‘Stop glamorising violent men! Where the fuck is Ana Mendieta? NEVER FORGET… CARL ANDRE KILLED ANA MENDIETA.’ So read a cardboard placard, decorated with teardrops and a portrait of Andre with a Pinocchio nose, at a protest outside the opening of Tate Modern’s Switch House in 2016.

When Ana Mendieta fell from the window of the apartment she shared with Carl Andre in 1985, in the midst of a drunken argument, her death cleaved the New York art community in two. Many refused to believe that an artist preparing for her first solo institutional show, at the New Museum, had committed suicide; nor did they think it feasible that she might have fallen accidentally. Others accepted Andre’s acquittal in court, believing that the continued accusations of murder were designed to serve a feminist agenda. The unsatisfactory official verdict did little to quell the discord, and the case continues to prove divisive. Judge Alvin Schlesinger, the man responsible for the decision in a bench trial, later admitted that although Andre ‘probably did it’, there were no grounds to rule out reasonable doubt. In the decades since, in place of closure, the couple have become the protagonists in a macabre artworld legend, with Mendieta playing the role of Cuban exile and martyr-on-high and Andre the white male bogeyman.

The protest at Tate Modern was carried out in response to the inclusion of Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966) in the new building’s inaugural display. It was organised by a cohort of artists and activists who have taken up Mendieta’s death as an emblem of the abuse of women, particularly women of colour, and who accuse institutions of condoning this systemic abuse whenever they choose to exhibit work made by Mendieta’s husband and (as they maintain) killer. In an article for Artslant, Liv Wynter, the organiser of the protest – who in March publicly resigned from her role as one of four artists-in-residence with the schools workshop programme at Tate Modern following injudicious comments by director Maria Balshaw about sexual harassment – alluded to the manner in which Mendieta’s story has become a proxy for wider issues. ‘My motive was basically to make noise, to remember our sister who has passed, and to demand acknowledgement for how many murderers and abusers, most of whom are white men, occupy these galleries.’

Murder is not the only offence of which Andre is popularly accused. Some of the charges are more unflattering than illegal, others pertain to the transgressions of his demographic, but all add to the prevailing appetite for retribution: Andre was lauded among the greatest sculptors of his generation at a time when the work of women was routinely absent from museums and galleries. Guilty, of gender privilege. He told the emergency services operator that Mendieta ‘went out the window’ following an argument about his greater fame; a detective later told the writer Robert Katz that, when he arrived at the scene, Andre produced a catalogue of his work to show him. Guilty, of delusions of grandeur. Andre’s defence argued that Mendieta’s ‘fiery Latin temperament’, and her interest in the Afro-Caribbean practice of Santería, was evidence of a suicidal disposition. Guilty, of racial stereotyping. The case against Andre was so hamstrung by police procedural errors as to make prosecution almost impossible. Guilty, of belonging to a group who routinely avoid censure for domestic abuse. Yet found not guilty of second-degree murder.

In New York, 1992, a few hundred people turned up outside the Guggenheim SoHo to protest the exhibition of Andre’s work, among them Mendieta’s friends. It would be over 20 years before the second protest occurred, organised by the artist Christen Clifford and spurred on by the opening of an international touring exhibition of Andre’s work, Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010, that debuted at Dia Art Foundation, New York, 2014. Clifford is too young to have known Mendieta personally, but she feels a close affinity to her work. Over the phone she told me that, as a young woman, she had reenacted some of Mendieta’s Siluetas – outlines of her body, dug out of ice, mud and sand, filled with blood, set on fire, left to dissolve beneath the tide and the sun. Clifford stumbled across a number of articles published in the run-up to the opening at Dia, all of which framed Andre in a positive light. Her thought process went something like this. ‘Wait, isn’t this the guy who killed Ana Mendieta?’ followed by, ‘Why is no one saying anything?’

On a May evening, a small group gathered outside Dia: Chelsea wearing white, forensic-style overalls. Clifford unfurled a banner bearing the words ‘I WISH ANA MENDIETA WAS STILL ALIVE’, and a bag of chicken guts was deposited on the pavement – a reference to Mendieta’s early videowork Moffitt Building Piece (1973), for which she left a pool of blood on the pavement in Iowa City and filmed the reactions of passersby while hidden in the back of a car. The second protest took place the following March, inside Andre’s exhibition at Dia: Beacon. Clifford and a handful of friends staged a cry-in, sobbing by Andre’s sculptures, until they were escorted off the premises by security. Outside they made Siluetas in the snowbanks and embellished them with fake blood.

The protests also proved divisive. ‘When I first heard about the protests in New York, I’ll admit I rolled my eyes in disdain,’ the scholar Jane Blocker wrote in Culture Criticism. ‘The protest at Beacon seemed similarly silly – crocodile tears manufactured for the occasion by people who, judging from the photo documentation of the event, weren’t even alive, let alone grieving, in 1985 when Mendieta died.’ The artist and curator Coco Fusco, who knew Mendieta briefly in life, had a similarly caustic response to Mendieta’s posthumous canonisation. ‘The people who can’t separate her from Carl Andre and from her untimely death’, she wrote to me, ‘are obsessed with constructing female experience as victimisation. They are not concerned with her art or her life, only with capitalising on her death to justify fantasies that are neither empowering nor politically sound.’ (Wynter’s recent resignation from Tate would unlikely alter Fusco’s position. In an email circulated to the press offering herself for interview, Wynter comes uncomfortably close to taking credit for Mendieta’s stature: ‘Within months’ of the protests she organised, she wrote, ‘Ana’s work was being celebrated, leading onto many film screenings and spotlights on her – this happened as a direct response to the two protests.’)

Fusco and Blocker are ardent and intelligent advocates of Mendieta’s work, who acknowledge the likelihood of Andre’s guilt. They are not women whose opinions are easy to dismiss. Blocker ends her essay on a conciliatory note, accepting that the protesters’ tears may well be genuine, yet it occurred to me that both the protesters and their critics were right – a reality typical of the era, in which virtue and self-interest are not easily parsed. The legal system’s ineffectual record of prosecuting domestic violence must be scrutinised, as must the precedent for facilitating abusive men. But to turn a dead woman into a martyr is to turn her story into your own, and to view Mendieta only through the lens of victimhood is to risk repeating her erasure.

I am cautious of the expectation that a protest be perfect because it risks overshadowing the very reason it has mobilised. When conservative estimates suggest 35 percent of women globally have been assaulted by a male partner or ex-partner, it seems unwise to tear down the house because we object to the colour of the walls. A deadly war is being waged against women, in which the legal system has shown itself an ally to the aggressor, and it is in response to these bleak conditions that Wynter and Clifford felt compelled to act. (‘Of course I wish she didn’t have to be a victim,’ Clifford put it. ‘How much better if she were still alive.’) Nevertheless, I felt a growing unease at the repurposing of imagery from Mendieta’s oeuvre as a means of symbolising her victimhood. Moffitt Building Piece – echoed in the dumping of guts outside Dia: Chelsea – shows Mendieta at her most complexly voyeuristic. Passersby are shown blood, but without a body, and with no way of ascertaining cause or effect. To confuse the blood of Mendieta’s work with the blood of her death is to overshadow its particular cosmology of meaning – the metaphysical reckoning with her status as a Cuban exile, the desire to manipulate and overwhelm audiences – which add to its peculiar emotional charge. As Maggie Nelson writes in The Art of Cruelty (2011), ‘You can’t toss it in the ghetto of feminist protest art and ignore its more aggressive, borderline sadistic motivations and effects.’

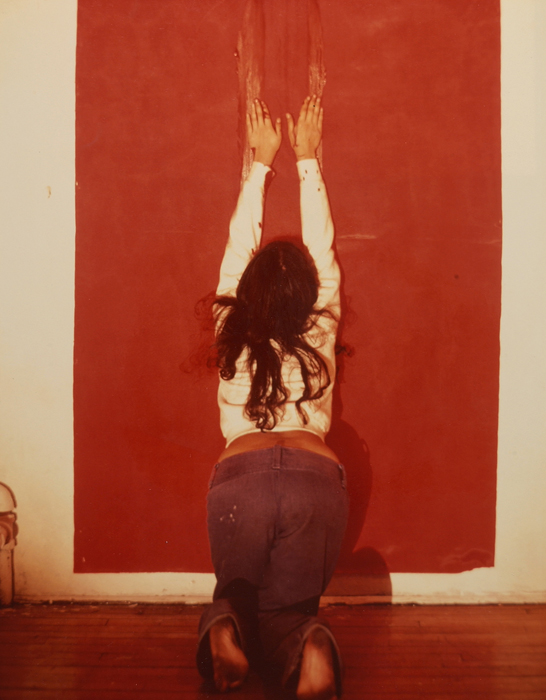

By the time the protests spread to London in 2016, the mood had grown angry, and increasingly morbid. Participants arrived in funeral attire, and later returned with arms dipped in red paint, a reference to Mendieta’s performance Body Tracks, in which she drags her blood-drenched arms down a canvas – again, the blood of her work mingled with the blood of her death. A pamphlet handed out that day contained a piece of writing by the artist Linda Stupart, in which the details of Mendieta’s fatal fall from the window of Andre’s apartment are described in bone-splitting detail. Following the protest, I contacted Stupart to enquire about the resurgent interest in the case. ‘The abject, Cuban, bleeding, traumatised body and her work is literally murdered by Andre and his minimalist utopian yawnfest, and I think every time his work is shown, that happens again’, they replied, exchanging Mendieta’s name for a gendered and racial description of her body at death.

‘Oi Tate, we’ve got a vendetta,’ the crowd shouted, banging on the glass windows at the private view, ‘where the fuck is Ana Mendieta?’ One of the ironies of this history: if protesters have taken up the mantle of ensuring Mendieta’s work is not forgotten, with regard to the market and institutional representation, it’s not clear that they needed to. ‘Ana Mendieta suffered during life from being undervalued, not after her death,’ Coco Fusco wrote to me. ‘She has become a kind of postmodern Frida Kahlo. She has not been overlooked at all – on the contrary, she is one of the few Latin American women artists of her era who is widely known and exhibited.’ Her work is included in 57 public collections, in the US, Latin America, Europe and Australia, collections that include the Guggenheim and Tate, the same institutions where protests decrying her absence have been held. When Mendieta died, she was yet to have a single museum show.

The death of a beautiful woman, wrote Edgar Allan Poe, ‘is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world’, a sentiment shared by artists from John Everett Millais to David Lynch. The spectacle of female death has long been a defining cultural feature, and Mendieta’s posthumous CV may reveal an uncomfortable truth. In an artworld willing to congratulate itself for championing overlooked and maligned women, we must also acknowledge – as curators, viewers, writers, collectors, dealers and protesters – the possibility that we may be complicit in a collective type of abuse, in which the ideal woman artist is dead or close to dying. How to remember Mendieta, without viewing her practice solely through the lens of her death? How to mourn her without objectifying her? ‘Feminism is not served by turning violence into a litany’, writes Jacqueline Rose in ‘Feminism and the Abomination of Violence’ (2016). ‘Such strategy does not help us to think… violence against women is a crime of the deepest thoughtlessness. It is a sign that the mind has brutally blocked itself.’ In response, Rose urges us to think. Think enough, to disentangle the cultural fascination with female victimhood from the fight against misogyny. Think enough, so that we do not only see women as broken and damaged, even as we cannot ignore the breaking and damaging done. Think enough, so that any violence done to Mendieta does not brutally block our ability to see her work for what it was. Occasionally sadistic, mesmerisingly narcissistic, deeply ambitious and utterly beguiling.

Rosanna Mclaughlin is a writer and editor. In 2017 she was a TAARE resident with the British Council Caribbean

Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta runs at the Gropius Bau, Berlin, through 22 July 2018; Mendieta’s work is also currently on view in Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, at Brooklyn Museum, New York

From the April 2018 issue of ArtReview