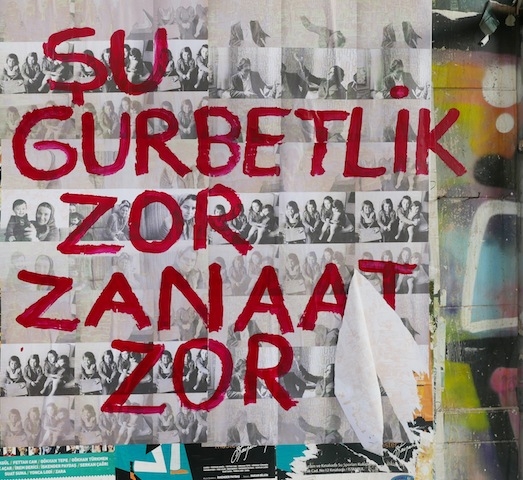

Yet Yalter’s work is not only relevant because it highlights a nexus of political, economic, feminist and migrant issues that remain current today, but for how it exemplifies the unique capacity that art has to address such issues. Not just the easy way – by bearing witness to suffering – but by interrogating and exposing the fears entrenched on both sides of such debates. Yalter has most recently deployed such tactics in a series of illegal flyposters featuring images of immigrants that appear in previous works, painted over with the slogan ‘Exile is a Hard Job’ (the title of a work originally made by the artist in 1976). To date these have appeared alongside exhibitions of her work in Valencia, Metz, Mumbai, Vienna and Istanbul; Brussels is next. In formal terms, the posters introduce the faces of people a city wants to ignore or exclude into its very urban fabric. Yet they do so in the most fragile of ways; in most cases the paper posters are quickly and violently torn down by residents and passersby. As much as this work bears witness to the suffering of immigrants, then, it exposes the rage and intolerance of the society in which those immigrants find themselves.

Back in her studio in Paris, Yalter, still as tuned-in and passionate as she ever was, is considering her own precarity in the face of both old age and the rise of the political right in France and Turkey. “Maybe I’ll have to go back to Istanbul and wear a veil,” she says wryly. Exile is always a hard job.

Work by Nil Yalter is included in The Absent Museum at Wiels, Brussels, from 20 April through 13 August

First published in the April 2017 issue of ArtReview